FGV

Exibindo questões de 901 a 1000.

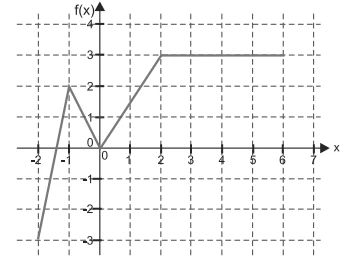

O gráfico representa a função Considerando –2 ≤ x ≤ 3, o con- FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015O gráfico representa a função f.

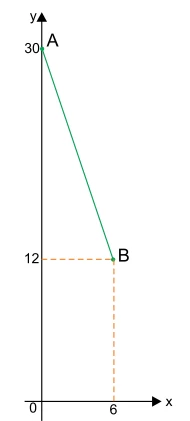

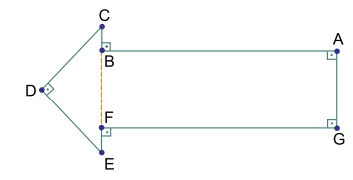

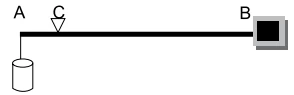

As coordenadas (x, y) de cada ponto do segmento AB, - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015As coordenadas (x, y) de cada ponto do segmento AB, descrito na figura, representam o comprimento (x) e a largura (y) de um retângulo, ambos em centímetros. Por exemplo, o ponto de coordenadas (4, 18) representa um retângulo de comprimento 4 cm e largura 18 cm.

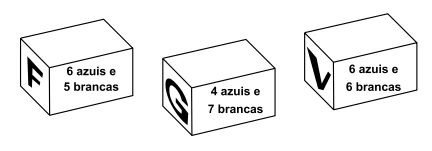

Conforme indica a figura, uma caixa contém 6 letras F azuis - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Conforme indica a figura, uma caixa contém 6 letras F azuis e 5 brancas, a outra contém 4 letras G azuis e 7 brancas, e a última caixa contém 6 letras V azuis e 6 brancas.

Um código numérico tem a forma ABC-DEF-GHIJ, sendo que cada - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Um código numérico tem a forma ABC-DEF-GHIJ, sendo que cada letra representa um algarismo diferente. Em cada uma das três partes do código, os algarismos estão em ordem decrescente, ou seja, A>B>C, D>E>F e G>H>I>J. Sabe-se ainda que D, E e F são números pares consecutivos, e que G, H, I e J são números ímpares consecutivos. Se A+B+C=17,

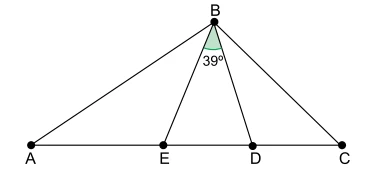

A figura representa um triângulo ABC, com E e D sendo - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015A figura representa um triângulo ABC, com E e D sendo pontos sobre — AC. Sabe-se ainda que AB = AD, CB = CE e que E^ BD mede 39°.

Dois dados convencionais e honestos são lançados - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Dois dados convencionais e honestos são lançados simultaneamente.

A raiz quadrada da diferença entre a dízima periódica 0,444 - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015A raiz quadrada da diferença entre a dízima periódica 0,444... e o decimal de representação finita

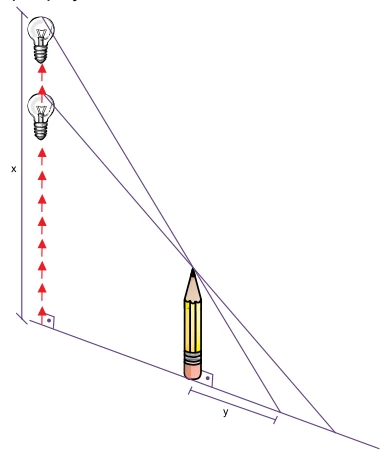

Um dispositivo fará com que uma lâmpada acesa se desloque - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Um dispositivo fará com que uma lâmpada acesa se desloque verticalmente em relação ao solo em x centímetros. Quando a lâmpada se desloca, o comprimento y, em cm, da sombra de um lápis, projetada no solo, também deverá variar.

Sueli colocou 40 mL de café em uma xícara vazia de 80 mL, - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Sueli colocou 40 mL de café em uma xícara vazia de 80 mL, e 40 mL de leite em outra xícara vazia de mesmo tamanho. Em seguida, Sueli transferiu metade do conteúdo da primeira xícara para a segunda e, depois de misturar bem, transferiu metade do novo conteúdo da segunda xícara de volta para a primeira.

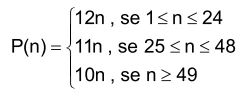

Uma editora tem preços promocionais de venda de um livro - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Uma editora tem preços promocionais de venda de um livro para escolas. A tabela de preços é:

onde n é a quantidade encomendada de livros, e P(n) o preço total dos n exemplares.

