FGV

Exibindo questões de 101 a 200.

Um quadrado de dimensões microscópicas tem área igual a 1,6 - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Um quadrado de dimensões microscópicas tem área igual a 1,6 × 10–10 m2. Sendo log 2 = m e log 5 = n, a medida do lado desse quadrado, em metro,

As bandeiras dos cinco países do Mercosul serão hasteadas - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020As bandeiras dos cinco países do Mercosul serão hasteadas em dois postes, um verde e um amarelo. As cinco bandeiras devem ser hasteadas e cada poste deve ter pelo menos uma bandeira. Constituem situações diferentes de hasteamento a troca de ordem das bandeiras em um mesmo poste e a troca das cores dos mastros associadas a cada configuração.

Ana, Bia, Cléo, Dani, Érica e Fabi se sentam ao redor de um - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Ana, Bia, Cléo, Dani, Érica e Fabi se sentam ao redor de uma mesa circular, como se estivessem nos vértices de um hexágono regular inscrito na circunferência da mesa. A respeito de suas posições, sabe-se que:

• Bia está imediatamente ao lado de Cléo e diametralmente oposta a Ana;

• Dani não está sentada imediatamente ao lado de Ana.

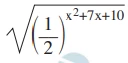

Sendo x um número real, o operador é igual a . Esse operado - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Sendo x um número real, o operador X é igual a Esse operador também admite composições como, por exemplo, -1 = 5. De acordo com a definição do operador, o valor de

Esse operador também admite composições como, por exemplo, -1 = 5. De acordo com a definição do operador, o valor de

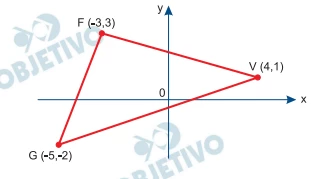

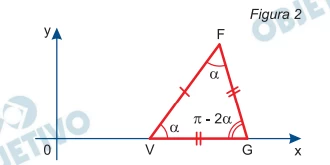

A figura indica o triângulo FGV, no plano cartesiano de - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020A figura indica o triângulo FGV, no plano cartesiano de eixos ortogonais, e as coordenadas dos seus vértices.

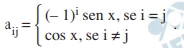

Considere a matriz quadrada A = (aij)2×2, com aij = . Sendo - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Considere a matriz quadrada A = (aij)2×2, com

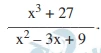

A soma das duas raízes não reais da equação algébrica x3 + - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020A soma das duas raízes não reais da equação algébrica x3 + 2x2 + 3x + 2 = 0, resolvida em C,

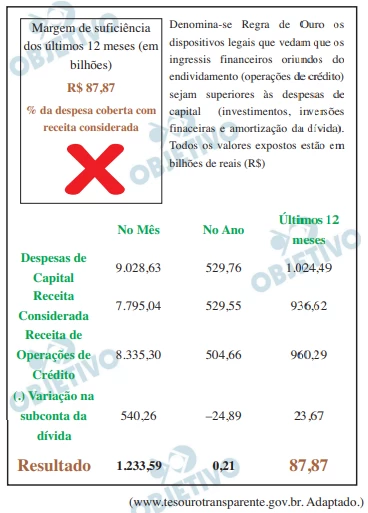

Admita que uma notícia, consultada na internet, tenha vindo - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Admita que uma notícia, consultada na internet, tenha vindo com um X no lugar de um gráfico, como indica a imagem a seguir

Sendo m e n números reais não nulos, um dos fatores do - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Sendo m e n números reais não nulos, um dos fatores do polinômio P(x) = mx2 – nx + m é (3x – 2).

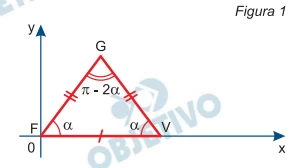

Seja FGV um triângulo isósceles, desenhado no plano - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Seja FGV um triângulo isósceles, desenhado no plano cartesiano de eixos ortogonais, com FG = GV = 5 e FV = 6, vértice F coincidindo com a origem dos eixos, FV contido no eixo x e ângulos internos, em radianos, como mostra a figura 1.

Uma urna contém 11 fichas idênticas, marcadas com os número - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Uma urna contém 11 fichas idênticas, marcadas com os números 2, 2, 3, 4, 5, 5, 5, 6, 7, 8 e 9. Retiram-se ao acaso duas fichas e denota-se o produto dos números obtidos por P. Em seguida, sem reposição, retira-se ao acaso mais uma ficha e denota-se o número obtido por N.

O valor máximo da função real dada por é igual a a) –2 - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020O valor máximo da função real dada por

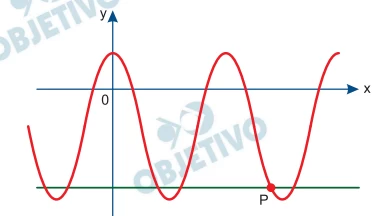

A figura indica os gráficos das funções reais definidas por - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020A figura indica os gráficos das funções reais definidas por y = –1 + 2cos (2x) e y + 1 + √3 = 0 no plano cartesiano de eixos ortogonais, sendo P um dos pontos de intersecção dos gráficos.

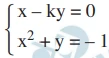

Sendo k um número real, o conjunto de todos os valores - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Sendo k um número real, o conjunto de todos os valores reais de k para os quais o sistema de equações

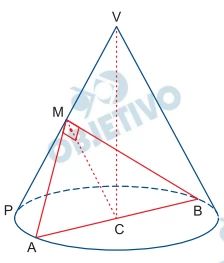

A figura indica um cone reto de revolução de vértice V, - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020A figura indica um cone reto de revolução de vértice V, altura VC e diâmetro da base AB. O ponto M pertence à geratriz VP do cone, AMB é um triângulo de área igual a 3√3 cm2, VC = BM, CM = CA = CB = MV = MP e o ângulo A ^ MB é reto.

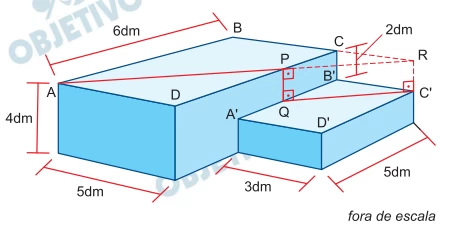

ABCD e A'B'C'D' são faces de dois paralelepípedos - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020ABCD e A'B'C'D' são faces de dois paralelepípedos retoretangulares que estão encostados de forma que duas arestas do menor estão totalmente contidas em duas arestas do maior, como mostra a figura. Além das medidas indicadas na figura, sabe-se que:

Além das medidas indicadas na figura, sabe-se que:

• P e Q pertencem a CD e A’B’, respectivamente;

• PQ é perpendicular a A’B’;

• RCB’C’ e RPQC’ são retângulos.

Em certo dia, a cotação da libra esterlina em Nova Iorque - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Em certo dia, a cotação da libra esterlina em Nova Iorque era de 1,25 dólar americano por 1,00 libra, e a cotação de 1,00 dólar americano era de 4,10 reais. Nesse mesmo dia, em Londres, 1,00 libra era cotada a 5,09 reais e 1 dólar americano era cotado a 4,15 reais. Bianca e Carolina compraram, nesse mesmo dia, 415 libras cada uma.

Com a finalidade de fazer uma reserva financeira para usar - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Com a finalidade de fazer uma reserva financeira para usar daqui a 10 anos, Luís planejou o seguinte investimento: depositar no mês 1 a quantia de R$ 500,00 e, em cada mês subsequente, depositar uma quantia 0,4% superior ao depósito do mês anterior, em uma aplicação financeira que rende 0,5% ao mês, capitalizado mensalmente.

Para que o preço atual de um produto ficasse igual ao preço - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Para que o preço atual de um produto ficasse igual ao preço dele 5 anos atrás, seria necessário dar um desconto de 60%. Sabendo-se que a média entre o preço atual desse produto e o preço praticado há 5 anos é igual a R$ 168,00,

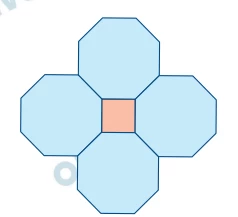

Um polígono regular de x lados está perfeitamente cercado - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Um polígono regular de x lados está perfeitamente cercado por polígonos regulares idênticos de y lados, sem sobreposições ou espaços livres. Por exemplo, a figura mostra a situação descrita para o caso em que x = 4 e y = 8.

Considere a equação 10z2 – 2iz – k = 0, em que z é um - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Considere a equação 10z2 – 2iz – k = 0, em que z é um número complexo e i2 = –1.

