FGV

Exibindo questões de 1001 a 1100.

São características das chamadas sociedades do Antigo - FGV 2014

História - 2014São características das chamadas sociedades

Sobre as novas condições geográficas da economia global - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014Serviços de atendimento ao consumidor, call centers e serviços de transcrição médica foram só o começo. A possibilidade de terceirizar serviços graças às TICs (tecnologias de informação e comunicação) aumentou a cada dia a capacidade de administrar os equipamentos físicos e as redes de computadores de empresas e de manter e desenvolver programas de negócios; [...] o que começou como arbitragem de salários ou simples corte de custos mandando para o exterior alguns empregos menores se tornou um enorme sistema projetado para transformar uma empresa em uma eficiente operação global.

No Brasil há a presença de variados biomas e ecossistemas - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014No Brasil há a presença de variados biomas e ecossistemas ricos em espécies animais, vegetais e micro-organismos. É o país com maior diversidade de anfíbios do mundo: 516 espécies. Possui 522 espécies de mamíferos, das quais 68 são endêmicas; 468 espécies de répteis, das quais 172 são endêmicas, e 1622 espécies de aves (uma em cada seis espécies de aves do mundo ocorre no Brasil).

Mais do que um problema relacionado à raça, o homicídio no - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014Mais do que um problema relacionado à raça, o homicídio no Brasil sempre se caracterizou por ser um tipo de crime vinculado ao território. Nas últimas décadas, as principais vítimas e autores de assassinatos foram homens, jovens, moradores de bairros com pouca infraestrutura urbana dos grandes centros metropolitanos. Eles mataram e morreram por viverem em locais com grande quantidade de armas, marcados pela desordem. São territórios com frágil presença policial, vulneráveis à ação daqueles que estão dispostos a tentar exercer o domínio pela violência.

Estudos ambientais revelaram que o ferro é um dos metais - FGV 2015

Química - 2014Estudos ambientais revelaram que o ferro é um dos metais presentes em maior quantidade na atmosfera, apresentando-se na forma do íon de ferro 3+ hidratado, [Fe(H2O)6]3+. O íon de ferro na atmosfera se hidrolisa de acordo com a equação

[Fe(H2 O)6 ] 3+ ↔ [Fe(H2 O)5 OH]2+ + H+

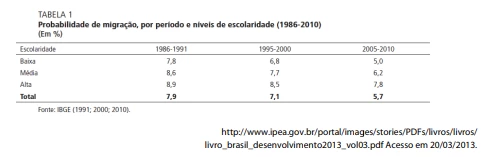

Pesquisa recente publicada pelo Instituto de Pesquisas- FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014Pesquisa recente publicada pelo Instituto de Pesquisas Econômicas (IPEA) sobre as migrações internas no Brasil evidencia existir uma relação entre probabilidade de migração e níveis de escolaridade, conforme tabela abaixo.

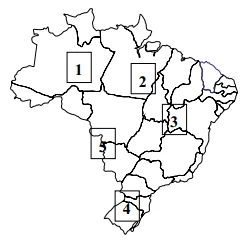

A diferenciação espaço-temporal da produção agrícola - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014A diferenciação espaço-temporal da produção agrícola constitui o conteúdo próprio daquilo que alguns autores chamam de heterogeneidade estrutural da agropecuária brasileira [...]. Como a modernização da agricultura significou, em um primeiro momento, a integração técnica com a indústria e, em um segundo momento, a integração de capitais, também ela esteve algumas regiões, beneficiando grupos econômicos específicos identificados por seus produtos.

A Agência Internacional de Energia Atômica (AIEA) confirmou - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014A Agência Internacional de Energia Atômica (AIEA) confirmou, em um novo relatório, que o Irã segue cumprindo o pactuado no grande acordo nuclear interino assinado em novembro do ano passado com seis grandes potências.

Um referendo realizado no dia 17 de março na Crimeia, uma - FGV 2014

História - 2014Um referendo realizado no dia 17 de março na Crimeia, uma República Autônoma ucraniana de maioria russa, aprovou com 96,8% dos votos a adesão da região à Federação Russa. O referendo é o ápice de uma escalada de tensão que atinge a região há mais de um mês, com uma escalada militar russa e ucraniana na região gerada após a deposição do presidente ucraniano Viktor Yanukovich.

O projeto de lei 21626/11 – conhecido como Marco Civil da - FGV 2014

História - 2014O projeto de lei 21626/11 – conhecido como Marco Civil da Internet – é um projeto de lei que estabelece princípios e garantias do uso da rede no Brasil. Segundo o deputado Alessandro Molon (PTRJ), autor da proposta, a ideia é que o marco civil funcione como uma espécie de "Constituição" da internet, definindo direitos e deveres de usuários e provedores da web no Brasil.

A Venezuela tem enfrentado momentos de tensão desde o - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014A Venezuela tem enfrentado momentos de tensão desde o início de fevereiro, com protestos de estudantes e opositores contra o governo. A situação se agravou em 12 de fevereiro, quando uma manifestação contra o presidente Nicolás Maduro terminou com três mortos e mais de 20 feridos.

Começou com a instituição do divórcio no país, em 1907, - FGV 2014

História - 2014Começou com a instituição do divórcio no país, em 1907, décadas antes dos vizinhos de América Latina. Continuou com a regulamentação da jornada de oito horas, sete anos depois, com o direito de voto às mulheres, em 1932, até uma série de recentes medidas modernizadoras. O motivo da fascinação do mundo pelo Uruguai parece ser a vanguarda e a reinvenção constantes no país.

http://zerohora.clicrbs.com.br/rs/mundo/noticia/2013/12/o-uruguaiganha-o-mundo-4371416.html, acesso em 15/02/2014.

Sobre as recentes medidas modernizantes aprovadas pelo parlamento uruguaio e seus desdobramentos, considere as seguintes afirmações:

I. Em 2012, o parlamento uruguaio aprovou a descriminalização do aborto, desde que realizado até a 12ª semana de gestação. Entretanto, o presidente José Mujica vetou a implementação da medida, alegando questões éticas.

II. Em 2013, o parlamento uruguaio aprovou o casamento homossexual, se tornando o segundo país latino-americano a tornar lei a união entre pessoas do mesmo gênero, depois da Argentina.

III. Em 2013, o parlamento uruguaio aprovou uma lei descriminalizando o uso e conferindo ao Estado o papel de regulador da produção e da comercialização da maconha.

Uma jarra de limonada contém 500 g de suco puro de limão, - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Uma jarra de limonada contém 500 g de suco puro de limão, 500 g de açúcar e 2 kg de água. Sabe-se que:

25 g de suco puro de limão contêm 100 calorias;

100 g de açúcar contêm 386 calorias;

água não contém calorias.

Um cubo de 1 m de aresta foi subdividido em cubos menores - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Um cubo de 1 m de aresta foi subdividido em cubos menores de 1 mm de aresta, sem que houvesse perdas ou sobras de material.

A soma dos algarismos do resultado da expressão numérica - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014A soma dos algarismos do resultado da expressão numérica

O número natural representado por x possui todos os - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014O número natural representado por x possui todos os algarismos iguais a 2, e o número natural representado por y possui todos os algarismos iguais a 1. Sabe-se que x possui 2n algarismos, e que y possui n algarismos, com n sendo um inteiro positivo.

Sejam a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6, a7 e a8 elementos - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Sejam a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6, a7 e a8 elementos distintos do conjunto {–7, –5, –3, –2, 2, 4, 6, 13}. Nessas condições, o menor valor possível da expressão

Uma impressora deveria imprimir todos os números inteiros - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Uma impressora deveria imprimir todos os números inteiros de 1 até 225, em ordem crescente e um de cada vez. A tinta da impressora acabou antes que o serviço fosse completado, tendo deixado de imprimir um total de 452 algarismos.

Na reta real, os pontos P e Q correspondem, respectivamente - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Na reta real, os pontos P e Q correspondem, respectivamente, aos números –5 e 3. R e S são pontos distintos nessa mesma reta, e a distância de cada um deles até o ponto P é igual ao dobro da distância deles até o ponto Q.

O total de x moedas convencionais (cara e coroa nas faces) - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014O total de x moedas convencionais (cara e coroa nas faces) estão sobre uma mesa. Dessas moedas 1/5, está em posição de coroa, ou seja, com a face coroa voltada para cima. Se invertermos o lado de 3 moedas que estão em posição de cara1/4, das moedas ficará em posição de coroa.

Se o sétimo termo de uma progressão geométrica de termos - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Se o sétimo termo de uma progressão geométrica de termos positivos é 20, e o décimo terceiro termo é 11,

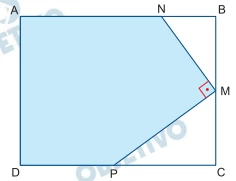

A figura indica um retângulo ABCD, com AB = 10 cm e AD = 6 - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014A figura indica um retângulo ABCD, com AB = 10 cm e AD = 6 cm. Os pontos M, N e P estão nos lados do retângulo, sendo que M é ponto médio de BC, e AN = 8 cm.

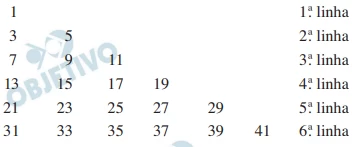

Os números naturais ímpares foram dispostos em um arranjo - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Os números naturais ímpares foram dispostos em um arranjo triangular, como indica a figura.