Observe as coordenadas cartesianas de cinco pontos: - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Observe as coordenadas cartesianas de cinco pontos: A(0,100), B(0, -100), C(10, 100), D(10, -100), E(100, 0). Se a reta de equação reduzida y = mx + n é tal que mn > 0, então, dos cinco pontos dados anteriormente,

Seja f:IR →IR, tal que , com b sendo uma constante real - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Seja f:IR →IR, tal que  com b sendo uma constante real positiva.

com b sendo uma constante real positiva.

Um envelope lacrado contém um cartão marcado com um único - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Um envelope lacrado contém um cartão marcado com um único dígito. A respeito desse dígito são feitas quatro afirmações, das quais apenas três são verdadeiras. As afirmações são:

I. O dígito é 1.

II. O dígito não é 2.

III. O dígito é 3.

IV. O dígito não é 4.

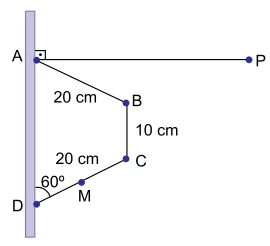

Na figura, ABCD representa uma placa em forma de trapézio - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Na figura, ABCD representa uma placa em forma de trapézio isósceles de ângulo da base medindo 60°. A placa está fixada em uma parede por AD, e PA representa uma corda perfeitamente esticada, inicialmente perpendicular à parede.

Determinada marca de ervilhas vende o produto em embalagens - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Determinada marca de ervilhas vende o produto em embalagens com a forma de cilindros circulares retos. Uma delas tem raio da base 4 cm. A outra, é uma ampliação perfeita da embalagem menor, com raio da base 5 cm. O preço do produto vendido na embalagem menor é de R$ 2,00. A embalagem maior dá um desconto, por mL de ervilha, de 10% em relação ao preço por mL de ervilha da embalagem menor.

O total de números pares não negativos de até quatro - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015O total de números pares não negativos de até quatro algarismos que podem ser formados com os algarismos 0, 1, 2 e 3,

Os elementos da matriz A = (aij) 3x3 representam a - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Os elementos da matriz A = (aij) 3x3 representam a quantidade de voos diários apenas entre os aeroportos i, de um país, e os aeroportos j, de outro país. A respeito desses voos, sabe- -se que:

quando j = 2, o número de voos é sempre o mesmo,

quando i = j, o número de voos é sempre o mesmo,

quando i = 3, o número de voos é sempre o mesmo;

a11 ≠ 0, e det A = 0.

Em uma sala estão presentes n pessoas, com n>3. Pelo menos - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Em uma sala estão presentes n pessoas, com n>3. Pelo menos uma pessoa da sala não trocou aperto de mão com todos os presentes na sala, e os demais presentes trocaram apertos de mão entre si, e um único aperto por dupla de pessoas.

Se x2 – x – 1 é um dos fatores da fatoração de mx3 + nx2 - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Se x2 – x – 1 é um dos fatores da fatoração de mx3 + nx2 + 1,

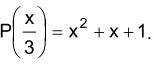

Considere o polinômio P(X) tal que . A soma de todas as - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Considere o polinômio P(X) tal que

A seta indica um heptágono com AB=GF=2AG=4BC=4FE=20 cm - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015A seta indica um heptágono com AB=GF=2AG=4BC=4FE=20 cm.

Se 1 + cos α + cos2 α + cos3 α + cos4 α + ... = 5, com , - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2015Se 1 + cos α + cos2 α + cos3 α + cos4 α + ... = 5, com

O mexilhão dourado, Limnoperna fortunei, é um bivalve - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015O mexilhão dourado, Limnoperna fortunei, é um bivalve originário da Ásia. A espécie chegou à América do Sul provavelmente de modo acidental na água de lastro de navios cargueiros.

Durante a fase larval, o bivalve é levado pela água até que termina por se alojar em superfícies sólidas, onde se fixa e cresce formando grandes colônias.

Podemos citar como prejuízos causados pelo mexilhão dourado: a destruição da vegetação aquática; a ocupação do espaço e a disputa por alimento com os moluscos nativos; o entupimento de canos e dutos de água para irrigação e geração de energia elétrica, dentre outros.

(http://www.ibama.gov.br. Adaptado)

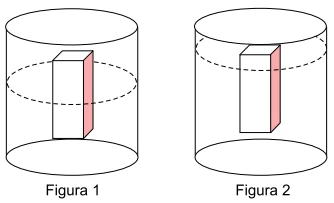

As figuras ilustram o processo de crossing-over, que ocorre - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015As figuras ilustram o processo de crossing-over, que ocorre na prófase I da meiose.