Uma moeda não honesta tem probabilidade igual a - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Uma moeda não honesta tem probabilidade igual a 2/3 de sair cara, contra 1/3 de sair coroa. Lançando-se essa moeda 20 vezes,

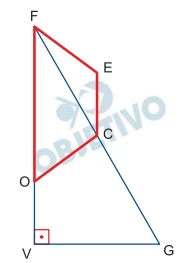

Na figura, FECO é um trapézio isósceles, com FE = OC = 5 cm - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Na figura, FECO é um trapézio isósceles, com FE = OC = 5 cm, EC = 4 cm e FO = 10 cm, e FGV é um triângulo retângulo com ângulo reto em V, com C em FG e O em FV.

Uma urna contém de bolas brancas e de bolas pretas, sendo - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Uma urna contém 2/3 de bolas brancas e 1/3 de bolas pretas, sendo que somente metade das bolas brancas e 2/3 das bolas pretas contêm um prêmio em seu interior. Uma bola dessa urna é sorteada aleatoriamente e, quando aberta, verifica-se que tem um prêmio no seu interior.

Uma amostra de cinco número inteiros não negativos, que - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Uma amostra de cinco número inteiros não negativos, que pode apresentar números repetidos, possui média igual a 10 e mediana igual a 12.

Atualmente, o preço de uma mercadoria é 20% superior ao que - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Atualmente, o preço de uma mercadoria é 20% superior ao que era há um ano. Sabe-se também que o preço atual é 10% superior ao preço da mercadoria na época em que ela custava R$ 100,00 a menos do que hoje.

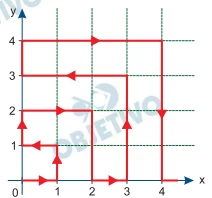

Uma formiga desloca-se sobre uma malha quadriculada com - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Uma formiga desloca-se sobre uma malha quadriculada com eixos cartesianos ortogonais. Ela parte do ponto de coordenadas (0, 0) e segue um caminho conforme o padrão indicado na figura.

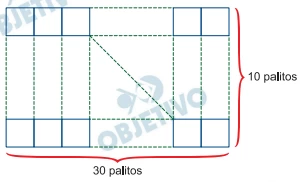

A figura indica uma configuração retangular feita com - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020A figura indica uma configuração retangular feita com palitos idênticos.

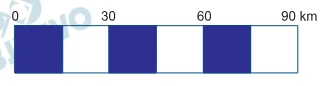

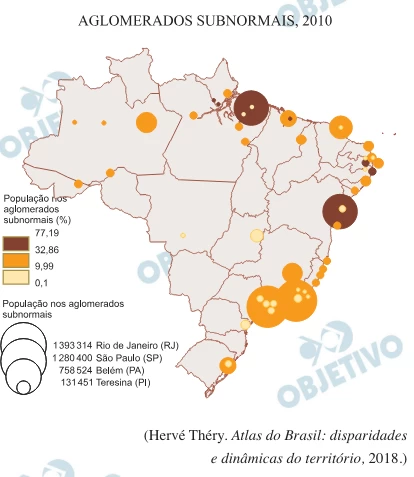

O planeta que está ficando cada vez mais desigual. Nos - FGV 2022

Geografia - 2020O planeta que está ficando cada vez mais desigual. Nos últimos 40 anos, a concentração de renda só cresceu com a globalização. Tanto é assim que atualmente nenhum país tem maior desigualdade que a África do Sul. O país, por ironia, viu crescer a desigualdade após o fim do Apartheid.

Na oração “— Traduzo coisa nenhuma” (5.o parágrafo), o term - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Modos de xingar

— Biltre!

— O quê?

— Biltre! Sacripanta!

— Traduz isso para português.

— Traduzo coisa nenhuma. Além do mais, charro!

Onagro!

Parei para escutar. As palavras estranhas jorravam do interior de um Ford de bigode. Quem as proferia era um senhor idoso, terno escuro, fisionomia respeitável, alterada pela indignação. Quem as recebia era um garotão de camisa esporte; dentes clarinhos emergindo da floresta capilar, no interior de um fusca. Desses casos de toda hora: o fusca bateu no Ford. Discussão. Bate-boca. O velho usava o repertório de xingamentos de seu tempo e de sua condição: professor, quem sabe? leitor de Camilo Castelo Branco.

Os velhos xingamentos. Pessoas havia que se recusavam a usar o trivial das ruas e botequins, e iam pedir a Rui Barbosa, aos mestres da língua, expressões que castigassem fortemente o adversário. Esse material seleto vinha esmaltar artigos de polêmica (polemizava-se muito nos jornais do começo do século), discursos políticos (nos intervalos do estado de sítio, é lógico) e um pouco os incidentes de calçada. A maioria, sem dúvida, não se empenhava em requintes.

(Carlos Drummond de Andrade. “Modos de xingar”.

As palavras que ninguém diz, 2011.)

A frase do último parágrafo do texto “A maioria, sem dúvida - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Modos de xingar

— Biltre!

— O quê?

— Biltre! Sacripanta!

— Traduz isso para português.

— Traduzo coisa nenhuma. Além do mais, charro!

Onagro!

Parei para escutar. As palavras estranhas jorravam do interior de um Ford de bigode. Quem as proferia era um senhor idoso, terno escuro, fisionomia respeitável, alterada pela indignação. Quem as recebia era um garotão de camisa esporte; dentes clarinhos emergindo da floresta capilar, no interior de um fusca. Desses casos de toda hora: o fusca bateu no Ford. Discussão. Bate-boca. O velho usava o repertório de xingamentos de seu tempo e de sua condição: professor, quem sabe? leitor de Camilo Castelo Branco.

Os velhos xingamentos. Pessoas havia que se recusavam a usar o trivial das ruas e botequins, e iam pedir a Rui Barbosa, aos mestres da língua, expressões que castigassem fortemente o adversário. Esse material seleto vinha esmaltar artigos de polêmica (polemizava-se muito nos jornais do começo do século), discursos políticos (nos intervalos do estado de sítio, é lógico) e um pouco os incidentes de calçada. A maioria, sem dúvida, não se empenhava em requintes.

(Carlos Drummond de Andrade. “Modos de xingar”.

As palavras que ninguém diz, 2011.)

Analisando-se os modos de organização do texto, conclui-se - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Modos de xingar

— Biltre!

— O quê?

— Biltre! Sacripanta!

— Traduz isso para português.

— Traduzo coisa nenhuma. Além do mais, charro!

Onagro!

Parei para escutar. As palavras estranhas jorravam do interior de um Ford de bigode. Quem as proferia era um senhor idoso, terno escuro, fisionomia respeitável, alterada pela indignação. Quem as recebia era um garotão de camisa esporte; dentes clarinhos emergindo da floresta capilar, no interior de um fusca. Desses casos de toda hora: o fusca bateu no Ford. Discussão. Bate-boca. O velho usava o repertório de xingamentos de seu tempo e de sua condição: professor, quem sabe? leitor de Camilo Castelo Branco.

Os velhos xingamentos. Pessoas havia que se recusavam a usar o trivial das ruas e botequins, e iam pedir a Rui Barbosa, aos mestres da língua, expressões que castigassem fortemente o adversário. Esse material seleto vinha esmaltar artigos de polêmica (polemizava-se muito nos jornais do começo do século), discursos políticos (nos intervalos do estado de sítio, é lógico) e um pouco os incidentes de calçada. A maioria, sem dúvida, não se empenhava em requintes.

(Carlos Drummond de Andrade. “Modos de xingar”.

As palavras que ninguém diz, 2011.)

As passagens “— O quê?” (2.o parágrafo) e “professor, quem - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Modos de xingar

— Biltre!

— O quê?

— Biltre! Sacripanta!

— Traduz isso para português.

— Traduzo coisa nenhuma. Além do mais, charro!

Onagro!

Parei para escutar. As palavras estranhas jorravam do interior de um Ford de bigode. Quem as proferia era um senhor idoso, terno escuro, fisionomia respeitável, alterada pela indignação. Quem as recebia era um garotão de camisa esporte; dentes clarinhos emergindo da floresta capilar, no interior de um fusca. Desses casos de toda hora: o fusca bateu no Ford. Discussão. Bate-boca. O velho usava o repertório de xingamentos de seu tempo e de sua condição: professor, quem sabe? leitor de Camilo Castelo Branco.

Os velhos xingamentos. Pessoas havia que se recusavam a usar o trivial das ruas e botequins, e iam pedir a Rui Barbosa, aos mestres da língua, expressões que castigassem fortemente o adversário. Esse material seleto vinha esmaltar artigos de polêmica (polemizava-se muito nos jornais do começo do século), discursos políticos (nos intervalos do estado de sítio, é lógico) e um pouco os incidentes de calçada. A maioria, sem dúvida, não se empenhava em requintes.

(Carlos Drummond de Andrade. “Modos de xingar”.

As palavras que ninguém diz, 2011.)

Nas frases “E outra que ele come para digerir de novo” e “ - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia a tira Níquel Náusea, de Fernando Gonsales.