No interior e no exterior do triângulo ABC, com dados - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014No interior e no exterior do triângulo ABC, com dados indicados na figura, serão marcados os pontos distintos P’ e P”. Ligando-se convenientemente cada um desses pontos com os vértices do triângulo ABC, os polígonos obtidos serão pipas côncavas de área 16.

13 A A atual moeda de 1 real é composta de aço inox no - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014A atual moeda de 1 real é composta de aço inox no círculo central e de aço inox revestido de bronze na coroa circular. Essa moeda possui diâmetro e espessura aproximados de 26 e 2 milímetros, respectivamente. Uma corda no círculo dessa moeda que seja tangente ao círculo central de aço inox mede, aproximadamente, 18 milímetros.

Seja k um número real tal que os gráficos das funções reais - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Seja k um número real tal que os gráficos das funções reais dadas por y = |x| e y = –|x|+ k delimitem um polígono de área 16.

Admita que (A, B, C, D, E, F) seja uma sêxtupla ordenada de - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Admita que (A, B, C, D, E, F) seja uma sêxtupla ordenada de números inteiros maiores ou iguais a 1 tais que A ≤ B ≤ C ≤ D ≤ E ≤ F.

A respeito dos números que compõem essa sêxtupla, sabe-se que:

a mediana e a moda da sequência A, B, C, D, E, F são, ambas, iguais a 2;

a diferença entre F e A é 19.

Se a soma dos inversos das raízes reais da equação - FUVEST 2023

Matemática - 2014Se a soma dos inversos das raízes reais da equação polinomial x2 – 2kx + 36 = 0, em que k é uma constante

Existem três possibilidades de rota (A, B e C) para a - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Existem três possibilidades de rota (A, B e C) para a construção de uma nova linha do metrô. De acordo com estudos iniciais de viabilidade, a probabilidade de que a rota B seja escolhida é 10% maior do que a probabilidade de que a rota C seja escolhida. Os mesmos estudos revelam que a probabilidade de que a rota C seja escolhida é 20% maior do que a probabilidade de que rota A seja escolhida.

O conjunto solução da equação (x2 – 14)2 · (3y – 9)3 = 108, - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014O conjunto solução da equação (x2 – 14)2 · (3y – 9)3 = 108, com x e y inteiros, possui n pares ordenados (x, y).

Com relação ao polinômio de coeficientes reais dado por - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Com relação ao polinômio de coeficientes reais dado por P(x) = x4 + ax3 + bx2 + cx + d, sabe-se que P(2i) = P(2 + i) = 0, com i2 = –1.

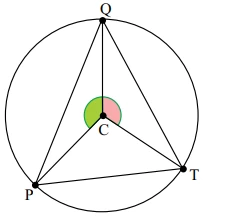

O triângulo PQT, indicado na figura, está inscrito em uma - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014O triângulo PQT, indicado na figura, está inscrito em uma circunferência de centro C, sendo que as medidas dos ângulos PCˆQ e TCˆQ são, respectivamente, iguais a α e

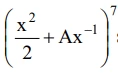

No desenvolvimento do binômio 7 1 2 Ax 2 x- FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014No desenvolvimento do binômio  segundo a ordem decrescente de seus expoentes, o quinto termo é igual a

segundo a ordem decrescente de seus expoentes, o quinto termo é igual a  com A e B constantes racionais.

com A e B constantes racionais.

Um semáforo de trânsito está regulado de forma que a luz - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Um semáforo de trânsito está regulado de forma que a luz verde fica acesa por 30 segundos, em seguida se acende a luz amarela por 3 segundos, e depois a luz vermelha por 30 segundos.

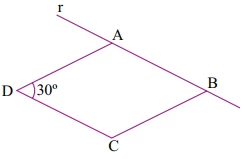

O losango ABCD, indicado na figura, tem lado de medida 6 cm - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014O losango ABCD, indicado na figura, tem lado de medida 6 cm. Esse losango será rotacionado em 360° em torno de uma reta r que contém seu lado AB.

Renato participou de uma sequência de seis apostas - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Renato participou de uma sequência de seis apostas consecutivas. Em cada aposta, ele arriscou ganhar ou perder metade do valor apostado. Renato começou apostando R$ 100,00 e, durante as demais apostas, sempre apostou todo o saldo do dinheiro que tinha ao final da aposta anterior. Sabe-se que Renato ganhou três e perdeu três das seis apostas.

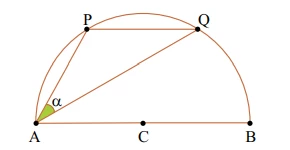

Os pontos P e Q estão em uma semicircunferência de centro C - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Os pontos P e Q estão em uma semicircunferência de centro C e diâmetro AB, formando com A o triângulo APQ, conforme indica a figura.

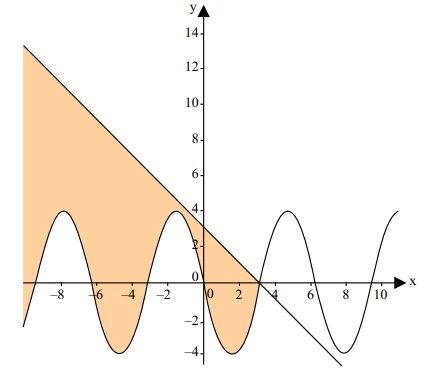

No gráfico, observam-se uma senoide de equação y = –4 sen x - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014No gráfico, observam-se uma senoide de equação y = –4 sen x e uma reta de coeficiente angular igual a –1, que intersecta a senoide e o eixo x no mesmo ponto do plano cartesiano.

Em uma urna, temos 32 objetos, que são: 8 dados brancos, 8 - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Em uma urna, temos 32 objetos, que são: 8 dados brancos, 8 dados pretos, 8 esferas brancas e 8 esferas pretas.

Investindo certo capital a juros compostos de k% ao mês, o - FGV 2014

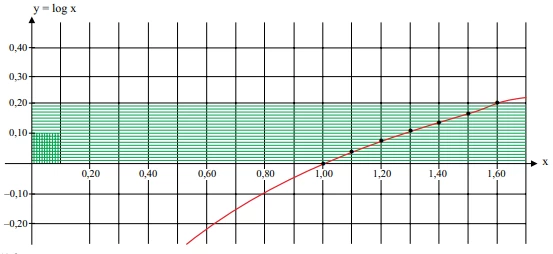

Matemática - 2014Investindo certo capital a juros compostos de k% ao mês, o capital investido será acrescido em 60% no período de 5 meses. Consultando dados do gráfico a seguir,

- FGV 2014

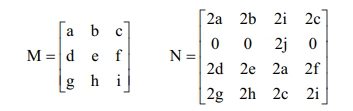

Matemática - 2014Sejam M3x3 e N4x4 as matrizes quadradas indicadas a seguir, com a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j sendo números reais.

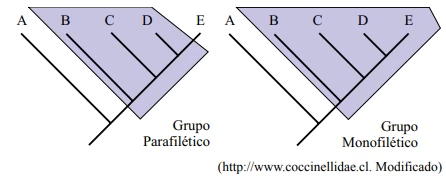

Os cladogramas a seguir ilustram os conceitos de grupos - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014Os cladogramas a seguir ilustram os conceitos de grupos parafiléticos e monofiléticos

A figura ilustra o momento do início da fusão de dois - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014A figura ilustra o momento do início da fusão de dois núcleos de células reprodutivas humanas sem anomalias.

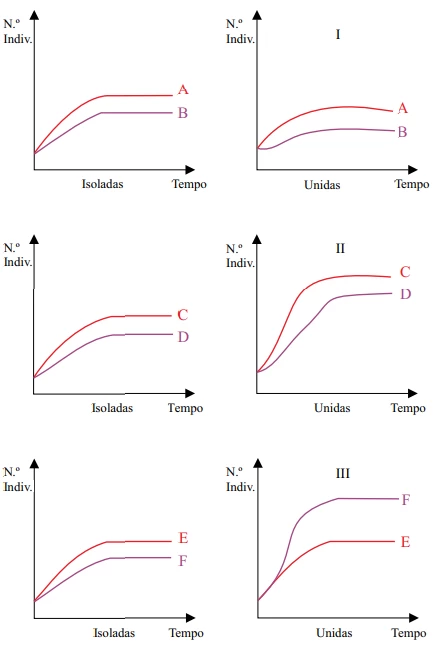

Analise os gráficos a seguir, os quais ilustram três - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014Analise os gráficos a seguir, os quais ilustram três interações ecológicas entre espécies diferentes.

Para realizar o teste do etilômetro, popularmente chamado - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014Para realizar o teste do etilômetro, popularmente chamado de bafômetro, uma pessoa precisa expirar um determinado volume de ar para dentro do equipamento, através de um bocal.

“Por volta de 1850, em Manchester, Inglaterra, predominava - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014“Por volta de 1850, em Manchester, Inglaterra, predominava uma população de mariposas brancas com algumas manchas negras. Após a Revolução Industrial, mariposas escuras passaram a ser encontradas em número cada vez maior, tornando-se mais frequentes, representando cerca de 98% de toda a população (I).

Estudos realizados pelo cientista inglês H. B. Kettlewell mostraram que, em regiões não poluídas, os pássaros atacavam principalmente as mariposas escuras, pois as brancas ficavam camufladas sobre os troncos cobertos de liquens brancos.

Com a industrialização, a fuligem expelida pelas chaminés determinou a morte dos liquens, deixando os troncos escuros e expostos (II)”.