O vírus ebola, descoberto por microbiologistas em 1976, - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015O vírus ebola, descoberto por microbiologistas em 1976, causa em seres humanos grave febre hemorrágica. De acordo com o sistema de classificação de Baltimore, trata-se de um vírus pertencente ao grupo V, cujos integrantes apresentam RNA de fita simples, com senso negativo, como material genético. Essa fita necessita ser convertida pela enzima RNA polimerase, em uma fita de RNA com senso positivo, a qual pode então ser traduzida para a manifestação dos genes virais.

Alimentos como a mandioca, a batata e o arroz armazenam - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015Alimentos como a mandioca, a batata e o arroz armazenam grande quantidade de amido no parênquima amilífero. Já o parênquima clorofiliano é responsável pela síntese de glicose.

O pâncreas é uma glândula anfícrina, ou seja, com dupla - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015O pâncreas é uma glândula anfícrina, ou seja, com dupla função, desempenhando um papel junto ao sistema digestório na produção de enzimas, tais como amilases e lipases, e também junto ao sistema endócrino, na produção de hormônios, tais como a insulina e o glucagon.

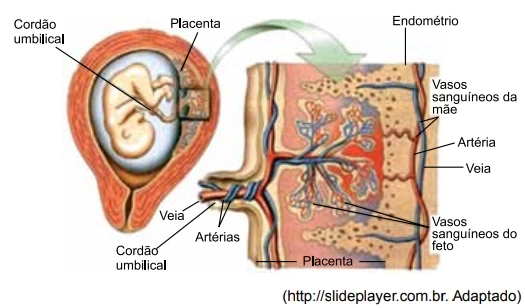

A figura ilustra os vasos sanguíneos maternos e fetais na - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015A figura ilustra os vasos sanguíneos maternos e fetais na região da placenta, responsável pela troca dos gases respiratórios oxigênio e dióxido de carbono.

Autotomia é a capacidade que alguns animais apresentam em - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015Autotomia é a capacidade que alguns animais apresentam em soltar membros do corpo e regenerá-los posteriormente, como por exemplo, a autotomia caudal observada em algumas espécies de lagartos, conforme mostra a figura.

Nem todos os tecidos se recompõem e a regeneração torna-se menos eficiente a cada perda da cauda, podendo inclusive não ocorrer, dependendo do local da mutilação.

Nem todos os tecidos se recompõem e a regeneração torna-se - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015Autotomia é a capacidade que alguns animais apresentam em soltar membros do corpo e regenerá-los posteriormente, como por exemplo, a autotomia caudal observada em algumas espécies de lagartos, conforme mostra a figura.

Nem todos os tecidos se recompõem e a regeneração torna-se menos eficiente a cada perda da cauda, podendo inclusive não ocorrer, dependendo do local da mutilação.

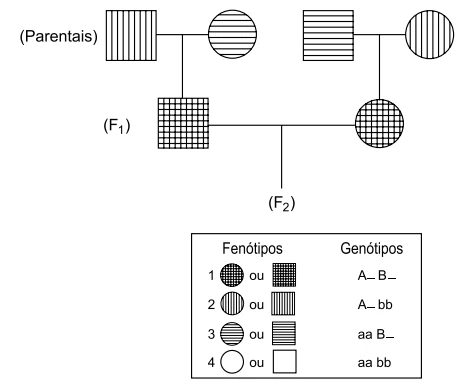

Analise o heredograma que ilustra a transmissão de duas - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015Analise o heredograma que ilustra a transmissão de duas características genéticas, cada uma condicionada por um par de alelos autossômicos com dominância simples.

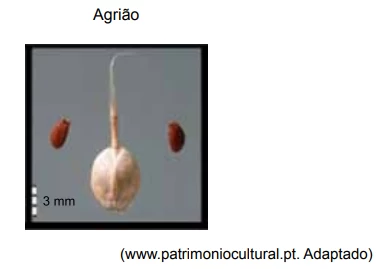

A figura ilustra sementes e fruto bastante pequenos do - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015A figura ilustra sementes e fruto bastante pequenos do agrião, uma hortaliça.

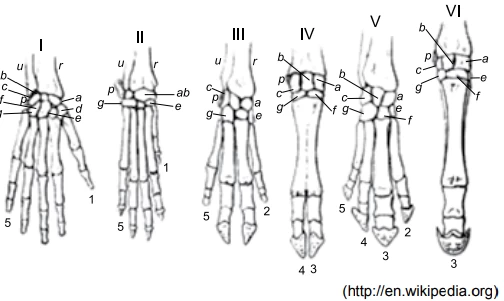

As estruturas ilustram os ossos das mãos ou patas - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015As estruturas ilustram os ossos das mãos ou patas anteriores de seis espécies de mamíferos, não pertencentes obrigatoriamente ao mesmo ecossistema.