Nas expressões “cientistas exasperados”, “exemplar da - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Nos dois primeiros episódios da série Chernobyl, da HBO, cientistas exasperados tentam convencer os superiores na usina e no governo soviético de que um dos reatores nucleares explodiu e está jorrando radioatividade sobre a Europa.

A resposta dos superiores, exemplar da estupidez surrealista de uma burocracia totalitária, é sempre a mesma: impossível, um “reator RBMK não explode”. A posição oficial é que havia somente um pequeno incêndio no telhado.

“Eu fui lá, eu vi!”, repetem os cientistas, um após o outro, antes de vomitarem, verterem sangue pelos poros ou caírem duros. Apenas quando a radioatividade é detectada na Suécia, Mikhail Gorbatchov encara seus ministros com uma expressão de “camarada, deu ruim...” — naquela altura, a radioatividade liberada já era superior à de vinte bombas de Hiroshima.

Só mesmo no totalitarismo soviético, pensei, assistindo à série. Então fui ler na revista Piauí o trecho do livro A Terra inabitável: uma história do futuro, do jornalista David Wallace-Wells, que sairá pela Companhia das Letras no mês que vem. Impossível terminar as 11 páginas sobre o aquecimento global sem ficar apavorado feito um cientista em Chernobyl.

(Antonio Prata. “Bem-vindos a Chernobyl”.

www.folha.uol.com.br, 16.06.2019. Adaptado.)

Considere as passagens do texto: • [...] impossível, um - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Nos dois primeiros episódios da série Chernobyl, da HBO, cientistas exasperados tentam convencer os superiores na usina e no governo soviético de que um dos reatores nucleares explodiu e está jorrando radioatividade sobre a Europa.

A resposta dos superiores, exemplar da estupidez surrealista de uma burocracia totalitária, é sempre a mesma: impossível, um “reator RBMK não explode”. A posição oficial é que havia somente um pequeno incêndio no telhado.

“Eu fui lá, eu vi!”, repetem os cientistas, um após o outro, antes de vomitarem, verterem sangue pelos poros ou caírem duros. Apenas quando a radioatividade é detectada na Suécia, Mikhail Gorbatchov encara seus ministros com uma expressão de “camarada, deu ruim...” — naquela altura, a radioatividade liberada já era superior à de vinte bombas de Hiroshima.

Só mesmo no totalitarismo soviético, pensei, assistindo à série. Então fui ler na revista Piauí o trecho do livro A Terra inabitável: uma história do futuro, do jornalista David Wallace-Wells, que sairá pela Companhia das Letras no mês que vem. Impossível terminar as 11 páginas sobre o aquecimento global sem ficar apavorado feito um cientista em Chernobyl.

(Antonio Prata. “Bem-vindos a Chernobyl”.

www.folha.uol.com.br, 16.06.2019. Adaptado.)

No texto, a variedade formal da língua, flagrada na - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Nos dois primeiros episódios da série Chernobyl, da HBO, cientistas exasperados tentam convencer os superiores na usina e no governo soviético de que um dos reatores nucleares explodiu e está jorrando radioatividade sobre a Europa.

A resposta dos superiores, exemplar da estupidez surrealista de uma burocracia totalitária, é sempre a mesma: impossível, um “reator RBMK não explode”. A posição oficial é que havia somente um pequeno incêndio no telhado.

“Eu fui lá, eu vi!”, repetem os cientistas, um após o outro, antes de vomitarem, verterem sangue pelos poros ou caírem duros. Apenas quando a radioatividade é detectada na Suécia, Mikhail Gorbatchov encara seus ministros com uma expressão de “camarada, deu ruim...” — naquela altura, a radioatividade liberada já era superior à de vinte bombas de Hiroshima.

Só mesmo no totalitarismo soviético, pensei, assistindo à série. Então fui ler na revista Piauí o trecho do livro A Terra inabitável: uma história do futuro, do jornalista David Wallace-Wells, que sairá pela Companhia das Letras no mês que vem. Impossível terminar as 11 páginas sobre o aquecimento global sem ficar apavorado feito um cientista em Chernobyl.

(Antonio Prata. “Bem-vindos a Chernobyl”.

www.folha.uol.com.br, 16.06.2019. Adaptado.)

Nas passagens do texto da Exame “focos de incêndio floresta - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia um trecho da letra da canção “Amazônia”, de Roberto Carlos, para responder

Amazônia

A lei do machado

Avalanches de desatinos

Numa ambição desmedida

Absurdos contra os destinos

De tantas fontes de vida

Quanta falta de juízo

Tolices fatais

Quem desmata, mata

Não sabe o que faz

Como dormir e sonhar

Quando a fumaça no ar

Arde nos olhos de quem pode ver

Terríveis sinais, de alerta, desperta

Pra selva viver

Amazônia, insônia do mundo

Amazônia, insônia do mundo

(www.vagalume.com.br)

Os versos “Avalanches de desatinos / Numa ambição desmedida - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia um trecho da letra da canção “Amazônia”, de Roberto Carlos, para responder

Amazônia

A lei do machado

Avalanches de desatinos

Numa ambição desmedida

Absurdos contra os destinos

De tantas fontes de vida

Quanta falta de juízo

Tolices fatais

Quem desmata, mata

Não sabe o que faz

Como dormir e sonhar

Quando a fumaça no ar

Arde nos olhos de quem pode ver

Terríveis sinais, de alerta, desperta

Pra selva viver

Amazônia, insônia do mundo

Amazônia, insônia do mundo

(www.vagalume.com.br)

No período do quarto parágrafo “O que causa estranheza aos - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

São Paulo – Os olhos do Brasil e do mundo se voltam para a maior floresta tropical e maior reserva de biodiversidade da Terra. Milhares de mensagens de alerta em diferentes línguas circulam nas redes sociais com a hashtag #PrayForAmazonia. A razão não poderia ser pior: a Amazônia arde em chamas.

O bioma é o mais afetado pela maior onda de incêndios florestais no Brasil em sete anos. Não há novidade no fenômeno em si. A Amazônia sempre sofreu com queimadas ligadas à exploração de terra. Mas como isso chegou tão longe? Segundo dados do Inpe, o número de focos de incêndio florestal aumentou 83% entre janeiro e agosto de 2019 na comparação com o mesmo período de 2018. Desde 1.o de janeiro até a terça-feira [20.08.2019] foram contabilizados 74 155 focos, alta de 84% em relação ao mesmo período do ano passado. É o número mais alto desde que os registros começaram, em 2013. A última grande onda é de 2016, com 66 622 focos de queimadas nesse período. Combinado a períodos de seca severa, o desmatamento e a prática de queimadas podem gerar um saldo final incendiário. O que causa estranheza aos especialistas nos eventos de 2019, porém, é que a seca não se mostra tão severa como nos anos anteriores e tampouco houve eventos climáticos extremos, como o El Niño, que justifiquem um aumento considerável nos focos de incêndio. Além disso, os tempos de seca mais severos ocorrem geralmente no mês de setembro. Ou seja: a mão do homem pesou, e muito, para a alta neste ano.

(Vanessa Barbosa. “Inferno na floresta: o que sabemos sobre os

incêndios na Amazônia”. https://exame.abril.com.br, 23.08.2019.

Adaptado.)

Assinale a alternativa que atende à norma-padrão de - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

São Paulo – Os olhos do Brasil e do mundo se voltam para a maior floresta tropical e maior reserva de biodiversidade da Terra. Milhares de mensagens de alerta em diferentes línguas circulam nas redes sociais com a hashtag #PrayForAmazonia. A razão não poderia ser pior: a Amazônia arde em chamas.

O bioma é o mais afetado pela maior onda de incêndios florestais no Brasil em sete anos. Não há novidade no fenômeno em si. A Amazônia sempre sofreu com queimadas ligadas à exploração de terra. Mas como isso chegou tão longe? Segundo dados do Inpe, o número de focos de incêndio florestal aumentou 83% entre janeiro e agosto de 2019 na comparação com o mesmo período de 2018. Desde 1.o de janeiro até a terça-feira [20.08.2019] foram contabilizados 74 155 focos, alta de 84% em relação ao mesmo período do ano passado. É o número mais alto desde que os registros começaram, em 2013. A última grande onda é de 2016, com 66 622 focos de queimadas nesse período. Combinado a períodos de seca severa, o desmatamento e a prática de queimadas podem gerar um saldo final incendiário. O que causa estranheza aos especialistas nos eventos de 2019, porém, é que a seca não se mostra tão severa como nos anos anteriores e tampouco houve eventos climáticos extremos, como o El Niño, que justifiquem um aumento considerável nos focos de incêndio. Além disso, os tempos de seca mais severos ocorrem geralmente no mês de setembro. Ou seja: a mão do homem pesou, e muito, para a alta neste ano.

(Vanessa Barbosa. “Inferno na floresta: o que sabemos sobre os

incêndios na Amazônia”. https://exame.abril.com.br, 23.08.2019.