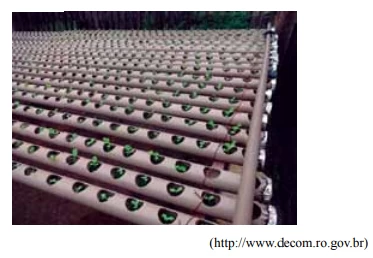

O cultivo de hortaliças hidropônicas é uma alternativa para - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014O cultivo de hortaliças hidropônicas é uma alternativa para a produção de alimentos em locais cujos solos estão contaminados. Nesta técnica agrícola, os vegetais são geralmente cultivados apoiados em instalações de tubos plásticos, não entrando em contato direto com o solo, conforme ilustra a figura.

Uma determinada característica genética de um grupo de - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014Uma determinada característica genética de um grupo de animais invertebrados é condicionada por apenas um par de alelos autossômicos. Estudos de genética de populações, nestes animais, mostraram que a frequência do alelo recessivo é três vezes maior que a frequência do alelo dominante, para a característica analisada em questão.

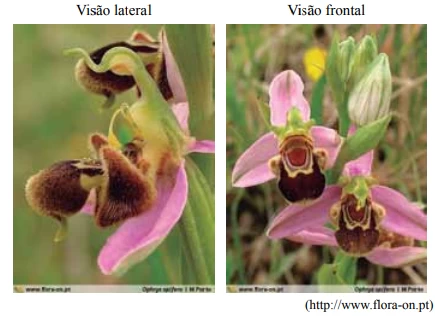

A orquídea Ophrys apifera, ilustrada em visão lateral e - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014A orquídea Ophrys apifera, ilustrada em visão lateral e frontal nas figuras, apresenta um formato que mimetiza as vespas fêmeas. São capazes de produzir também uma substância odorífera similar ao feromônio liberado por essas vespas fêmeas em épocas reprodutivas, atraindo, portanto, vespas machos que realizarão a polinização cruzada.

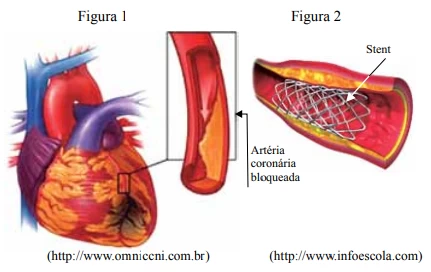

Um dos procedimentos médicos em casos de obstrução de - FUGV 2014

Biologia - 2014Um dos procedimentos médicos em casos de obstrução de vasos sanguíneos cardíacos, causada geralmente por acúmulo de placas de gordura nas paredes (Figura 1), é a colocação de um tubo metálico expansível em forma de malha, denominado stent (Figura 2), evitando o infarto do miocárdio.

Na difícil busca pela explicação científica sobre a origem - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014Na difícil busca pela explicação científica sobre a origem da vida no planeta Terra, uma das etapas consideradas essenciais é o surgimento de aglomerados de proteínas, os coacervatos, capazes de isolar um meio interno do ambiente externo, permitindo que reações bioquímicas ocorressem dentro dessas estruturas de forma diferenciada do meio externo.

Mosquitos psicodídeos são bastante comuns nos banheiros das - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014Mosquitos psicodídeos são bastante comuns nos banheiros das residências, sendo geralmente inofensivos ao ser humano, exceto quando ocorre o transporte de patógenos em suas pernas, ao pousarem em diferentes locais.

As figuras ilustram o adulto e a larva do inseto conhecido popularmente como “mosca de banheiro”.

A produção de adenosina trifosfato (ATP) nas células - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014A produção de adenosina trifosfato (ATP) nas células eucarióticas animais acontece, essencialmente, nas cristas mitocondriais, em função de uma cadeia de proteínas transportadoras de elétrons, a cadeia respiratória.

Leia a notícia a seguir. “Uma equipe de investigadores da - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014Leia a notícia a seguir.

“Uma equipe de investigadores da Escócia estudou três galináceos ginandromorfos, ou seja, com características de ambos os sexos. A figura mostra um dos galináceos estudados, batizado de Sam, cujo lado esquerdo do corpo apresenta a penugem esbranquiçada e os músculos bem desenvolvidos, como observado em galos. Já no lado direito do corpo, as penas são castanhas e os músculos mais delgados, como é normal nas galinhas. No caso dos galináceos, a determinação sexual ocorre pelo sistema ZW.”

A difilobotríase é uma parasitose adquirida pela ingestão - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014A difilobotríase é uma parasitose adquirida pela ingestão de carne de peixe crua, mal cozida, congelada ou defumada em temperaturas inadequadas, contaminada pela forma larval do agente etiológico.

O ciclo do parasita envolve a liberação de proglotes pelas fezes humanas repletas de ovos, que eclodem na água e passam a se hospedar sequencialmente em pequenos crustáceos, em pequenos peixes e, finalmente, em peixes maiores que, ao serem ingeridos nas condições citadas, contaminam os seres humanos.

Um grupo de estudantes percorria uma trilha pela Mata - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014Um grupo de estudantes percorria uma trilha pela Mata Atlântica, quando um deles observou, na ponta de um bambuzeiro, estruturas vegetais que, a princípio, desconheciam. Iniciaram então, sem grande aprofundamento, um curto “debate botânico científico” sobre a classificação de tais estruturas, devidamente registradas na imagem.

O anfiteatro era, para os romanos, parte de sua normalidade - FGV 2014

História - 2014O anfiteatro era, para os romanos, parte de sua normalidade cotidiana, um lugar no qual reafirmavam seus valores e sua concepção do “normal”. Nos anfiteatros eram expostos, para serem supliciados, bárbaros vencidos, inimigos que se haviam insurgido contra a ordem romana. Nos anfiteatros se supliciavam, também, bandidos e marginais, como por vezes os cristãos, que eram jogados às feras e dados como espetáculo, para o prazer de seus algozes ou daqueles que defendiam os valores normais da sociedade.

[A crise] do feudalismo deriva não propriamente do - FGV 2014

História - 2014[A crise] do feudalismo deriva não propriamente do renascimento do comércio em si mesmo, mas da maneira pela qual a estrutura feudal reage ao impacto da economia de mercado. O revivescimento do comércio (isto é, a instauração de um setor mercantil na economia e o desenvolvimento de um setor urbano na sociedade) pode promover, de um lado, a lenta dissolução dos laços servis, e de outro lado, o enrijecimento da servidão. (...) Nos dois setores, abre-se pois a crise social.

Sobre as relações entre os reinos ibéricos e a expansão - FGV 2014

História - 2014Sobre as relações entre os reinos ibéricos e a expansão ultramarina,

O paradoxo aparente do absolutismo na Europa ocidental era - FGV 2014

História - 2014O paradoxo aparente do absolutismo na Europa ocidental era que ele representava fundamentalmente um aparelho de proteção da propriedade dos privilégios aristocráticos, embora, ao mesmo tempo, os meios pelos quais tal proteção era concedida pudessem assegurar simultaneamente os interesses básicos das classes mercantis e manufatureiras nascentes. Essencialmente, o absolutismo era apenas isto: um aparelho de dominação feudal recolocado e reforçado, destinado a sujeitar as massas camponesas à sua posição tradicional. Nunca foi um árbitro entre a aristocracia e a burguesia, e menos ainda um instrumento da burguesia nascente contra a aristocracia: ele era a nova carapaça política de uma nobreza atemorizada.

Feitas as contas, a historiografia tradicional do - FGV 2014

Biologia - 2014Feitas as contas, a historiografia tradicional do bandeirantismo errou na proposição secundária (as bandeiras caçavam índios para vendê-los no Norte), mas acertou na principal (as bandeiras foram originadas pela quebra do tráfico atlântico): os anos 1625-50 configuram, incontestavelmente, um período de “fome de cativos”.

O trabalho escravo nas minas tinha singularidade, era uma - FGV 2014

História - 2014O trabalho escravo nas minas tinha singularidade, era uma realidade bem distinta das áreas agrícolas. O complexo meio social lhe permitia maior iniciativa e mobilidade.

(...) Nós temos essas verdades como evidentes por si mesmas - FGV 2014

História - 2014(...) Nós temos essas verdades como evidentes por si mesmas: que todos os homens nascem iguais; que o seu Criador os dotou de certos direitos inalienáveis, entre os quais a Vida, a Liberdade e a procura da Felicidade; que para garantir esses direitos, os homens instituem entre eles Governos, cujo justo poder emana do consentimento dos governados; que, se um governo, seja qual for a sua forma, chega a não reconhecer esses fins, o povo tem o direito de modificá-lo ou de aboli-lo e de instituir um novo governo, que fundará sobre tais princípios e de que ele organizará os poderes segundo as formas que lhe parecem mais próprias para garantir a sua Segurança e a sua Felicidade.

Em contraste com a estagnação e mesmo a decadência de - FGV 2014

História - 2014Em contraste com a estagnação e mesmo a decadência de outras regiões do Império, o vale do Paraíba do Sul apresentava-se em franco progresso, especialmente a partir da década de 1830-1840. Em torno dos novos-ricos dessa região, formar-se-ia um novo bloco de poder, cuja hegemonia, durante muitos anos, não seria contestada.