A transformação evolutiva de tais estruturas, ao longo das gerações, ocorre em função __________ e indicam uma evidência evolutiva denominada __________.

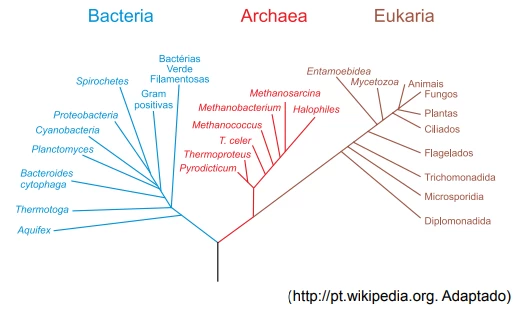

Carl Woese propôs, em 1990, uma nova classificação na qual - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015Carl Woese propôs, em 1990, uma nova classificação na qual os seres vivos são divididos em três domínios, sendo eles Bacteria, Archaea e Eukaria.

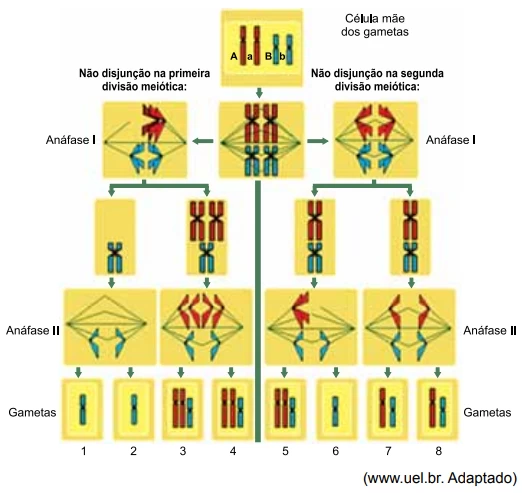

As células numeradas de 1 a 4 da figura representam gametas - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015As células numeradas de 1 a 4 da figura representam gametas masculinos resultantes de uma divisão meiótica anômala em que não ocorreu disjunção dos cromossomos homólogos vermelhos na anáfase I. As células numeradas de 5 a 8 da figura representam gametas masculinos resultantes de outra divisão meiótica anômala em que não ocorreu a disjunção das cromátides vermelhas na anáfase II. Os cromossomos azuis representam o processo sem anomalias em todos os demais pares de cromossomos humanos.

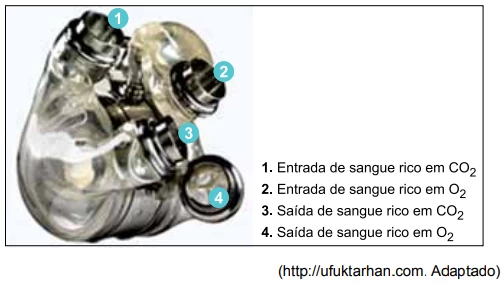

A figura ilustra um coração artificial mecânico, cujos - FGV 2015

Biologia - 2015A figura ilustra um coração artificial mecânico, cujos números indicam os orifícios para a entrada e saída do fluxo sanguíneo.

É a partir do século VIII a.C. que começamos a entrever, em - FGV 2015

História - 2015É a partir do século VIII a.C. que começamos a entrever, em diferentes regiões do Mediterrâneo, o progressivo surgimento das cidades-Estados ou pólis. Elas formaram a organização social e política dominante das comunidades organizadas ao longo do Mediterrâneo nos séculos seguintes.

(...) quais mecanismos levaram à escravidão nas sociedades - FGV 2015

História - 2015(...) quais mecanismos levaram à escravidão nas sociedades africanas do século VII ao século XV?

(...)

Genericamente, a escravidão esteve presente na África como um todo, fazendo-se necessário observar as especificidades históricas próprias de complexos sociais e políticos e das formas de poder das diversas sociedades africanas. Mas é fundamental acrescentar que a dinâmica e a intensidade da escravidão no continente africano tem a ver com a maior ou menor demanda do tráfico atlântico gerada pelo expansionismo europeu na América. Isso acarreta mudanças sociais na África, como a expansão e a subsequente transformação da poligenia, o desenvolvimento de diferentes tipos de escravidão no continente, além do empobrecimento de uma classe de mercadores africanos.

Leia o documento de 1346. (...) se qualquer pessoa do dito - FGV 2015

História - 2015Leia o documento de 1346.

(...) se qualquer pessoa do dito ofício sofrer de pobreza pela idade, ou porque não possa trabalhar terá toda semana 7 dinheiros para seu sustento (...)

E nenhum estrangeiro trabalhará no dito ofício se não for aprendiz, ou homem admitido à cidadania do dito lugar.

(...) E se alguém do dito ofício tiver em sua casa trabalho que não possa completar... os demais do mesmo ofício o ajudarão, para que o dito trabalho não se perca.