Adaptado.)

De acordo com o Dicionário Houaiss, a metonímia é uma - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

São Paulo – Os olhos do Brasil e do mundo se voltam para a maior floresta tropical e maior reserva de biodiversidade da Terra. Milhares de mensagens de alerta em diferentes línguas circulam nas redes sociais com a hashtag #PrayForAmazonia. A razão não poderia ser pior: a Amazônia arde em chamas.

O bioma é o mais afetado pela maior onda de incêndios florestais no Brasil em sete anos. Não há novidade no fenômeno em si. A Amazônia sempre sofreu com queimadas ligadas à exploração de terra. Mas como isso chegou tão longe? Segundo dados do Inpe, o número de focos de incêndio florestal aumentou 83% entre janeiro e agosto de 2019 na comparação com o mesmo período de 2018. Desde 1.o de janeiro até a terça-feira [20.08.2019] foram contabilizados 74 155 focos, alta de 84% em relação ao mesmo período do ano passado. É o número mais alto desde que os registros começaram, em 2013. A última grande onda é de 2016, com 66 622 focos de queimadas nesse período. Combinado a períodos de seca severa, o desmatamento e a prática de queimadas podem gerar um saldo final incendiário. O que causa estranheza aos especialistas nos eventos de 2019, porém, é que a seca não se mostra tão severa como nos anos anteriores e tampouco houve eventos climáticos extremos, como o El Niño, que justifiquem um aumento considerável nos focos de incêndio. Além disso, os tempos de seca mais severos ocorrem geralmente no mês de setembro. Ou seja: a mão do homem pesou, e muito, para a alta neste ano.

(Vanessa Barbosa. “Inferno na floresta: o que sabemos sobre os

incêndios na Amazônia”. https://exame.abril.com.br, 23.08.2019.

Adaptado.)

Na organização das informações textuais, as expressões - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Na organização das informações textuais, as expressões sublinhadas em “ A razão não poderia ser pior: a Amazônia arde em chamas” (1.o parágrafo) e “Ou seja: a mão do homem pesou, e muito, para a alta neste ano” (4.o parágrafo) têm, respectivamente, a função de:

As informações do texto permitem concluir que a) a - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

São Paulo – Os olhos do Brasil e do mundo se voltam para a maior floresta tropical e maior reserva de biodiversidade da Terra. Milhares de mensagens de alerta em diferentes línguas circulam nas redes sociais com a hashtag #PrayForAmazonia. A razão não poderia ser pior: a Amazônia arde em chamas.

O bioma é o mais afetado pela maior onda de incêndios florestais no Brasil em sete anos. Não há novidade no fenômeno em si. A Amazônia sempre sofreu com queimadas ligadas à exploração de terra. Mas como isso chegou tão longe? Segundo dados do Inpe, o número de focos de incêndio florestal aumentou 83% entre janeiro e agosto de 2019 na comparação com o mesmo período de 2018. Desde 1.o de janeiro até a terça-feira [20.08.2019] foram contabilizados 74 155 focos, alta de 84% em relação ao mesmo período do ano passado. É o número mais alto desde que os registros começaram, em 2013. A última grande onda é de 2016, com 66 622 focos de queimadas nesse período. Combinado a períodos de seca severa, o desmatamento e a prática de queimadas podem gerar um saldo final incendiário. O que causa estranheza aos especialistas nos eventos de 2019, porém, é que a seca não se mostra tão severa como nos anos anteriores e tampouco houve eventos climáticos extremos, como o El Niño, que justifiquem um aumento considerável nos focos de incêndio. Além disso, os tempos de seca mais severos ocorrem geralmente no mês de setembro. Ou seja: a mão do homem pesou, e muito, para a alta neste ano.

(Vanessa Barbosa. “Inferno na floresta: o que sabemos sobre os

incêndios na Amazônia”. https://exame.abril.com.br, 23.08.2019.

Adaptado.)

According to the fourth subitem “Effectiveness and elegance - FGV 2020

Inglês - 2020Read the text

There’s something faintly embarrassing about the 50th anniversary of the first moonwalk. It was just so long ago. It’s no longer “we” who put a man on the moon, it’s “they” who put a man on the moon. So why can’t “we” do it? It’s hard not to feel that for all the technological advances of the last halfcentury, America has lost something — the ability to unite and overcome long odds to achieve greatness.

At one level, this is silly. The U.S. stopped going to the moon because Americans stopped seeing the point of it, not because they stopped being capable of it. Still, the historic Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs do have something to teach us. Months before the moon landing, the journal Science wrote that the space program’s “most valuable spin-off of all will be human rather than technological: better knowledge of how to plan, coordinate and monitor the multitudinous and varied activities of the organizations required to accomplish great social undertakings.” So, here, lessons the Apollo has left behind.

1. _____________ President John Kennedy simplified NASA’s job with his 1961 address to Congress committing to “the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” From then on, any decision was made by whether it would aid or impede the agency in meeting that deadline. Experiments that were too heavy were shelved, however valuable they might have been. Technologies that were superior but not ready for deployment were set aside. Having a North Star to pursue was essential, because skeptics and critics abounded. Amid protests over the Vietnam war and race riots, NASA engineers kept their heads down and their slide rules busy.

2. Harness incongruence. In any large organization there is pressure to suppress dissent. That can be deadly, as it was for NASA in the two space shuttle failures — Challenger and Columbia — each of which killed all seven crew members. Leading up to both tragedies, the fact that engineers grew concerned about a technical problem they did not fully understand, but they could not make a quantitative case; and were consequently ignored.

After the bad years of the shuttle disasters, the practice of harnessing incongruence, and learning from mistakes, has staged something of a revival at NASA, which has since successfully sent unmanned craft to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Says Adam Stelzner, a NASA engineer, “Listen to all that the problem has to say, do not make assumptions or commit to a plan of action based on them until the deepest truth presents itself ”.

3. Delegate but decide. NASA realized early on that it needed help. About 90% of Apollo’s budget was spent on contractors from the most varied places. NASA itself was, therefore, more of a confederation than a single agency.

With so many players involved, turf wars were unavoidable. NASA Administrator James Webb coined the phrase Space Age Management to describe how he tried to manage conflicts and ensure final decisions were made by headquarters. Unfortunately, Webb’s mastery of the complex network was not as thorough as he believed. The death of three astronauts during a routine test in 1967 was traced to deficiencies Webb had been unaware of. Failure, in this case, was as instructive as success.

4. Effectiveness and elegance. Aesthetically, the Apollo mission was poor. The module that touched down on the moon looked like an oversize version of a kid’s cardboard science project, all right angles and skinny legs. Apollo’s return to Earth was equally unglamorous. The spaceship that left the launch pad was awesome; what was, by plan, to be rescued from the Pacific Ocean was a stubby cone weighing just 0.2% of the majestic original. But what looks clunky and awkward to an outsider may appear elegant to an engineer. Engineering inelegance, by contrast, would be redesigning a machine without fully anticipating the consequences.

Most of the people alive today had not yet arrived on the planet when Armstrong, Aldrin and Commander Michael Collins returned to it after their historic voyage. Never mind, though. The moon landing was a victory for all of the human race, past, present, and future.

(Peter Coy. Bloomberg Businessweek, 22.07.2019. Adapted.)

In the fragment from the seventh paragraph “Webb’s mastery - FGV 2020

Inglês - 2020Read the text

There’s something faintly embarrassing about the 50th anniversary of the first moonwalk. It was just so long ago. It’s no longer “we” who put a man on the moon, it’s “they” who put a man on the moon. So why can’t “we” do it? It’s hard not to feel that for all the technological advances of the last halfcentury, America has lost something — the ability to unite and overcome long odds to achieve greatness.

At one level, this is silly. The U.S. stopped going to the moon because Americans stopped seeing the point of it, not because they stopped being capable of it. Still, the historic Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs do have something to teach us. Months before the moon landing, the journal Science wrote that the space program’s “most valuable spin-off of all will be human rather than technological: better knowledge of how to plan, coordinate and monitor the multitudinous and varied activities of the organizations required to accomplish great social undertakings.” So, here, lessons the Apollo has left behind.

1. _____________ President John Kennedy simplified NASA’s job with his 1961 address to Congress committing to “the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” From then on, any decision was made by whether it would aid or impede the agency in meeting that deadline. Experiments that were too heavy were shelved, however valuable they might have been. Technologies that were superior but not ready for deployment were set aside. Having a North Star to pursue was essential, because skeptics and critics abounded. Amid protests over the Vietnam war and race riots, NASA engineers kept their heads down and their slide rules busy.

2. Harness incongruence. In any large organization there is pressure to suppress dissent. That can be deadly, as it was for NASA in the two space shuttle failures — Challenger and Columbia — each of which killed all seven crew members. Leading up to both tragedies, the fact that engineers grew concerned about a technical problem they did not fully understand, but they could not make a quantitative case; and were consequently ignored.