A nova entrada da pobreza indigente será não mais um - FGV 2014

História - 2014A nova entrada da pobreza indigente será não mais um fenômeno temporário do desemprego ou como resistência ao trabalho dos pobres não moralizados, mas como Criatura da própria sociedade industrial, como resíduo que, produzido por ela, nela não tem lugar. É em Londres que o sistema de fábrica despeja sua escória humana. Mais uma vez questiona-se o pensamento liberal em um dos seus pressupostos básicos, o laissez-faire.

Uns pedem ao governo leis severas de controle da superpopulação e medidas no sentido de se exportar o resíduo para as colônias.

Somente a partir de 1850 vai se observar um maior dinamismo - FGV 2014

História - 2014Somente a partir de 1850 vai se observar um maior dinamismo no desenvolvimento econômico do país em geral e de suas manufaturas, em particular. O crescimento do número de empresas industriais se faria com relativa rapidez.

Mas o que provocaria essas mudanças?

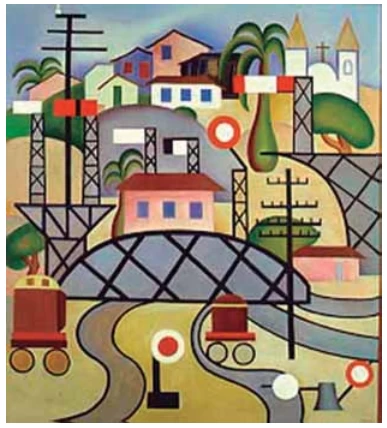

Observe o quadro Estrada de Ferro Central do Brasil (1924), - FGV 2014

História - 2014Observe o quadro Estrada de Ferro Central do Brasil (1924), de Tarsila do Amaral.

Observe os dois cartuns. Sobre as imagens, é correto afirma - FGV 2014

História - 2014Observe os dois cartuns.

Em 3 de outubro de 1953, o presidente Getúlio Vargas - FGV 2014

História - 2014Em 3 de outubro de 1953, o presidente Getúlio Vargas sancionou a Lei n.º 2.004, que criava a Petrobras.

Uma coluna de fumaça espessa e escura levantou-se na área - FGV 2014

História - 2014Uma coluna de fumaça espessa e escura levantou-se na área central de Santiago do Chile na manhã de uma terça-feira, 11 de setembro de 1973. Era um estranho acontecimento. Não parecia um incêndio qualquer, mas algo mais grave e ameaçador, especialmente porque minutos antes foi possível ouvir o ruído dos caças da Força Aérea do Chile em voos rasantes sobre o centro da cidade, onde fica o Palácio de La Moneda. O que ocorria não era fortuito.

O governo (...) Salvador Allende chegava ao fim com seu suicídio no interior do palácio, que estava sendo bombardeado. O golpe militar e o regime autoritário que se instaurou em seguida alterariam profundamente a história contemporânea do Chile.

O “socialismo real” agora enfrentava não apenas seus - FGV 2014

História - 2014O “socialismo real” agora enfrentava não apenas seus próprios problemas sistêmicos insolúveis mas também os de uma economia mundial mutante e problemática, na qual se achava cada vez mais integrado.

Com o colapso da URSS, a experiência do “socialismo realmente existente” chegou ao fim. Pois, mesmo onde os regimes comunistas sobreviveram e tiveram êxito, como na China, abandonaram a ideia original de uma economia única, centralmente controlada e estatalmente planejada, baseada num Estado completamente coletivizado.

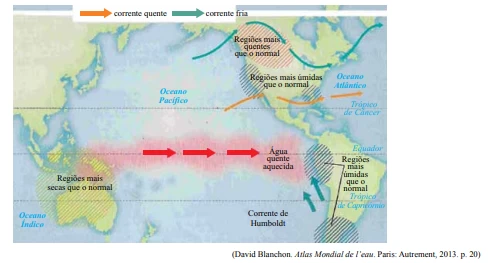

Analise o mapa que representa uma anomalia climática. - FGV 2014

História - 2014Analise o mapa que representa uma anomalia climática.

Uma tragédia se repetiu nesta sexta-feira (11/10), no sul - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014Uma tragédia se repetiu nesta sexta-feira (11/10), no sul da Itália. Mais um barco cheio de imigrantes afundou no Mar Mediterrâneo. Foi o segundo acidente com refugiados em uma semana. E há dados conflitantes sobre o número de mortos: entre 27 e 50 pessoas. Os sobreviventes em estado grave foram levados para Lampedusa, a mesma ilha que testemunhou o acidente com imigrantes da Somália e Eritreia, na quinta-feira passada [03/10], matando 339 pessoas.

No naufrágio desta sexta, ainda não se sabe as nacionalidades das vítimas, nem de onde o barco partiu

Considere um anúncio publicitário da maior empresa - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014Considere um anúncio publicitário da maior empresa agroquímica do mundo, fornecedora de sementes transgênicas, e o uso que se fez da cartografia.

mica do mundo, fornecedora de sementes transgênicas, e o - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014No decorrer do século XX, para a organização de projetos de criação de blocos econômicos, foi necessário superar rivalidades históricas. Isto ocorreu na Europa e também na América do Sul, quando o Brasil e a Argentina deixaram de lado as disputas por hegemonia e engendraram um acordo, na década de 1980, que posteriormente originou o Mercosul.

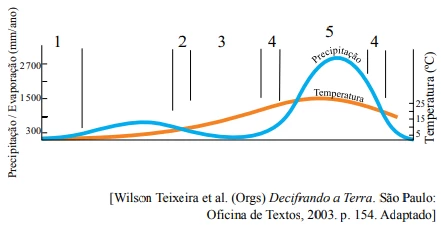

Analise a figura que relaciona temperatura, pluviosidade e - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014Analise a figura que relaciona temperatura, pluviosidade e vegetação.

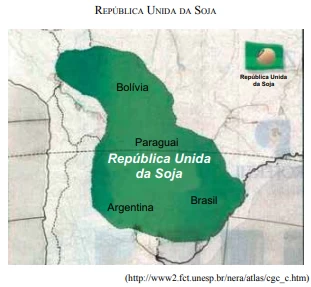

A questão está relacionada ao mapa apresentado a seguir - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014A questão está relacionada ao mapa apresentado a seguir.

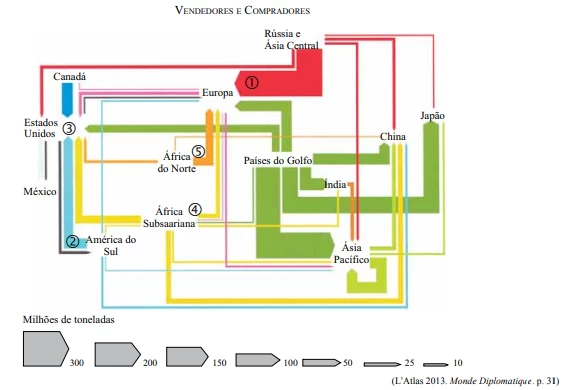

Os fluxos na figura identificam a circulação de um produto - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014Analise a figura a seguir.

[Na Amazônia] boa parte dos municípios que compõe a “mancha - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014[Na Amazônia] boa parte dos municípios que compõe a “mancha pioneira” apresenta as maiores taxas de desmatamento do bioma amazônico nos últimos anos... e um expressivo e perverso processo de especulação fundiária, no qual a grilagem e a venda ilegal de terras (inclusive pela internet) é o seu principal artífice. [...] A rarefeita presença humana e os meios rudimentares de sobrevivência de boa parte da população local, desprovida de capital e de qualificação, levam à configuração de um espaço descontínuo.

A questão está relacionada ao mapa e ao texto apresentados - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014A questão está relacionada ao mapa e ao texto apresentados a seguir.

... é um complexo de vegetação heterogênea, um mosaico de cerrados, florestas e até mesmo caatinga. [...] Inúmeros programas nacionais e internacionais de proteção ao ambiente foram instaurados para defender esse ecossistema único, frágil e ameaçado, ao mesmo tempo pela pecuária extensiva, pela dispersão de mercúrio e pelos resíduos de pesticidas (utilizados pelos agricultores) carreados do planalto que o domina, e pela exploração de suas matas galeria, o que aumenta a erosão e a sedimentação.

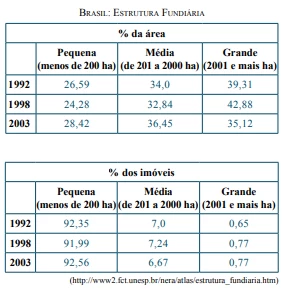

Considere as tabelas para responder à questão. Brasil: - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014Considere as tabelas para responder à questão.

Considere o texto. I. O inventário de emissão de gases de - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014Considere o texto.

I. O inventário de emissão de gases de efeito estufa de 2010, lançado em 2013 pelo Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação, mostra que houve a inversão do tipo de poluição predominante no Brasil em comparação ao relatório anterior, de 2004.

Baseados na análise de pesquisas e nos dados de várias Pnad - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014Baseados na análise de pesquisas e nos dados de várias Pnad (Pesquisa Nacional de Analise de Domicílios) sobre o mercado de trabalho nos últimos 20 anos, o Ipea (Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada) lançou, em outubro de 2013, um relatório com informações precisas sobre o trabalho no Brasil.