(...) Prestando perante eles o juramento de indagar e pesquisar (...) os erros que encontrarem no dito comércio, sem poupar ninguém, por amizade ou ódio.

Ninguém que não tenha sido aprendiz e não tenha concluído seu termo de aprendizado do dito ofício poderá exercer o mesmo.

O Estado era tanto o sujeito como o objeto da política - FGV 2015

História - 2015O Estado era tanto o sujeito como o objeto da política econômica mercantilista. O mercantilismo refletia a concepção a respeito das relações entre o Estado e a nação que imperava na época (séculos XVI e XVII). Era o Estado, não a nação, o que lhe interessava.

A interrupção desse fluxo comercial levaria os negociantes - FGV 2015

História - 2015A interrupção desse fluxo comercial levaria os negociantes e financistas da República a fundarem a Companhia das Índias Ocidentais (1621). (...)

O historiador Charles Boxer considera que esse conflito, por produtos e mercados, entre o Império Habsburgo e as Províncias Unidas, foi tão generalizado que pode ser considerado, de fato, a Primeira Guerra Mundial, pois atingiu os quatros cantos do mundo.

Caracteriza a agricultura colonial no Brasil do final do - FGV 2015

História - 2015Caracteriza a agricultura colonial no Brasil

É a América Latina, as regiões das veias abertas. Desde o - FGV 2015

História - 2015É a América Latina, as regiões das veias abertas. Desde o descobrimento até nossos dias, tudo se transformou em capital estrangeiro e como tal acumula-se até hoje. A causa nacional latino-americana é, antes de tudo, uma causa social.

Os dados do mapa mostram que a emancipação política do - FGV 2015

História - 2015Observe o mapa.

A unidade italiana – o processo de constituição de um - FGV 2015

História - 2015A unidade italiana – o processo de constituição de um Estado único para o país – conserva o sistema oligárquico (...) Isto não impede a formação do Estado, mas retarda a eclosão do fenômeno nacional.

(Leon Pomer, O surgimento das nações, 1985, p. 40-42)

Fizemos a Itália; agora, precisamos fazer os italianos.

Em nome do direito de viver da humanidade, a colonização, - FGV 2015

História - 2015Em nome do direito de viver da humanidade, a colonização, agente da civilização, deverá tomar a seu encargo a valorização e a circulação das riquezas que possuidores fracos detenham sem benefício para eles próprios e para os demais. Age-se, assim, para o bem de todos. (...) [A Europa] está no comando e no comando deve permanecer.

No livro de crônicas Cidades Mortas, o escritor Monteiro - FGV 2015

História - 2015No livro de crônicas Cidades Mortas, o escritor Monteiro Lobato descreve o destino de ricas cidades cafeicultoras do Vale do Paraíba. Bananal, que chegou a ser a maior produtora de café da província de São Paulo, tornou-se uma “cidade morta”, que vive do esplendor do passado: transformou-se em uma estância turístico-histórica, mantendo poucas sedes majestosas conservadas, como a da Fazenda Resgate. A maioria, entretanto, está em ruínas. O fim da escravidão foi o fim dos barões. E também o fim do Império.

Esses anos [pós-guerra] também foram notáveis sob outro - FGV 2015

História - 2015Esses anos [pós-guerra] também foram notáveis sob outro aspecto pois, à medida que o tempo passava, tornava-se evidente que aquela prosperidade não duraria. Dentro dela estavam contidas as sementes de sua própria destruição.

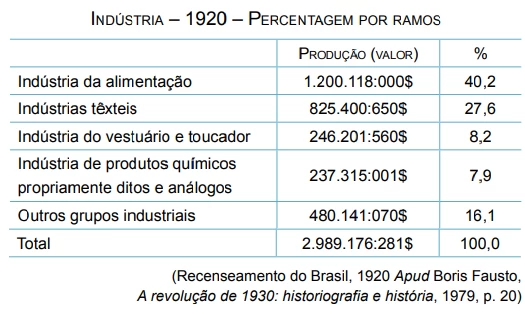

A partir dos dados, é correto afirmar que a indústria - FGV 2015

História - 2015Observe a tabela.

Leia um trecho de uma entrevista com o historiador - FGV 2015

História - 2015Leia um trecho de uma entrevista com o historiador Francisco Alembert.

(...) os governos vêm sucessivamente utilizando a retórica, a imagem e o mito do governo de Juscelino, por isso ele continua tão forte e tão presente. Mas há também algo em comum na utilização de JK por esses governos. De uma forma ou de outra, eles procuram justificar o crescimento econômico dentro da democracia. Ele agradava a burguesia, porque se mostrava um governo modernizador, e também agradava a esquerda, mesmo não tendo uma política de esquerda. Mas alcançou um crescimento realmente fantástico, nunca visto antes. O grande problema é que isso não foi dividido por toda a sociedade.