After the bad years of the shuttle disasters, the practice of harnessing incongruence, and learning from mistakes, has staged something of a revival at NASA, which has since successfully sent unmanned craft to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Says Adam Stelzner, a NASA engineer, “Listen to all that the problem has to say, do not make assumptions or commit to a plan of action based on them until the deepest truth presents itself ”.

3. Delegate but decide. NASA realized early on that it needed help. About 90% of Apollo’s budget was spent on contractors from the most varied places. NASA itself was, therefore, more of a confederation than a single agency.

With so many players involved, turf wars were unavoidable. NASA Administrator James Webb coined the phrase Space Age Management to describe how he tried to manage conflicts and ensure final decisions were made by headquarters. Unfortunately, Webb’s mastery of the complex network was not as thorough as he believed. The death of three astronauts during a routine test in 1967 was traced to deficiencies Webb had been unaware of. Failure, in this case, was as instructive as success.

4. Effectiveness and elegance. Aesthetically, the Apollo mission was poor. The module that touched down on the moon looked like an oversize version of a kid’s cardboard science project, all right angles and skinny legs. Apollo’s return to Earth was equally unglamorous. The spaceship that left the launch pad was awesome; what was, by plan, to be rescued from the Pacific Ocean was a stubby cone weighing just 0.2% of the majestic original. But what looks clunky and awkward to an outsider may appear elegant to an engineer. Engineering inelegance, by contrast, would be redesigning a machine without fully anticipating the consequences.

Most of the people alive today had not yet arrived on the planet when Armstrong, Aldrin and Commander Michael Collins returned to it after their historic voyage. Never mind, though. The moon landing was a victory for all of the human race, past, present, and future.

(Peter Coy. Bloomberg Businessweek, 22.07.2019. Adapted.)

In the specific context of subitem 3 “Delegate but decide”, - FGV 2020

Inglês - 2020Read the text

There’s something faintly embarrassing about the 50th anniversary of the first moonwalk. It was just so long ago. It’s no longer “we” who put a man on the moon, it’s “they” who put a man on the moon. So why can’t “we” do it? It’s hard not to feel that for all the technological advances of the last halfcentury, America has lost something — the ability to unite and overcome long odds to achieve greatness.

At one level, this is silly. The U.S. stopped going to the moon because Americans stopped seeing the point of it, not because they stopped being capable of it. Still, the historic Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs do have something to teach us. Months before the moon landing, the journal Science wrote that the space program’s “most valuable spin-off of all will be human rather than technological: better knowledge of how to plan, coordinate and monitor the multitudinous and varied activities of the organizations required to accomplish great social undertakings.” So, here, lessons the Apollo has left behind.

1. _____________ President John Kennedy simplified NASA’s job with his 1961 address to Congress committing to “the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” From then on, any decision was made by whether it would aid or impede the agency in meeting that deadline. Experiments that were too heavy were shelved, however valuable they might have been. Technologies that were superior but not ready for deployment were set aside. Having a North Star to pursue was essential, because skeptics and critics abounded. Amid protests over the Vietnam war and race riots, NASA engineers kept their heads down and their slide rules busy.

2. Harness incongruence. In any large organization there is pressure to suppress dissent. That can be deadly, as it was for NASA in the two space shuttle failures — Challenger and Columbia — each of which killed all seven crew members. Leading up to both tragedies, the fact that engineers grew concerned about a technical problem they did not fully understand, but they could not make a quantitative case; and were consequently ignored.

After the bad years of the shuttle disasters, the practice of harnessing incongruence, and learning from mistakes, has staged something of a revival at NASA, which has since successfully sent unmanned craft to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Says Adam Stelzner, a NASA engineer, “Listen to all that the problem has to say, do not make assumptions or commit to a plan of action based on them until the deepest truth presents itself ”.

3. Delegate but decide. NASA realized early on that it needed help. About 90% of Apollo’s budget was spent on contractors from the most varied places. NASA itself was, therefore, more of a confederation than a single agency.

With so many players involved, turf wars were unavoidable. NASA Administrator James Webb coined the phrase Space Age Management to describe how he tried to manage conflicts and ensure final decisions were made by headquarters. Unfortunately, Webb’s mastery of the complex network was not as thorough as he believed. The death of three astronauts during a routine test in 1967 was traced to deficiencies Webb had been unaware of. Failure, in this case, was as instructive as success.

4. Effectiveness and elegance. Aesthetically, the Apollo mission was poor. The module that touched down on the moon looked like an oversize version of a kid’s cardboard science project, all right angles and skinny legs. Apollo’s return to Earth was equally unglamorous. The spaceship that left the launch pad was awesome; what was, by plan, to be rescued from the Pacific Ocean was a stubby cone weighing just 0.2% of the majestic original. But what looks clunky and awkward to an outsider may appear elegant to an engineer. Engineering inelegance, by contrast, would be redesigning a machine without fully anticipating the consequences.

Most of the people alive today had not yet arrived on the planet when Armstrong, Aldrin and Commander Michael Collins returned to it after their historic voyage. Never mind, though. The moon landing was a victory for all of the human race, past, present, and future.

(Peter Coy. Bloomberg Businessweek, 22.07.2019. Adapted.)

In the fragment from the sixth paragraph “NASA itself was, - FGV 2020

Inglês - 2020Read the text

There’s something faintly embarrassing about the 50th anniversary of the first moonwalk. It was just so long ago. It’s no longer “we” who put a man on the moon, it’s “they” who put a man on the moon. So why can’t “we” do it? It’s hard not to feel that for all the technological advances of the last halfcentury, America has lost something — the ability to unite and overcome long odds to achieve greatness.

At one level, this is silly. The U.S. stopped going to the moon because Americans stopped seeing the point of it, not because they stopped being capable of it. Still, the historic Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs do have something to teach us. Months before the moon landing, the journal Science wrote that the space program’s “most valuable spin-off of all will be human rather than technological: better knowledge of how to plan, coordinate and monitor the multitudinous and varied activities of the organizations required to accomplish great social undertakings.” So, here, lessons the Apollo has left behind.

1. _____________ President John Kennedy simplified NASA’s job with his 1961 address to Congress committing to “the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” From then on, any decision was made by whether it would aid or impede the agency in meeting that deadline. Experiments that were too heavy were shelved, however valuable they might have been. Technologies that were superior but not ready for deployment were set aside. Having a North Star to pursue was essential, because skeptics and critics abounded. Amid protests over the Vietnam war and race riots, NASA engineers kept their heads down and their slide rules busy.

2. Harness incongruence. In any large organization there is pressure to suppress dissent. That can be deadly, as it was for NASA in the two space shuttle failures — Challenger and Columbia — each of which killed all seven crew members. Leading up to both tragedies, the fact that engineers grew concerned about a technical problem they did not fully understand, but they could not make a quantitative case; and were consequently ignored.

After the bad years of the shuttle disasters, the practice of harnessing incongruence, and learning from mistakes, has staged something of a revival at NASA, which has since successfully sent unmanned craft to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Says Adam Stelzner, a NASA engineer, “Listen to all that the problem has to say, do not make assumptions or commit to a plan of action based on them until the deepest truth presents itself ”.

3. Delegate but decide. NASA realized early on that it needed help. About 90% of Apollo’s budget was spent on contractors from the most varied places. NASA itself was, therefore, more of a confederation than a single agency.

With so many players involved, turf wars were unavoidable. NASA Administrator James Webb coined the phrase Space Age Management to describe how he tried to manage conflicts and ensure final decisions were made by headquarters. Unfortunately, Webb’s mastery of the complex network was not as thorough as he believed. The death of three astronauts during a routine test in 1967 was traced to deficiencies Webb had been unaware of. Failure, in this case, was as instructive as success.

4. Effectiveness and elegance. Aesthetically, the Apollo mission was poor. The module that touched down on the moon looked like an oversize version of a kid’s cardboard science project, all right angles and skinny legs. Apollo’s return to Earth was equally unglamorous. The spaceship that left the launch pad was awesome; what was, by plan, to be rescued from the Pacific Ocean was a stubby cone weighing just 0.2% of the majestic original. But what looks clunky and awkward to an outsider may appear elegant to an engineer. Engineering inelegance, by contrast, would be redesigning a machine without fully anticipating the consequences.

Most of the people alive today had not yet arrived on the planet when Armstrong, Aldrin and Commander Michael Collins returned to it after their historic voyage. Never mind, though. The moon landing was a victory for all of the human race, past, present, and future.

(Peter Coy. Bloomberg Businessweek, 22.07.2019. Adapted.)

In the context of the fourth paragraph, the verb “harness” - FGV 2020

Inglês - 2020Read the text

There’s something faintly embarrassing about the 50th anniversary of the first moonwalk. It was just so long ago. It’s no longer “we” who put a man on the moon, it’s “they” who put a man on the moon. So why can’t “we” do it? It’s hard not to feel that for all the technological advances of the last halfcentury, America has lost something — the ability to unite and overcome long odds to achieve greatness.