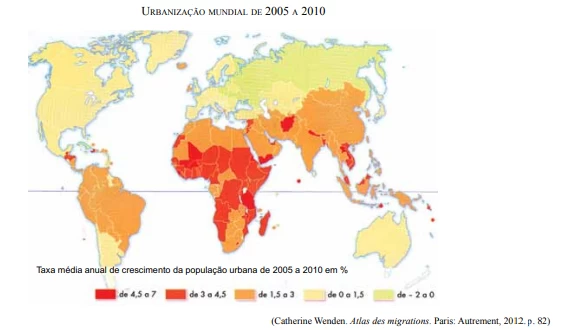

Ao se avaliarem as características da urbanização brasil - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014Ao se avaliarem as características da urbanização brasileira em seu período mais recente, é importante considerar os efeitos do processo de internacionalização da economia.[...] Uma das tendências desse processo é reforçar a localização de atividades nas cidades “da região mais desenvolvida do país, onde está localizada a maior parcela da base produtiva, que se moderniza mais rapidamente, e onde estão as melhores condições locacionais.”

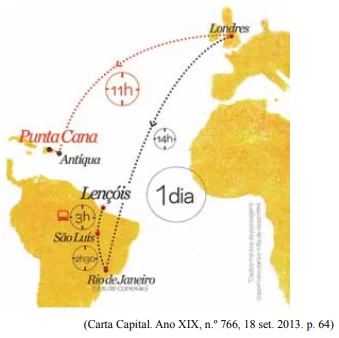

Um turista inglês tem duas possibilidades de viagem: Punta - FGV 2014

Geografia - 2014Um turista inglês tem duas possibilidades de viagem: Punta Cana ou Lençóis Maranhenses. Analise essas possibilidades apresentadas no mapa.

The core issue discussed in the article is: (A) Brazilian - FGV 2014

Inglês - 2014Read the article and answer the question

The road to hell

(1) Bringing crops from one of the futuristic new farms in Brazil’s central and northern plains to foreign markets means taking a journey back in time. Loaded onto lorries, most are driven almost 2,000km south on narrow, potholed roads to the ports of Santos and Paranaguá. In the 19th and early 20th centuries they were used to bring in immigrants and ship out the coffee grown in the fertile states of São Paulo and Paraná, but now they are overwhelmed. Thanks to a record harvest this year, Brazil became the world’s largest soya producer, overtaking the United States. The queue of lorries waiting to enter Santos sometimes stretched to 40km.

(2) No part of that journey makes sense. Brazil has too few crop silos, so lorries are used for storage as well as transport, causing a crush at ports after harvest. Produce from so far north should probably not be travelling to southern ports at all. Freight by road costs twice as much as by rail and four times as much as by water. Brazilian farmers pay 25% or more of the value of their soya to bring it to port; their competitors in Iowa just 9%. The bottleneck at ports pushes costs higher still. It also puts off customers. In March Sunrise Group, China’s biggest soya trader, cancelled an order for 2m tonnes of Brazilian soya after repeated delays.

(3) All of Brazil’s infrastructure is decrepit. The World Economic Forum ranks it at 114th out of 148 countries. After a spate of railway-building at the turn of the 20th century, and road- and dam-building 50 years later, little was added or even maintained. In the 1980s infrastructure was a casualty of slowing growth and spiralling inflation. Unable to find jobs, engineers emigrated or retrained. Government stopped planning for the long term. According to Contas Abertas, a public-spending watchdog, only a fifth of federal money budgeted for urban transport in the past decade was actually spent. Just 1.5% of Brazil’s GDP goes on infrastructure investment from all sources, both public and private. The long-run global average is 3.8%. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates the total value of Brazil’s infrastructure at 16% of GDP. Other big economies average 71%. To catch up, Brazil would have to triple its annual infrastructure spending for the next 20 years.

(4) Moreover, it may be getting poor value from what little it does invest because so much goes on the wrong things. A cumbersome environmental-licensing process pushes up costs and causes delays. Expensive studies are required before construction on big projects can start and then again at various stages along the way and at the end. Farmers and manufacturers spend heavily on lorries because road transport is their only option. But that is working around the problem, not solving it.

(5) In the 1990s Mr Cardoso’s government privatised state-owned oil, energy and telecoms firms. It allowed private operators to lease terminals in public ports and to build their own new ports. Imports were booming as the economy opened up, so container terminals were a priority. The one at the public port in Bahia’s capital, Salvador, is an example of the transformation wrought by private money and management. Its customers used to rate it Brazil’s worst port, with a draft too shallow for big ships and a quay so short that even smaller vessels had to unload a bit at a time. But in the past decade its operator, Wilson & Sons, spent 260m reais on replacing equipment, lengthening the quay and deepening the draft. Capacity has doubled. Land access will improve, too, once an almost finished expressway opens. Paranaguá is spending 400m reais from its own revenues on replacing outdated equipment, but without private money it cannot expand enough to end the queues to dock. It has drawn up detailed plans to build a new terminal and two new quays, and identified 20 dockside areas that could be leased to new operators, which would bring in 1.6 billion reais of private investment. All that is missing is the federal government’s permission. It hopes to get it next year, but there is no guarantee.

(6) Firms that want to build their own infrastructure, such as mining companies, which need dedicated railways and ports, can generally build at will in Brazil, though they still face the hassle of environmental licensing. If the government wants to hand a project to the private sector it will hold an auction, granting the concession to the highest bidder, or sometimes the applicant who promises the lowest user charges. But since Lula came to power in 2003 there have been few infrastructure auctions of any kind. In recent years, under heavy lobbying from public ports, the ports regulator stopped granting operating licences to private ports except those intended mainly for the owners’ own cargo. As a result, during a decade in which Brazil became a commodity-exporting powerhouse, its bulk-cargo terminals hardly expanded at all.

(7) At first Lula’s government planned to upgrade Brazil’s infrastructure without private help. In 2007 the president announced a collection of long-mooted public construction projects, the Growth Acceleration Programme (PAC). Many were intended to give farming and mining regions access to alternative ports. But the results have been disappointing. Two-thirds of the biggest projects are late and over budget. The trans-north-eastern railway is only half-built and its cost has doubled. The route of the east-west integration railway, which would cross Bahia, has still not been settled. The northern stretch of the BR-163, a trunk road built in the 1970s, was waiting so long to be paved that locals started calling it the “endless road”. Most of it is still waiting.

(8) What has got things moving is the prospect of disgrace during the forthcoming big sporting events. Brazil’s terrible airports will be the first thing most foreign football fans see when they arrive for next year’s World Cup. Infraero, the state-owned company that runs them, was meant to be getting them ready for the extra traffic, but it is a byword for incompetence. Between 2007 and 2010 it managed to spend just 800m of the 3 billion reais it was supposed to invest. In desperation, the government last year leased three of the biggest airports to private operators.

(9) That seemed to break a bigger logjam. First more airport auctions were mooted; then, some months later, Ms Rousseff announced that 7,500km of toll roads and 10,000km of railways were to be auctioned too. Earlier this year she picked the biggest fight of her presidency, pushing a ports bill through Congress against lobbying from powerful vested interests. The new law enables private ports once again to handle third-party cargo and allows them to hire their own staff, rather than having to use casual labour from the dockworkers’ unions that have a monopoly in public ports. Ms Rousseff also promised to auction some entirely new projects and to re-tender around 150 contracts in public terminals whose concessions had expired.

(10) Would-be investors in port projects are hanging back because of the high chances of cost overruns and long delays. Two newly built private terminals at Santos that together cost more than 4 billion reais illustrate the risks. Both took years to get off the ground and years more to build. Both were finished earlier this year but remained idle for months. Brasil Terminal Portuário, a private terminal within the public port, is still waiting for the government to dredge its access channel. At Embraport, which is outside the public-port area, union members from Santos blocked road access and boarded any ships that tried to dock. Rather than enforcing the law that allows such terminals to use their own workers, the government summoned the management to Brasília for some arm-twisting. In August Embraport agreed to take the union members “on a trial basis”.

(11) Given such regulatory and execution risks, there are unlikely to be many takers for either rail or port projects as currently conceived, says Bruno Savaris, an infrastructure analyst at Credit Suisse. He predicts that at most a third of the planned investments will be auctioned in the next three years: airports, a few simple port projects and the best toll roads. That is far short of what Brazil needs. The good news, says Mr Savaris, is that the government is at last beginning to understand that it must either reduce the risks for private investors or raise their returns. Private know-how and money will be vital to get Brazil moving again.

(www.economist.com/news/special-report. Adapted)

The metaphor developed in the first paragraph – a journey - FGV 2014

Inglês - 2014Read the article and answer the question

The road to hell

(1) Bringing crops from one of the futuristic new farms in Brazil’s central and northern plains to foreign markets means taking a journey back in time. Loaded onto lorries, most are driven almost 2,000km south on narrow, potholed roads to the ports of Santos and Paranaguá. In the 19th and early 20th centuries they were used to bring in immigrants and ship out the coffee grown in the fertile states of São Paulo and Paraná, but now they are overwhelmed. Thanks to a record harvest this year, Brazil became the world’s largest soya producer, overtaking the United States. The queue of lorries waiting to enter Santos sometimes stretched to 40km.

(2) No part of that journey makes sense. Brazil has too few crop silos, so lorries are used for storage as well as transport, causing a crush at ports after harvest. Produce from so far north should probably not be travelling to southern ports at all. Freight by road costs twice as much as by rail and four times as much as by water. Brazilian farmers pay 25% or more of the value of their soya to bring it to port; their competitors in Iowa just 9%. The bottleneck at ports pushes costs higher still. It also puts off customers. In March Sunrise Group, China’s biggest soya trader, cancelled an order for 2m tonnes of Brazilian soya after repeated delays.