(...) dividamos a experiência (passeio na montanha-russa) - FGV 2015

História - 2015(...) dividamos a experiência (passeio na montanha-russa) em três partes. A primeira é a da ascensão contínua, metódica e persistente (...). Essa fase representa o período do século XVI até meados do século XIX, quando as elites da Europa promovem o desenvolvimento tecnológico que lhes asseguraria o domínio do mundo. A segunda nos precipita em uma queda vertiginosa, com a perda das referências do espaço, do que nos cerca e até o controle das faculdades conscientes (...). Isto ocorreu ao redor de 1870, com a chamada Revolução Científico-Tecnológico. (...) A terceira é a do loop, o clímax da aceleração precipitada, que representaria o atual período, assinalado por um novo surto dramático de transformações, a Revolução da Microeletrônica (...) o que faz os dois movimentos anteriores parecerem projeções em câmera lenta. (...) O aparato tecnológico torna-se cada vez mais imprevisível, irresistível e incompreensível.

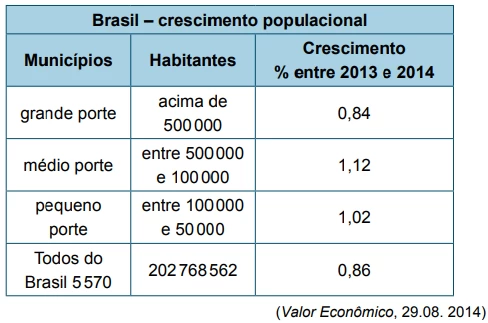

A população brasileira cresceu 0,86% entre 2013 e 2014, - FGV 2015

Geografia - 2015A população brasileira cresceu 0,86% entre 2013 e 2014, segundo o IBGE. O total de habitantes nos 5570 municípios do país chegou a 202768562 habitantes em julho de 2014, mas o percentual de crescimento não foi uniforme em todos eles.

A exploração do Pré-Sal poderá posicionar o Brasil como um - FGV 2015

Geografia - 2015A exploração do Pré-Sal poderá posicionar o Brasil como um dos maiores exportadores de petróleo do mundo, com um excedente na produção que poderá superar 1,5 milhão de barris por dia, em um momento em que a demanda pelo insumo não será mais liderada pelo país Estados Unidos, mas pela Ásia.

A matriz energética desse país é baseada em carvão mineral, - FGV 2015

Geografia - 2015A matriz energética desse país é baseada em carvão mineral, transportado por ferrovias, que usam muito diesel; o minério segue em navios, que consomem muito combustível, e o país ainda tem demanda grande de petroquímicos, por conta da construção civil e bens de consumo e da sua crescente urbanização. Em 2010, tornou-se o maior consumidor mundial de petróleo, ultrapassando os Estados Unidos. Em 2003, o valor das exportações de petróleo do Brasil para esse país era 0,5% do total, e, em 2013, as exportações brasileiras saltaram para 8,7%, confirmando a liderança comercial desse país com o Brasil.

Destaca-se na crescente exportação de frutas, - FGV 2015

Geografia - 2015Destaca-se na crescente exportação de frutas, principalmente uva, manga, goiaba e banana cultivadas com técnicas de irrigação. O dinamismo da economia estadual, principalmente no setor industrial, está associado a sua moderna infraestrutura portuária. Destaca-se, também, pela indústria têxtil e de confecções.

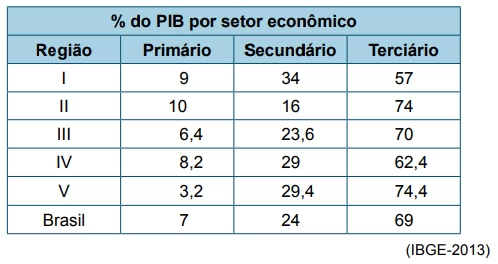

As regiões brasileiras apresentam nítida diferença na - FGV 2015

Geografia - 2015As regiões brasileiras apresentam nítida diferença na distribuição do PIB segundo os setores econômicos.

Analise a tabela a seguir.

Segundo um estudo realizado pela unidade de pesquisa da - FGV 2015

Geografia - 2015Segundo um estudo realizado pela unidade de pesquisa da revista britânica The Economist, tendo por base o desempenho dos 26 estados e do Distrito Federal em oito categorias e vinte e cinco indicadores, foi criado o mapa a seguir.

O Protocolo da Biodiversidade, considerado histórico na sua - FGV 2015

História - 2015O Protocolo da Biodiversidade, considerado histórico na sua criação, em 2010, na 10a . Convenção Mundial da Biodiversidade, em Nagoia, no Japão, objetiva garantir a divisão justa e equitativa de benefícios, gerados pelo uso dos recursos genéticos e da biodiversidade, combatendo a biopirataria, protegendo o patrimônio biológico dos países, por meio de instrumentos, como a criação de royalties para o uso da flora e da fauna locais.