At one level, this is silly. The U.S. stopped going to the moon because Americans stopped seeing the point of it, not because they stopped being capable of it. Still, the historic Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs do have something to teach us. Months before the moon landing, the journal Science wrote that the space program’s “most valuable spin-off of all will be human rather than technological: better knowledge of how to plan, coordinate and monitor the multitudinous and varied activities of the organizations required to accomplish great social undertakings.” So, here, lessons the Apollo has left behind.

1. _____________ President John Kennedy simplified NASA’s job with his 1961 address to Congress committing to “the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” From then on, any decision was made by whether it would aid or impede the agency in meeting that deadline. Experiments that were too heavy were shelved, however valuable they might have been. Technologies that were superior but not ready for deployment were set aside. Having a North Star to pursue was essential, because skeptics and critics abounded. Amid protests over the Vietnam war and race riots, NASA engineers kept their heads down and their slide rules busy.

2. Harness incongruence. In any large organization there is pressure to suppress dissent. That can be deadly, as it was for NASA in the two space shuttle failures — Challenger and Columbia — each of which killed all seven crew members. Leading up to both tragedies, the fact that engineers grew concerned about a technical problem they did not fully understand, but they could not make a quantitative case; and were consequently ignored.

After the bad years of the shuttle disasters, the practice of harnessing incongruence, and learning from mistakes, has staged something of a revival at NASA, which has since successfully sent unmanned craft to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Says Adam Stelzner, a NASA engineer, “Listen to all that the problem has to say, do not make assumptions or commit to a plan of action based on them until the deepest truth presents itself ”.

3. Delegate but decide. NASA realized early on that it needed help. About 90% of Apollo’s budget was spent on contractors from the most varied places. NASA itself was, therefore, more of a confederation than a single agency.

With so many players involved, turf wars were unavoidable. NASA Administrator James Webb coined the phrase Space Age Management to describe how he tried to manage conflicts and ensure final decisions were made by headquarters. Unfortunately, Webb’s mastery of the complex network was not as thorough as he believed. The death of three astronauts during a routine test in 1967 was traced to deficiencies Webb had been unaware of. Failure, in this case, was as instructive as success.

4. Effectiveness and elegance. Aesthetically, the Apollo mission was poor. The module that touched down on the moon looked like an oversize version of a kid’s cardboard science project, all right angles and skinny legs. Apollo’s return to Earth was equally unglamorous. The spaceship that left the launch pad was awesome; what was, by plan, to be rescued from the Pacific Ocean was a stubby cone weighing just 0.2% of the majestic original. But what looks clunky and awkward to an outsider may appear elegant to an engineer. Engineering inelegance, by contrast, would be redesigning a machine without fully anticipating the consequences.

Most of the people alive today had not yet arrived on the planet when Armstrong, Aldrin and Commander Michael Collins returned to it after their historic voyage. Never mind, though. The moon landing was a victory for all of the human race, past, present, and future.

(Peter Coy. Bloomberg Businessweek, 22.07.2019. Adapted.)

From the reading of subitem 2 “Harness incongruence”, we - FGV 2020

Inglês - 2020Read the text

There’s something faintly embarrassing about the 50th anniversary of the first moonwalk. It was just so long ago. It’s no longer “we” who put a man on the moon, it’s “they” who put a man on the moon. So why can’t “we” do it? It’s hard not to feel that for all the technological advances of the last halfcentury, America has lost something — the ability to unite and overcome long odds to achieve greatness.

At one level, this is silly. The U.S. stopped going to the moon because Americans stopped seeing the point of it, not because they stopped being capable of it. Still, the historic Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs do have something to teach us. Months before the moon landing, the journal Science wrote that the space program’s “most valuable spin-off of all will be human rather than technological: better knowledge of how to plan, coordinate and monitor the multitudinous and varied activities of the organizations required to accomplish great social undertakings.” So, here, lessons the Apollo has left behind.

1. _____________ President John Kennedy simplified NASA’s job with his 1961 address to Congress committing to “the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” From then on, any decision was made by whether it would aid or impede the agency in meeting that deadline. Experiments that were too heavy were shelved, however valuable they might have been. Technologies that were superior but not ready for deployment were set aside. Having a North Star to pursue was essential, because skeptics and critics abounded. Amid protests over the Vietnam war and race riots, NASA engineers kept their heads down and their slide rules busy.

2. Harness incongruence. In any large organization there is pressure to suppress dissent. That can be deadly, as it was for NASA in the two space shuttle failures — Challenger and Columbia — each of which killed all seven crew members. Leading up to both tragedies, the fact that engineers grew concerned about a technical problem they did not fully understand, but they could not make a quantitative case; and were consequently ignored.

After the bad years of the shuttle disasters, the practice of harnessing incongruence, and learning from mistakes, has staged something of a revival at NASA, which has since successfully sent unmanned craft to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Says Adam Stelzner, a NASA engineer, “Listen to all that the problem has to say, do not make assumptions or commit to a plan of action based on them until the deepest truth presents itself ”.

3. Delegate but decide. NASA realized early on that it needed help. About 90% of Apollo’s budget was spent on contractors from the most varied places. NASA itself was, therefore, more of a confederation than a single agency.

With so many players involved, turf wars were unavoidable. NASA Administrator James Webb coined the phrase Space Age Management to describe how he tried to manage conflicts and ensure final decisions were made by headquarters. Unfortunately, Webb’s mastery of the complex network was not as thorough as he believed. The death of three astronauts during a routine test in 1967 was traced to deficiencies Webb had been unaware of. Failure, in this case, was as instructive as success.

4. Effectiveness and elegance. Aesthetically, the Apollo mission was poor. The module that touched down on the moon looked like an oversize version of a kid’s cardboard science project, all right angles and skinny legs. Apollo’s return to Earth was equally unglamorous. The spaceship that left the launch pad was awesome; what was, by plan, to be rescued from the Pacific Ocean was a stubby cone weighing just 0.2% of the majestic original. But what looks clunky and awkward to an outsider may appear elegant to an engineer. Engineering inelegance, by contrast, would be redesigning a machine without fully anticipating the consequences.

Most of the people alive today had not yet arrived on the planet when Armstrong, Aldrin and Commander Michael Collins returned to it after their historic voyage. Never mind, though. The moon landing was a victory for all of the human race, past, present, and future.

(Peter Coy. Bloomberg Businessweek, 22.07.2019. Adapted.)

The fragment from the third paragraph “however valuable the - FGV 2020

Inglês - 2020Read the text

There’s something faintly embarrassing about the 50th anniversary of the first moonwalk. It was just so long ago. It’s no longer “we” who put a man on the moon, it’s “they” who put a man on the moon. So why can’t “we” do it? It’s hard not to feel that for all the technological advances of the last halfcentury, America has lost something — the ability to unite and overcome long odds to achieve greatness.

At one level, this is silly. The U.S. stopped going to the moon because Americans stopped seeing the point of it, not because they stopped being capable of it. Still, the historic Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs do have something to teach us. Months before the moon landing, the journal Science wrote that the space program’s “most valuable spin-off of all will be human rather than technological: better knowledge of how to plan, coordinate and monitor the multitudinous and varied activities of the organizations required to accomplish great social undertakings.” So, here, lessons the Apollo has left behind.

1. _____________ President John Kennedy simplified NASA’s job with his 1961 address to Congress committing to “the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” From then on, any decision was made by whether it would aid or impede the agency in meeting that deadline. Experiments that were too heavy were shelved, however valuable they might have been. Technologies that were superior but not ready for deployment were set aside. Having a North Star to pursue was essential, because skeptics and critics abounded. Amid protests over the Vietnam war and race riots, NASA engineers kept their heads down and their slide rules busy.

2. Harness incongruence. In any large organization there is pressure to suppress dissent. That can be deadly, as it was for NASA in the two space shuttle failures — Challenger and Columbia — each of which killed all seven crew members. Leading up to both tragedies, the fact that engineers grew concerned about a technical problem they did not fully understand, but they could not make a quantitative case; and were consequently ignored.

After the bad years of the shuttle disasters, the practice of harnessing incongruence, and learning from mistakes, has staged something of a revival at NASA, which has since successfully sent unmanned craft to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Says Adam Stelzner, a NASA engineer, “Listen to all that the problem has to say, do not make assumptions or commit to a plan of action based on them until the deepest truth presents itself ”.

3. Delegate but decide. NASA realized early on that it needed help. About 90% of Apollo’s budget was spent on contractors from the most varied places. NASA itself was, therefore, more of a confederation than a single agency.