(3) All of Brazil’s infrastructure is decrepit. The World Economic Forum ranks it at 114th out of 148 countries. After a spate of railway-building at the turn of the 20th century, and road- and dam-building 50 years later, little was added or even maintained. In the 1980s infrastructure was a casualty of slowing growth and spiralling inflation. Unable to find jobs, engineers emigrated or retrained. Government stopped planning for the long term. According to Contas Abertas, a public-spending watchdog, only a fifth of federal money budgeted for urban transport in the past decade was actually spent. Just 1.5% of Brazil’s GDP goes on infrastructure investment from all sources, both public and private. The long-run global average is 3.8%. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates the total value of Brazil’s infrastructure at 16% of GDP. Other big economies average 71%. To catch up, Brazil would have to triple its annual infrastructure spending for the next 20 years.

(4) Moreover, it may be getting poor value from what little it does invest because so much goes on the wrong things. A cumbersome environmental-licensing process pushes up costs and causes delays. Expensive studies are required before construction on big projects can start and then again at various stages along the way and at the end. Farmers and manufacturers spend heavily on lorries because road transport is their only option. But that is working around the problem, not solving it.

(5) In the 1990s Mr Cardoso’s government privatised state-owned oil, energy and telecoms firms. It allowed private operators to lease terminals in public ports and to build their own new ports. Imports were booming as the economy opened up, so container terminals were a priority. The one at the public port in Bahia’s capital, Salvador, is an example of the transformation wrought by private money and management. Its customers used to rate it Brazil’s worst port, with a draft too shallow for big ships and a quay so short that even smaller vessels had to unload a bit at a time. But in the past decade its operator, Wilson & Sons, spent 260m reais on replacing equipment, lengthening the quay and deepening the draft. Capacity has doubled. Land access will improve, too, once an almost finished expressway opens. Paranaguá is spending 400m reais from its own revenues on replacing outdated equipment, but without private money it cannot expand enough to end the queues to dock. It has drawn up detailed plans to build a new terminal and two new quays, and identified 20 dockside areas that could be leased to new operators, which would bring in 1.6 billion reais of private investment. All that is missing is the federal government’s permission. It hopes to get it next year, but there is no guarantee.

(6) Firms that want to build their own infrastructure, such as mining companies, which need dedicated railways and ports, can generally build at will in Brazil, though they still face the hassle of environmental licensing. If the government wants to hand a project to the private sector it will hold an auction, granting the concession to the highest bidder, or sometimes the applicant who promises the lowest user charges. But since Lula came to power in 2003 there have been few infrastructure auctions of any kind. In recent years, under heavy lobbying from public ports, the ports regulator stopped granting operating licences to private ports except those intended mainly for the owners’ own cargo. As a result, during a decade in which Brazil became a commodity-exporting powerhouse, its bulk-cargo terminals hardly expanded at all.

(7) At first Lula’s government planned to upgrade Brazil’s infrastructure without private help. In 2007 the president announced a collection of long-mooted public construction projects, the Growth Acceleration Programme (PAC). Many were intended to give farming and mining regions access to alternative ports. But the results have been disappointing. Two-thirds of the biggest projects are late and over budget. The trans-north-eastern railway is only half-built and its cost has doubled. The route of the east-west integration railway, which would cross Bahia, has still not been settled. The northern stretch of the BR-163, a trunk road built in the 1970s, was waiting so long to be paved that locals started calling it the “endless road”. Most of it is still waiting.

(8) What has got things moving is the prospect of disgrace during the forthcoming big sporting events. Brazil’s terrible airports will be the first thing most foreign football fans see when they arrive for next year’s World Cup. Infraero, the state-owned company that runs them, was meant to be getting them ready for the extra traffic, but it is a byword for incompetence. Between 2007 and 2010 it managed to spend just 800m of the 3 billion reais it was supposed to invest. In desperation, the government last year leased three of the biggest airports to private operators.

(9) That seemed to break a bigger logjam. First more airport auctions were mooted; then, some months later, Ms Rousseff announced that 7,500km of toll roads and 10,000km of railways were to be auctioned too. Earlier this year she picked the biggest fight of her presidency, pushing a ports bill through Congress against lobbying from powerful vested interests. The new law enables private ports once again to handle third-party cargo and allows them to hire their own staff, rather than having to use casual labour from the dockworkers’ unions that have a monopoly in public ports. Ms Rousseff also promised to auction some entirely new projects and to re-tender around 150 contracts in public terminals whose concessions had expired.

(10) Would-be investors in port projects are hanging back because of the high chances of cost overruns and long delays. Two newly built private terminals at Santos that together cost more than 4 billion reais illustrate the risks. Both took years to get off the ground and years more to build. Both were finished earlier this year but remained idle for months. Brasil Terminal Portuário, a private terminal within the public port, is still waiting for the government to dredge its access channel. At Embraport, which is outside the public-port area, union members from Santos blocked road access and boarded any ships that tried to dock. Rather than enforcing the law that allows such terminals to use their own workers, the government summoned the management to Brasília for some arm-twisting. In August Embraport agreed to take the union members “on a trial basis”.

(11) Given such regulatory and execution risks, there are unlikely to be many takers for either rail or port projects as currently conceived, says Bruno Savaris, an infrastructure analyst at Credit Suisse. He predicts that at most a third of the planned investments will be auctioned in the next three years: airports, a few simple port projects and the best toll roads. That is far short of what Brazil needs. The good news, says Mr Savaris, is that the government is at last beginning to understand that it must either reduce the risks for private investors or raise their returns. Private know-how and money will be vital to get Brazil moving again.

(www.economist.com/news/special-report. Adapted)

Expressions used in the article such as – cumbersome - FGV 2014

Inglês - 2014Read the article and answer the question

The road to hell

(1) Bringing crops from one of the futuristic new farms in Brazil’s central and northern plains to foreign markets means taking a journey back in time. Loaded onto lorries, most are driven almost 2,000km south on narrow, potholed roads to the ports of Santos and Paranaguá. In the 19th and early 20th centuries they were used to bring in immigrants and ship out the coffee grown in the fertile states of São Paulo and Paraná, but now they are overwhelmed. Thanks to a record harvest this year, Brazil became the world’s largest soya producer, overtaking the United States. The queue of lorries waiting to enter Santos sometimes stretched to 40km.

(2) No part of that journey makes sense. Brazil has too few crop silos, so lorries are used for storage as well as transport, causing a crush at ports after harvest. Produce from so far north should probably not be travelling to southern ports at all. Freight by road costs twice as much as by rail and four times as much as by water. Brazilian farmers pay 25% or more of the value of their soya to bring it to port; their competitors in Iowa just 9%. The bottleneck at ports pushes costs higher still. It also puts off customers. In March Sunrise Group, China’s biggest soya trader, cancelled an order for 2m tonnes of Brazilian soya after repeated delays.

(3) All of Brazil’s infrastructure is decrepit. The World Economic Forum ranks it at 114th out of 148 countries. After a spate of railway-building at the turn of the 20th century, and road- and dam-building 50 years later, little was added or even maintained. In the 1980s infrastructure was a casualty of slowing growth and spiralling inflation. Unable to find jobs, engineers emigrated or retrained. Government stopped planning for the long term. According to Contas Abertas, a public-spending watchdog, only a fifth of federal money budgeted for urban transport in the past decade was actually spent. Just 1.5% of Brazil’s GDP goes on infrastructure investment from all sources, both public and private. The long-run global average is 3.8%. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates the total value of Brazil’s infrastructure at 16% of GDP. Other big economies average 71%. To catch up, Brazil would have to triple its annual infrastructure spending for the next 20 years.

(4) Moreover, it may be getting poor value from what little it does invest because so much goes on the wrong things. A cumbersome environmental-licensing process pushes up costs and causes delays. Expensive studies are required before construction on big projects can start and then again at various stages along the way and at the end. Farmers and manufacturers spend heavily on lorries because road transport is their only option. But that is working around the problem, not solving it.

(5) In the 1990s Mr Cardoso’s government privatised state-owned oil, energy and telecoms firms. It allowed private operators to lease terminals in public ports and to build their own new ports. Imports were booming as the economy opened up, so container terminals were a priority. The one at the public port in Bahia’s capital, Salvador, is an example of the transformation wrought by private money and management. Its customers used to rate it Brazil’s worst port, with a draft too shallow for big ships and a quay so short that even smaller vessels had to unload a bit at a time. But in the past decade its operator, Wilson & Sons, spent 260m reais on replacing equipment, lengthening the quay and deepening the draft. Capacity has doubled. Land access will improve, too, once an almost finished expressway opens. Paranaguá is spending 400m reais from its own revenues on replacing outdated equipment, but without private money it cannot expand enough to end the queues to dock. It has drawn up detailed plans to build a new terminal and two new quays, and identified 20 dockside areas that could be leased to new operators, which would bring in 1.6 billion reais of private investment. All that is missing is the federal government’s permission. It hopes to get it next year, but there is no guarantee.

(6) Firms that want to build their own infrastructure, such as mining companies, which need dedicated railways and ports, can generally build at will in Brazil, though they still face the hassle of environmental licensing. If the government wants to hand a project to the private sector it will hold an auction, granting the concession to the highest bidder, or sometimes the applicant who promises the lowest user charges. But since Lula came to power in 2003 there have been few infrastructure auctions of any kind. In recent years, under heavy lobbying from public ports, the ports regulator stopped granting operating licences to private ports except those intended mainly for the owners’ own cargo. As a result, during a decade in which Brazil became a commodity-exporting powerhouse, its bulk-cargo terminals hardly expanded at all.