Entrará em vigor após a ratificação por 50 países, e o Brasil, embora tenha assinado o documento da criação do protocolo, aguarda a ratificação pelo Congresso.

Em julho de 2014, foi criado, em Fortaleza (Brasil), o Novo - FGV 2015

Geografia - 2015Em julho de 2014, foi criado, em Fortaleza (Brasil), o Novo Banco de Desenvolvimento, idealizado para ser uma alternativa ao Banco Mundial. O banco terá capital de US$ 50 bilhões, que pode ser ampliado para US$ 100 bilhões, para financiar projetos de infraestrutura e sustentabilidade em países emergentes, sem se submeter às imposições dos países ricos do Banco Mundial da ONU.

Foi estabelecido, também, um Arranjo Contingente de Reservas, que funcionará como um fundo de emergência inicial de US$ 100 bilhões que pode ser sacado pelos países em épocas de crise no balanço de pagamentos. Todos os países do grupo assumirão a presidência do banco, obedecendo a rotatividade a cada cinco anos.

A construção do Grande Canal Interoceânico, na Nicarágua, - FGV 2015

Geografia - 2015A construção do Grande Canal Interoceânico, na Nicarágua, ligando os oceanos Atlântico e Pacífico, promete ser a maior rede de transporte hidroviário do hemisfério ocidental e poderá desafiar o controle dos EUA sobre a região. A nova hidrovia irá se estender por 286 km, contra os atuais 81,5 km do Canal do Panamá. A principal vantagem da rota é sua largura de 83 metros e a profundidade de 27,5 m, o que permitirá a navegação de embarcações de classe superpesada, com porte de até 270 mil toneladas.

Por meio das doze zonas francas, como a Zonamérica, o país - FGV 2015

Geografia - 2015Por meio das doze zonas francas, como a Zonamérica, o país ganhou competitividade em relação aos dois vizinhos da fronteira. As vantagens fiscais levaram multinacionais da Europa, dos EUA e da Ásia a colocarem nessas zonas francas seus pontos de escoamento para os demais países da região.

Essas empresas encontraram nesse país uma alternativa às rígidas restrições à importação na Argentina e aos gargalos portuários no Brasil, mesmo sendo o mercado brasileiro o principal cliente para a maioria.

Na Zonamérica só há empresas de serviços. O forte das atividades concentra-se nas áreas de logística, call centers, tecnologia da informação e serviços financeiros.

Entre a longa lista de vantagens oferecidas pelo país, estão elevado IDH, segurança, democracia, mão de obra bilíngue e qualificada, baixas posições em problemas como corrupção e liberdade no uso de moedas diferentes.

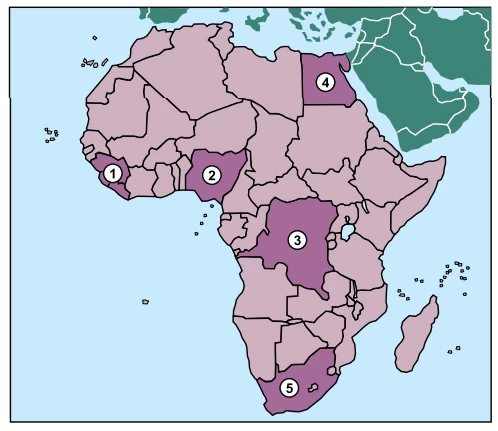

A África tem sido palco de inúmeros problemas sociais e - FGV 2015

Geografia - 2015A África tem sido palco de inúmeros problemas sociais e econômicos nos últimos anos. Observe o mapa a seguir:

Os impasses sobre a Ucrânia elevaram tensões entre a Rússia - FGV 2015

Geografia - 2015Os impasses sobre a Ucrânia elevaram tensões entre a Rússia e o Ocidente a níveis sem precedentes desde a Guerra Fria. As autoridades americanas e europeias alertaram para a possibilidade de a Rússia enfrentar sanções de amplo alcance em áreas como energia, finanças, manufaturas e agronegócios.

Sem a construção de novas hidrelétricas com grandes - FGV 2015

Geografia - 2015Sem a construção de novas hidrelétricas com grandes reservatórios, diminui a capacidade do Brasil de poupar água para produção de eletricidade nos meses de estiagem.