With so many players involved, turf wars were unavoidable. NASA Administrator James Webb coined the phrase Space Age Management to describe how he tried to manage conflicts and ensure final decisions were made by headquarters. Unfortunately, Webb’s mastery of the complex network was not as thorough as he believed. The death of three astronauts during a routine test in 1967 was traced to deficiencies Webb had been unaware of. Failure, in this case, was as instructive as success.

4. Effectiveness and elegance. Aesthetically, the Apollo mission was poor. The module that touched down on the moon looked like an oversize version of a kid’s cardboard science project, all right angles and skinny legs. Apollo’s return to Earth was equally unglamorous. The spaceship that left the launch pad was awesome; what was, by plan, to be rescued from the Pacific Ocean was a stubby cone weighing just 0.2% of the majestic original. But what looks clunky and awkward to an outsider may appear elegant to an engineer. Engineering inelegance, by contrast, would be redesigning a machine without fully anticipating the consequences.

Most of the people alive today had not yet arrived on the planet when Armstrong, Aldrin and Commander Michael Collins returned to it after their historic voyage. Never mind, though. The moon landing was a victory for all of the human race, past, present, and future.

(Peter Coy. Bloomberg Businessweek, 22.07.2019. Adapted.)

The expression “that deadline”, in the third paragraph, - FGV 2020

Inglês - 2020Read the text

There’s something faintly embarrassing about the 50th anniversary of the first moonwalk. It was just so long ago. It’s no longer “we” who put a man on the moon, it’s “they” who put a man on the moon. So why can’t “we” do it? It’s hard not to feel that for all the technological advances of the last halfcentury, America has lost something — the ability to unite and overcome long odds to achieve greatness.

At one level, this is silly. The U.S. stopped going to the moon because Americans stopped seeing the point of it, not because they stopped being capable of it. Still, the historic Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs do have something to teach us. Months before the moon landing, the journal Science wrote that the space program’s “most valuable spin-off of all will be human rather than technological: better knowledge of how to plan, coordinate and monitor the multitudinous and varied activities of the organizations required to accomplish great social undertakings.” So, here, lessons the Apollo has left behind.

1. _____________ President John Kennedy simplified NASA’s job with his 1961 address to Congress committing to “the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” From then on, any decision was made by whether it would aid or impede the agency in meeting that deadline. Experiments that were too heavy were shelved, however valuable they might have been. Technologies that were superior but not ready for deployment were set aside. Having a North Star to pursue was essential, because skeptics and critics abounded. Amid protests over the Vietnam war and race riots, NASA engineers kept their heads down and their slide rules busy.

2. Harness incongruence. In any large organization there is pressure to suppress dissent. That can be deadly, as it was for NASA in the two space shuttle failures — Challenger and Columbia — each of which killed all seven crew members. Leading up to both tragedies, the fact that engineers grew concerned about a technical problem they did not fully understand, but they could not make a quantitative case; and were consequently ignored.

After the bad years of the shuttle disasters, the practice of harnessing incongruence, and learning from mistakes, has staged something of a revival at NASA, which has since successfully sent unmanned craft to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Says Adam Stelzner, a NASA engineer, “Listen to all that the problem has to say, do not make assumptions or commit to a plan of action based on them until the deepest truth presents itself ”.

3. Delegate but decide. NASA realized early on that it needed help. About 90% of Apollo’s budget was spent on contractors from the most varied places. NASA itself was, therefore, more of a confederation than a single agency.

With so many players involved, turf wars were unavoidable. NASA Administrator James Webb coined the phrase Space Age Management to describe how he tried to manage conflicts and ensure final decisions were made by headquarters. Unfortunately, Webb’s mastery of the complex network was not as thorough as he believed. The death of three astronauts during a routine test in 1967 was traced to deficiencies Webb had been unaware of. Failure, in this case, was as instructive as success.

4. Effectiveness and elegance. Aesthetically, the Apollo mission was poor. The module that touched down on the moon looked like an oversize version of a kid’s cardboard science project, all right angles and skinny legs. Apollo’s return to Earth was equally unglamorous. The spaceship that left the launch pad was awesome; what was, by plan, to be rescued from the Pacific Ocean was a stubby cone weighing just 0.2% of the majestic original. But what looks clunky and awkward to an outsider may appear elegant to an engineer. Engineering inelegance, by contrast, would be redesigning a machine without fully anticipating the consequences.

Most of the people alive today had not yet arrived on the planet when Armstrong, Aldrin and Commander Michael Collins returned to it after their historic voyage. Never mind, though. The moon landing was a victory for all of the human race, past, present, and future.

(Peter Coy. Bloomberg Businessweek, 22.07.2019. Adapted.)

Choose the alternative proposing the subtitle that would - FGV 2020

Inglês - 2020Read the text

There’s something faintly embarrassing about the 50th anniversary of the first moonwalk. It was just so long ago. It’s no longer “we” who put a man on the moon, it’s “they” who put a man on the moon. So why can’t “we” do it? It’s hard not to feel that for all the technological advances of the last halfcentury, America has lost something — the ability to unite and overcome long odds to achieve greatness.

At one level, this is silly. The U.S. stopped going to the moon because Americans stopped seeing the point of it, not because they stopped being capable of it. Still, the historic Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs do have something to teach us. Months before the moon landing, the journal Science wrote that the space program’s “most valuable spin-off of all will be human rather than technological: better knowledge of how to plan, coordinate and monitor the multitudinous and varied activities of the organizations required to accomplish great social undertakings.” So, here, lessons the Apollo has left behind.

1. _____________ President John Kennedy simplified NASA’s job with his 1961 address to Congress committing to “the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” From then on, any decision was made by whether it would aid or impede the agency in meeting that deadline. Experiments that were too heavy were shelved, however valuable they might have been. Technologies that were superior but not ready for deployment were set aside. Having a North Star to pursue was essential, because skeptics and critics abounded. Amid protests over the Vietnam war and race riots, NASA engineers kept their heads down and their slide rules busy.

2. Harness incongruence. In any large organization there is pressure to suppress dissent. That can be deadly, as it was for NASA in the two space shuttle failures — Challenger and Columbia — each of which killed all seven crew members. Leading up to both tragedies, the fact that engineers grew concerned about a technical problem they did not fully understand, but they could not make a quantitative case; and were consequently ignored.

After the bad years of the shuttle disasters, the practice of harnessing incongruence, and learning from mistakes, has staged something of a revival at NASA, which has since successfully sent unmanned craft to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Says Adam Stelzner, a NASA engineer, “Listen to all that the problem has to say, do not make assumptions or commit to a plan of action based on them until the deepest truth presents itself ”.

3. Delegate but decide. NASA realized early on that it needed help. About 90% of Apollo’s budget was spent on contractors from the most varied places. NASA itself was, therefore, more of a confederation than a single agency.

With so many players involved, turf wars were unavoidable. NASA Administrator James Webb coined the phrase Space Age Management to describe how he tried to manage conflicts and ensure final decisions were made by headquarters. Unfortunately, Webb’s mastery of the complex network was not as thorough as he believed. The death of three astronauts during a routine test in 1967 was traced to deficiencies Webb had been unaware of. Failure, in this case, was as instructive as success.

4. Effectiveness and elegance. Aesthetically, the Apollo mission was poor. The module that touched down on the moon looked like an oversize version of a kid’s cardboard science project, all right angles and skinny legs. Apollo’s return to Earth was equally unglamorous. The spaceship that left the launch pad was awesome; what was, by plan, to be rescued from the Pacific Ocean was a stubby cone weighing just 0.2% of the majestic original. But what looks clunky and awkward to an outsider may appear elegant to an engineer. Engineering inelegance, by contrast, would be redesigning a machine without fully anticipating the consequences.

Most of the people alive today had not yet arrived on the planet when Armstrong, Aldrin and Commander Michael Collins returned to it after their historic voyage. Never mind, though. The moon landing was a victory for all of the human race, past, present, and future.

(Peter Coy. Bloomberg Businessweek, 22.07.2019. Adapted.)

In the fragment from the second paragraph “most valuable - FGV 2020

Inglês - 2020Read the text

There’s something faintly embarrassing about the 50th anniversary of the first moonwalk. It was just so long ago. It’s no longer “we” who put a man on the moon, it’s “they” who put a man on the moon. So why can’t “we” do it? It’s hard not to feel that for all the technological advances of the last halfcentury, America has lost something — the ability to unite and overcome long odds to achieve greatness.

At one level, this is silly. The U.S. stopped going to the moon because Americans stopped seeing the point of it, not because they stopped being capable of it. Still, the historic Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs do have something to teach us. Months before the moon landing, the journal Science wrote that the space program’s “most valuable spin-off of all will be human rather than technological: better knowledge of how to plan, coordinate and monitor the multitudinous and varied activities of the organizations required to accomplish great social undertakings.” So, here, lessons the Apollo has left behind.