(7) At first Lula’s government planned to upgrade Brazil’s infrastructure without private help. In 2007 the president announced a collection of long-mooted public construction projects, the Growth Acceleration Programme (PAC). Many were intended to give farming and mining regions access to alternative ports. But the results have been disappointing. Two-thirds of the biggest projects are late and over budget. The trans-north-eastern railway is only half-built and its cost has doubled. The route of the east-west integration railway, which would cross Bahia, has still not been settled. The northern stretch of the BR-163, a trunk road built in the 1970s, was waiting so long to be paved that locals started calling it the “endless road”. Most of it is still waiting.

(8) What has got things moving is the prospect of disgrace during the forthcoming big sporting events. Brazil’s terrible airports will be the first thing most foreign football fans see when they arrive for next year’s World Cup. Infraero, the state-owned company that runs them, was meant to be getting them ready for the extra traffic, but it is a byword for incompetence. Between 2007 and 2010 it managed to spend just 800m of the 3 billion reais it was supposed to invest. In desperation, the government last year leased three of the biggest airports to private operators.

(9) That seemed to break a bigger logjam. First more airport auctions were mooted; then, some months later, Ms Rousseff announced that 7,500km of toll roads and 10,000km of railways were to be auctioned too. Earlier this year she picked the biggest fight of her presidency, pushing a ports bill through Congress against lobbying from powerful vested interests. The new law enables private ports once again to handle third-party cargo and allows them to hire their own staff, rather than having to use casual labour from the dockworkers’ unions that have a monopoly in public ports. Ms Rousseff also promised to auction some entirely new projects and to re-tender around 150 contracts in public terminals whose concessions had expired.

(10) Would-be investors in port projects are hanging back because of the high chances of cost overruns and long delays. Two newly built private terminals at Santos that together cost more than 4 billion reais illustrate the risks. Both took years to get off the ground and years more to build. Both were finished earlier this year but remained idle for months. Brasil Terminal Portuário, a private terminal within the public port, is still waiting for the government to dredge its access channel. At Embraport, which is outside the public-port area, union members from Santos blocked road access and boarded any ships that tried to dock. Rather than enforcing the law that allows such terminals to use their own workers, the government summoned the management to Brasília for some arm-twisting. In August Embraport agreed to take the union members “on a trial basis”.

(11) Given such regulatory and execution risks, there are unlikely to be many takers for either rail or port projects as currently conceived, says Bruno Savaris, an infrastructure analyst at Credit Suisse. He predicts that at most a third of the planned investments will be auctioned in the next three years: airports, a few simple port projects and the best toll roads. That is far short of what Brazil needs. The good news, says Mr Savaris, is that the government is at last beginning to understand that it must either reduce the risks for private investors or raise their returns. Private know-how and money will be vital to get Brazil moving again.

(www.economist.com/news/special-report. Adapted)

The second paragraph indicates that the Chinese business - FGV 2014

Inglês - 2014Read the article and answer the question

The road to hell

(1) Bringing crops from one of the futuristic new farms in Brazil’s central and northern plains to foreign markets means taking a journey back in time. Loaded onto lorries, most are driven almost 2,000km south on narrow, potholed roads to the ports of Santos and Paranaguá. In the 19th and early 20th centuries they were used to bring in immigrants and ship out the coffee grown in the fertile states of São Paulo and Paraná, but now they are overwhelmed. Thanks to a record harvest this year, Brazil became the world’s largest soya producer, overtaking the United States. The queue of lorries waiting to enter Santos sometimes stretched to 40km.

(2) No part of that journey makes sense. Brazil has too few crop silos, so lorries are used for storage as well as transport, causing a crush at ports after harvest. Produce from so far north should probably not be travelling to southern ports at all. Freight by road costs twice as much as by rail and four times as much as by water. Brazilian farmers pay 25% or more of the value of their soya to bring it to port; their competitors in Iowa just 9%. The bottleneck at ports pushes costs higher still. It also puts off customers. In March Sunrise Group, China’s biggest soya trader, cancelled an order for 2m tonnes of Brazilian soya after repeated delays.

(3) All of Brazil’s infrastructure is decrepit. The World Economic Forum ranks it at 114th out of 148 countries. After a spate of railway-building at the turn of the 20th century, and road- and dam-building 50 years later, little was added or even maintained. In the 1980s infrastructure was a casualty of slowing growth and spiralling inflation. Unable to find jobs, engineers emigrated or retrained. Government stopped planning for the long term. According to Contas Abertas, a public-spending watchdog, only a fifth of federal money budgeted for urban transport in the past decade was actually spent. Just 1.5% of Brazil’s GDP goes on infrastructure investment from all sources, both public and private. The long-run global average is 3.8%. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates the total value of Brazil’s infrastructure at 16% of GDP. Other big economies average 71%. To catch up, Brazil would have to triple its annual infrastructure spending for the next 20 years.

(4) Moreover, it may be getting poor value from what little it does invest because so much goes on the wrong things. A cumbersome environmental-licensing process pushes up costs and causes delays. Expensive studies are required before construction on big projects can start and then again at various stages along the way and at the end. Farmers and manufacturers spend heavily on lorries because road transport is their only option. But that is working around the problem, not solving it.

(5) In the 1990s Mr Cardoso’s government privatised state-owned oil, energy and telecoms firms. It allowed private operators to lease terminals in public ports and to build their own new ports. Imports were booming as the economy opened up, so container terminals were a priority. The one at the public port in Bahia’s capital, Salvador, is an example of the transformation wrought by private money and management. Its customers used to rate it Brazil’s worst port, with a draft too shallow for big ships and a quay so short that even smaller vessels had to unload a bit at a time. But in the past decade its operator, Wilson & Sons, spent 260m reais on replacing equipment, lengthening the quay and deepening the draft. Capacity has doubled. Land access will improve, too, once an almost finished expressway opens. Paranaguá is spending 400m reais from its own revenues on replacing outdated equipment, but without private money it cannot expand enough to end the queues to dock. It has drawn up detailed plans to build a new terminal and two new quays, and identified 20 dockside areas that could be leased to new operators, which would bring in 1.6 billion reais of private investment. All that is missing is the federal government’s permission. It hopes to get it next year, but there is no guarantee.

(6) Firms that want to build their own infrastructure, such as mining companies, which need dedicated railways and ports, can generally build at will in Brazil, though they still face the hassle of environmental licensing. If the government wants to hand a project to the private sector it will hold an auction, granting the concession to the highest bidder, or sometimes the applicant who promises the lowest user charges. But since Lula came to power in 2003 there have been few infrastructure auctions of any kind. In recent years, under heavy lobbying from public ports, the ports regulator stopped granting operating licences to private ports except those intended mainly for the owners’ own cargo. As a result, during a decade in which Brazil became a commodity-exporting powerhouse, its bulk-cargo terminals hardly expanded at all.

(7) At first Lula’s government planned to upgrade Brazil’s infrastructure without private help. In 2007 the president announced a collection of long-mooted public construction projects, the Growth Acceleration Programme (PAC). Many were intended to give farming and mining regions access to alternative ports. But the results have been disappointing. Two-thirds of the biggest projects are late and over budget. The trans-north-eastern railway is only half-built and its cost has doubled. The route of the east-west integration railway, which would cross Bahia, has still not been settled. The northern stretch of the BR-163, a trunk road built in the 1970s, was waiting so long to be paved that locals started calling it the “endless road”. Most of it is still waiting.

(8) What has got things moving is the prospect of disgrace during the forthcoming big sporting events. Brazil’s terrible airports will be the first thing most foreign football fans see when they arrive for next year’s World Cup. Infraero, the state-owned company that runs them, was meant to be getting them ready for the extra traffic, but it is a byword for incompetence. Between 2007 and 2010 it managed to spend just 800m of the 3 billion reais it was supposed to invest. In desperation, the government last year leased three of the biggest airports to private operators.

(9) That seemed to break a bigger logjam. First more airport auctions were mooted; then, some months later, Ms Rousseff announced that 7,500km of toll roads and 10,000km of railways were to be auctioned too. Earlier this year she picked the biggest fight of her presidency, pushing a ports bill through Congress against lobbying from powerful vested interests. The new law enables private ports once again to handle third-party cargo and allows them to hire their own staff, rather than having to use casual labour from the dockworkers’ unions that have a monopoly in public ports. Ms Rousseff also promised to auction some entirely new projects and to re-tender around 150 contracts in public terminals whose concessions had expired.

(10) Would-be investors in port projects are hanging back because of the high chances of cost overruns and long delays. Two newly built private terminals at Santos that together cost more than 4 billion reais illustrate the risks. Both took years to get off the ground and years more to build. Both were finished earlier this year but remained idle for months. Brasil Terminal Portuário, a private terminal within the public port, is still waiting for the government to dredge its access channel. At Embraport, which is outside the public-port area, union members from Santos blocked road access and boarded any ships that tried to dock. Rather than enforcing the law that allows such terminals to use their own workers, the government summoned the management to Brasília for some arm-twisting. In August Embraport agreed to take the union members “on a trial basis”.

(11) Given such regulatory and execution risks, there are unlikely to be many takers for either rail or port projects as currently conceived, says Bruno Savaris, an infrastructure analyst at Credit Suisse. He predicts that at most a third of the planned investments will be auctioned in the next three years: airports, a few simple port projects and the best toll roads. That is far short of what Brazil needs. The good news, says Mr Savaris, is that the government is at last beginning to understand that it must either reduce the risks for private investors or raise their returns. Private know-how and money will be vital to get Brazil moving again.