According to the first paragraph, (A) it took Argentina - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)

The explanation given by Argentina’s president, in the - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)

Argentina’s creditors, as the second paragraph shows, (A) - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)

In the excerpt from the end of the second paragraph – - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)

We learn in the article, mostly in paragraphs two through - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)

Argentina’s government argues that it can’t pay all - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)

The fourth paragraph points out that (A) as Argentina - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)

De acordo com a norma-padrão, se o verbo sublinhado no - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2015Texto para à questão

No mar de dúvidas

Há duas maneiras de aprender qualquer coisa: uma, leve, suave, com informações corretas mas superficiais, que, pela incompletude da lição, não indo aos assuntos a ela correlatos, acaba sendo insuficiente para permitir a fixação da aprendizagem. É um método que pode agradar, e até divertir o leitor menos exigente; mas não lhe garante o sucesso do conhecimento.

A segunda maneira é aquela que procura dar um passo à frente da resposta breve e imediata: estabelece relações entre a dúvida apresentada e outros assuntos afins, de modo que, aprofundando um pouco mais a lição, amplia o conhecimento e garante sua permanência, porque não se contenta em ficar na superfície dos problemas e das dúvidas.

Falamos em superfície, e a palavra nos sugere agora uma comparação entre as duas maneiras de aprender das quais vimos tratando. A primeira ensina a pessoa, no mar de dúvidas, a manter-se à superfície; não afunda, mas não sai do lugar. A segunda, além de permitir à pessoa permanecer à superfície, ensina-lhe a dar braçadas, ir mais além. Assim, pela primeira maneira, a pessoa boia; pela segunda, nadando, avança e chega a seu destino.

The excerpt from the fourth paragraph – had Argentina made - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)

In its fifth paragraph, the article (A) backs up Ms - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)

The word hers, as used in the second sentence of the fifth - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)

According to the sixth paragraph, (A) there is still room - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)

In the excerpt from the last paragraph – ... perceptions of - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)

The last paragraph implies that (A) returning Repsol to its - FGV 2015

Inglês - 2015Read the text and answer the question

Argentina defaults – Eighth time unlucky

Cristina Fernández argues that her country’s latest default is different. She is missing the point.

Aug 2nd 2014

ARGENTINA’S first bond, issued in 1824, was supposed to have had a lifespan of 46 years. Less than four years later, the government defaulted. Resolving the ensuing stand-off with creditors took 29 years. Since then seven more defaults have followed, the most recent this week, when Argentina failed to make a payment on bonds issued as partial compensation to victims of the previous default, in 2001.

Most investors think they can see a pattern in all this, but Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, insists the latest default is not like the others. Her government, she points out, had transferred the full $539m it owed to the banks that administer the bonds. It is America’s courts (the bonds were issued under American law) that blocked the payment, at the behest of the tiny minority of owners of bonds from 2001 who did not accept the restructuring Argentina offered them in 2005 and again in 2010. These “hold-outs”, balking at the 65% haircut the restructuring entailed, not only persuaded a judge that they should be paid in full but also got him to freeze payments on the restructured bonds until Argentina coughs up.

Argentina claims that paying the hold-outs was impossible. It is not just that they are “vultures” as Argentine officials often put it, who bought the bonds for cents on the dollar after the previous default and are now holding those who accepted the restructuring (accounting for 93% of the debt) to ransom. The main problem is that a clause in the restructured bonds prohibits Argentina from offering the hold-outs better terms without paying everyone else the same. Since it cannot afford to do that, it says it had no choice but to default.

Yet it is not certain that the clause requiring equal treatment of all bondholders would have applied, given that Argentina would not have been paying the hold-outs voluntarily, but on the courts’ orders. Moreover, some owners of the restructured bonds had agreed to waive their rights; had Argentina made a concerted effort to persuade the remainder to do the same, it might have succeeded. Lawyers and bankers have suggested various ways around the clause in question, which expires at the end of the year. But Argentina’s government was slow to consider these options or negotiate with the hold-outs, hiding instead behind indignant nationalism.

Ms Fernández is right that the consequences of America’s court rulings have been perverse, unleashing a big financial dispute in an attempt to solve a relatively small one. But hers is not the first government to be hit with an awkward verdict. Instead of railing against it, she should have tried to minimise the harm it did. Defaulting has helped no one: none of the bondholders will now be paid, Argentina looks like a pariah again, and its economy will remain starved of loans and investment.

Happily, much of the damage can still be undone. It is not too late to strike a deal with the hold-outs or back an ostensibly private effort to buy out their claims. A quick fix would make it easier for Argentina to borrow again internationally. That, in turn, would speed development of big oil and gas deposits, the income from which could help ease its money troubles.

More important, it would help to change perceptions of Argentina as a financial rogue state. Over the past year or so Ms Fernández seems to have been trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s image and resuscitate its faltering economy. She settled financial disputes with government creditors and with Repsol, a Spanish oil firm whose Argentine assets she had expropriated in 2012. This week’s events have overshadowed all that. For its own sake, and everyone else’s, Argentina should hold its nose and do a deal with the hold-outs.

(http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263. Adapted)