1. _____________ President John Kennedy simplified NASA’s job with his 1961 address to Congress committing to “the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” From then on, any decision was made by whether it would aid or impede the agency in meeting that deadline. Experiments that were too heavy were shelved, however valuable they might have been. Technologies that were superior but not ready for deployment were set aside. Having a North Star to pursue was essential, because skeptics and critics abounded. Amid protests over the Vietnam war and race riots, NASA engineers kept their heads down and their slide rules busy.

2. Harness incongruence. In any large organization there is pressure to suppress dissent. That can be deadly, as it was for NASA in the two space shuttle failures — Challenger and Columbia — each of which killed all seven crew members. Leading up to both tragedies, the fact that engineers grew concerned about a technical problem they did not fully understand, but they could not make a quantitative case; and were consequently ignored.

After the bad years of the shuttle disasters, the practice of harnessing incongruence, and learning from mistakes, has staged something of a revival at NASA, which has since successfully sent unmanned craft to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Says Adam Stelzner, a NASA engineer, “Listen to all that the problem has to say, do not make assumptions or commit to a plan of action based on them until the deepest truth presents itself ”.

3. Delegate but decide. NASA realized early on that it needed help. About 90% of Apollo’s budget was spent on contractors from the most varied places. NASA itself was, therefore, more of a confederation than a single agency.

With so many players involved, turf wars were unavoidable. NASA Administrator James Webb coined the phrase Space Age Management to describe how he tried to manage conflicts and ensure final decisions were made by headquarters. Unfortunately, Webb’s mastery of the complex network was not as thorough as he believed. The death of three astronauts during a routine test in 1967 was traced to deficiencies Webb had been unaware of. Failure, in this case, was as instructive as success.

4. Effectiveness and elegance. Aesthetically, the Apollo mission was poor. The module that touched down on the moon looked like an oversize version of a kid’s cardboard science project, all right angles and skinny legs. Apollo’s return to Earth was equally unglamorous. The spaceship that left the launch pad was awesome; what was, by plan, to be rescued from the Pacific Ocean was a stubby cone weighing just 0.2% of the majestic original. But what looks clunky and awkward to an outsider may appear elegant to an engineer. Engineering inelegance, by contrast, would be redesigning a machine without fully anticipating the consequences.

Most of the people alive today had not yet arrived on the planet when Armstrong, Aldrin and Commander Michael Collins returned to it after their historic voyage. Never mind, though. The moon landing was a victory for all of the human race, past, present, and future.

(Peter Coy. Bloomberg Businessweek, 22.07.2019. Adapted.)

In the excerpt from the second paragraph “The U.S. stopped - FGV 2020

Inglês - 2020Read the text

There’s something faintly embarrassing about the 50th anniversary of the first moonwalk. It was just so long ago. It’s no longer “we” who put a man on the moon, it’s “they” who put a man on the moon. So why can’t “we” do it? It’s hard not to feel that for all the technological advances of the last halfcentury, America has lost something — the ability to unite and overcome long odds to achieve greatness.

At one level, this is silly. The U.S. stopped going to the moon because Americans stopped seeing the point of it, not because they stopped being capable of it. Still, the historic Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs do have something to teach us. Months before the moon landing, the journal Science wrote that the space program’s “most valuable spin-off of all will be human rather than technological: better knowledge of how to plan, coordinate and monitor the multitudinous and varied activities of the organizations required to accomplish great social undertakings.” So, here, lessons the Apollo has left behind.

1. _____________ President John Kennedy simplified NASA’s job with his 1961 address to Congress committing to “the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” From then on, any decision was made by whether it would aid or impede the agency in meeting that deadline. Experiments that were too heavy were shelved, however valuable they might have been. Technologies that were superior but not ready for deployment were set aside. Having a North Star to pursue was essential, because skeptics and critics abounded. Amid protests over the Vietnam war and race riots, NASA engineers kept their heads down and their slide rules busy.

2. Harness incongruence. In any large organization there is pressure to suppress dissent. That can be deadly, as it was for NASA in the two space shuttle failures — Challenger and Columbia — each of which killed all seven crew members. Leading up to both tragedies, the fact that engineers grew concerned about a technical problem they did not fully understand, but they could not make a quantitative case; and were consequently ignored.

After the bad years of the shuttle disasters, the practice of harnessing incongruence, and learning from mistakes, has staged something of a revival at NASA, which has since successfully sent unmanned craft to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Says Adam Stelzner, a NASA engineer, “Listen to all that the problem has to say, do not make assumptions or commit to a plan of action based on them until the deepest truth presents itself ”.

3. Delegate but decide. NASA realized early on that it needed help. About 90% of Apollo’s budget was spent on contractors from the most varied places. NASA itself was, therefore, more of a confederation than a single agency.

With so many players involved, turf wars were unavoidable. NASA Administrator James Webb coined the phrase Space Age Management to describe how he tried to manage conflicts and ensure final decisions were made by headquarters. Unfortunately, Webb’s mastery of the complex network was not as thorough as he believed. The death of three astronauts during a routine test in 1967 was traced to deficiencies Webb had been unaware of. Failure, in this case, was as instructive as success.

4. Effectiveness and elegance. Aesthetically, the Apollo mission was poor. The module that touched down on the moon looked like an oversize version of a kid’s cardboard science project, all right angles and skinny legs. Apollo’s return to Earth was equally unglamorous. The spaceship that left the launch pad was awesome; what was, by plan, to be rescued from the Pacific Ocean was a stubby cone weighing just 0.2% of the majestic original. But what looks clunky and awkward to an outsider may appear elegant to an engineer. Engineering inelegance, by contrast, would be redesigning a machine without fully anticipating the consequences.

Most of the people alive today had not yet arrived on the planet when Armstrong, Aldrin and Commander Michael Collins returned to it after their historic voyage. Never mind, though. The moon landing was a victory for all of the human race, past, present, and future.

(Peter Coy. Bloomberg Businessweek, 22.07.2019. Adapted.)

In the first and second paragraphs the author expresses - FGV 2020

Inglês - 2020Read the text

There’s something faintly embarrassing about the 50th anniversary of the first moonwalk. It was just so long ago. It’s no longer “we” who put a man on the moon, it’s “they” who put a man on the moon. So why can’t “we” do it? It’s hard not to feel that for all the technological advances of the last halfcentury, America has lost something — the ability to unite and overcome long odds to achieve greatness.

At one level, this is silly. The U.S. stopped going to the moon because Americans stopped seeing the point of it, not because they stopped being capable of it. Still, the historic Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs do have something to teach us. Months before the moon landing, the journal Science wrote that the space program’s “most valuable spin-off of all will be human rather than technological: better knowledge of how to plan, coordinate and monitor the multitudinous and varied activities of the organizations required to accomplish great social undertakings.” So, here, lessons the Apollo has left behind.

1. _____________ President John Kennedy simplified NASA’s job with his 1961 address to Congress committing to “the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” From then on, any decision was made by whether it would aid or impede the agency in meeting that deadline. Experiments that were too heavy were shelved, however valuable they might have been. Technologies that were superior but not ready for deployment were set aside. Having a North Star to pursue was essential, because skeptics and critics abounded. Amid protests over the Vietnam war and race riots, NASA engineers kept their heads down and their slide rules busy.

2. Harness incongruence. In any large organization there is pressure to suppress dissent. That can be deadly, as it was for NASA in the two space shuttle failures — Challenger and Columbia — each of which killed all seven crew members. Leading up to both tragedies, the fact that engineers grew concerned about a technical problem they did not fully understand, but they could not make a quantitative case; and were consequently ignored.

After the bad years of the shuttle disasters, the practice of harnessing incongruence, and learning from mistakes, has staged something of a revival at NASA, which has since successfully sent unmanned craft to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Says Adam Stelzner, a NASA engineer, “Listen to all that the problem has to say, do not make assumptions or commit to a plan of action based on them until the deepest truth presents itself ”.

3. Delegate but decide. NASA realized early on that it needed help. About 90% of Apollo’s budget was spent on contractors from the most varied places. NASA itself was, therefore, more of a confederation than a single agency.

With so many players involved, turf wars were unavoidable. NASA Administrator James Webb coined the phrase Space Age Management to describe how he tried to manage conflicts and ensure final decisions were made by headquarters. Unfortunately, Webb’s mastery of the complex network was not as thorough as he believed. The death of three astronauts during a routine test in 1967 was traced to deficiencies Webb had been unaware of. Failure, in this case, was as instructive as success.

4. Effectiveness and elegance. Aesthetically, the Apollo mission was poor. The module that touched down on the moon looked like an oversize version of a kid’s cardboard science project, all right angles and skinny legs. Apollo’s return to Earth was equally unglamorous. The spaceship that left the launch pad was awesome; what was, by plan, to be rescued from the Pacific Ocean was a stubby cone weighing just 0.2% of the majestic original. But what looks clunky and awkward to an outsider may appear elegant to an engineer. Engineering inelegance, by contrast, would be redesigning a machine without fully anticipating the consequences.