(www.economist.com/news/special-report. Adapted)

According to the third paragraph, (A) since the 1980s - FGV 2014

Inglês - 2014Read the article and answer the question

The road to hell

(1) Bringing crops from one of the futuristic new farms in Brazil’s central and northern plains to foreign markets means taking a journey back in time. Loaded onto lorries, most are driven almost 2,000km south on narrow, potholed roads to the ports of Santos and Paranaguá. In the 19th and early 20th centuries they were used to bring in immigrants and ship out the coffee grown in the fertile states of São Paulo and Paraná, but now they are overwhelmed. Thanks to a record harvest this year, Brazil became the world’s largest soya producer, overtaking the United States. The queue of lorries waiting to enter Santos sometimes stretched to 40km.

(2) No part of that journey makes sense. Brazil has too few crop silos, so lorries are used for storage as well as transport, causing a crush at ports after harvest. Produce from so far north should probably not be travelling to southern ports at all. Freight by road costs twice as much as by rail and four times as much as by water. Brazilian farmers pay 25% or more of the value of their soya to bring it to port; their competitors in Iowa just 9%. The bottleneck at ports pushes costs higher still. It also puts off customers. In March Sunrise Group, China’s biggest soya trader, cancelled an order for 2m tonnes of Brazilian soya after repeated delays.

(3) All of Brazil’s infrastructure is decrepit. The World Economic Forum ranks it at 114th out of 148 countries. After a spate of railway-building at the turn of the 20th century, and road- and dam-building 50 years later, little was added or even maintained. In the 1980s infrastructure was a casualty of slowing growth and spiralling inflation. Unable to find jobs, engineers emigrated or retrained. Government stopped planning for the long term. According to Contas Abertas, a public-spending watchdog, only a fifth of federal money budgeted for urban transport in the past decade was actually spent. Just 1.5% of Brazil’s GDP goes on infrastructure investment from all sources, both public and private. The long-run global average is 3.8%. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates the total value of Brazil’s infrastructure at 16% of GDP. Other big economies average 71%. To catch up, Brazil would have to triple its annual infrastructure spending for the next 20 years.

(4) Moreover, it may be getting poor value from what little it does invest because so much goes on the wrong things. A cumbersome environmental-licensing process pushes up costs and causes delays. Expensive studies are required before construction on big projects can start and then again at various stages along the way and at the end. Farmers and manufacturers spend heavily on lorries because road transport is their only option. But that is working around the problem, not solving it.

(5) In the 1990s Mr Cardoso’s government privatised state-owned oil, energy and telecoms firms. It allowed private operators to lease terminals in public ports and to build their own new ports. Imports were booming as the economy opened up, so container terminals were a priority. The one at the public port in Bahia’s capital, Salvador, is an example of the transformation wrought by private money and management. Its customers used to rate it Brazil’s worst port, with a draft too shallow for big ships and a quay so short that even smaller vessels had to unload a bit at a time. But in the past decade its operator, Wilson & Sons, spent 260m reais on replacing equipment, lengthening the quay and deepening the draft. Capacity has doubled. Land access will improve, too, once an almost finished expressway opens. Paranaguá is spending 400m reais from its own revenues on replacing outdated equipment, but without private money it cannot expand enough to end the queues to dock. It has drawn up detailed plans to build a new terminal and two new quays, and identified 20 dockside areas that could be leased to new operators, which would bring in 1.6 billion reais of private investment. All that is missing is the federal government’s permission. It hopes to get it next year, but there is no guarantee.

(6) Firms that want to build their own infrastructure, such as mining companies, which need dedicated railways and ports, can generally build at will in Brazil, though they still face the hassle of environmental licensing. If the government wants to hand a project to the private sector it will hold an auction, granting the concession to the highest bidder, or sometimes the applicant who promises the lowest user charges. But since Lula came to power in 2003 there have been few infrastructure auctions of any kind. In recent years, under heavy lobbying from public ports, the ports regulator stopped granting operating licences to private ports except those intended mainly for the owners’ own cargo. As a result, during a decade in which Brazil became a commodity-exporting powerhouse, its bulk-cargo terminals hardly expanded at all.

(7) At first Lula’s government planned to upgrade Brazil’s infrastructure without private help. In 2007 the president announced a collection of long-mooted public construction projects, the Growth Acceleration Programme (PAC). Many were intended to give farming and mining regions access to alternative ports. But the results have been disappointing. Two-thirds of the biggest projects are late and over budget. The trans-north-eastern railway is only half-built and its cost has doubled. The route of the east-west integration railway, which would cross Bahia, has still not been settled. The northern stretch of the BR-163, a trunk road built in the 1970s, was waiting so long to be paved that locals started calling it the “endless road”. Most of it is still waiting.

(8) What has got things moving is the prospect of disgrace during the forthcoming big sporting events. Brazil’s terrible airports will be the first thing most foreign football fans see when they arrive for next year’s World Cup. Infraero, the state-owned company that runs them, was meant to be getting them ready for the extra traffic, but it is a byword for incompetence. Between 2007 and 2010 it managed to spend just 800m of the 3 billion reais it was supposed to invest. In desperation, the government last year leased three of the biggest airports to private operators.

(9) That seemed to break a bigger logjam. First more airport auctions were mooted; then, some months later, Ms Rousseff announced that 7,500km of toll roads and 10,000km of railways were to be auctioned too. Earlier this year she picked the biggest fight of her presidency, pushing a ports bill through Congress against lobbying from powerful vested interests. The new law enables private ports once again to handle third-party cargo and allows them to hire their own staff, rather than having to use casual labour from the dockworkers’ unions that have a monopoly in public ports. Ms Rousseff also promised to auction some entirely new projects and to re-tender around 150 contracts in public terminals whose concessions had expired.

(10) Would-be investors in port projects are hanging back because of the high chances of cost overruns and long delays. Two newly built private terminals at Santos that together cost more than 4 billion reais illustrate the risks. Both took years to get off the ground and years more to build. Both were finished earlier this year but remained idle for months. Brasil Terminal Portuário, a private terminal within the public port, is still waiting for the government to dredge its access channel. At Embraport, which is outside the public-port area, union members from Santos blocked road access and boarded any ships that tried to dock. Rather than enforcing the law that allows such terminals to use their own workers, the government summoned the management to Brasília for some arm-twisting. In August Embraport agreed to take the union members “on a trial basis”.

(11) Given such regulatory and execution risks, there are unlikely to be many takers for either rail or port projects as currently conceived, says Bruno Savaris, an infrastructure analyst at Credit Suisse. He predicts that at most a third of the planned investments will be auctioned in the next three years: airports, a few simple port projects and the best toll roads. That is far short of what Brazil needs. The good news, says Mr Savaris, is that the government is at last beginning to understand that it must either reduce the risks for private investors or raise their returns. Private know-how and money will be vital to get Brazil moving again.

(www.economist.com/news/special-report. Adapted)

The first word used in the fourth paragraph – moreover – - FGV 2014

Inglês - 2014Read the article and answer the question

The road to hell

(1) Bringing crops from one of the futuristic new farms in Brazil’s central and northern plains to foreign markets means taking a journey back in time. Loaded onto lorries, most are driven almost 2,000km south on narrow, potholed roads to the ports of Santos and Paranaguá. In the 19th and early 20th centuries they were used to bring in immigrants and ship out the coffee grown in the fertile states of São Paulo and Paraná, but now they are overwhelmed. Thanks to a record harvest this year, Brazil became the world’s largest soya producer, overtaking the United States. The queue of lorries waiting to enter Santos sometimes stretched to 40km.

(2) No part of that journey makes sense. Brazil has too few crop silos, so lorries are used for storage as well as transport, causing a crush at ports after harvest. Produce from so far north should probably not be travelling to southern ports at all. Freight by road costs twice as much as by rail and four times as much as by water. Brazilian farmers pay 25% or more of the value of their soya to bring it to port; their competitors in Iowa just 9%. The bottleneck at ports pushes costs higher still. It also puts off customers. In March Sunrise Group, China’s biggest soya trader, cancelled an order for 2m tonnes of Brazilian soya after repeated delays.

(3) All of Brazil’s infrastructure is decrepit. The World Economic Forum ranks it at 114th out of 148 countries. After a spate of railway-building at the turn of the 20th century, and road- and dam-building 50 years later, little was added or even maintained. In the 1980s infrastructure was a casualty of slowing growth and spiralling inflation. Unable to find jobs, engineers emigrated or retrained. Government stopped planning for the long term. According to Contas Abertas, a public-spending watchdog, only a fifth of federal money budgeted for urban transport in the past decade was actually spent. Just 1.5% of Brazil’s GDP goes on infrastructure investment from all sources, both public and private. The long-run global average is 3.8%. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates the total value of Brazil’s infrastructure at 16% of GDP. Other big economies average 71%. To catch up, Brazil would have to triple its annual infrastructure spending for the next 20 years.

(4) Moreover, it may be getting poor value from what little it does invest because so much goes on the wrong things. A cumbersome environmental-licensing process pushes up costs and causes delays. Expensive studies are required before construction on big projects can start and then again at various stages along the way and at the end. Farmers and manufacturers spend heavily on lorries because road transport is their only option. But that is working around the problem, not solving it.