UNIFESP

Exibindo questões de 501 a 600.

O texto permite afirmar que a) o livro de orações que - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: A questão a seguir toma por base o texto.

Amaro lia até tarde, um pouco perturbado por aqueles períodos sonoros, túmidos de desejo; e no silêncio, por vezes, sentia em cima ranger o leito de Amélia; o livro escorregava-lhe das mãos, encostava a cabeça às costas da poltrona, cerrava os olhos, e parecia-lhe vê-la em colete diante do toucador desfazendo as tranças; ou, curvada, desapertando as ligas, e o decote da sua camisa entreaberta descobria os dois seios muito brancos.

Erguia-se, cerrando os dentes, com uma decisão brutal de a possuir.

Começara então a recomendar-lhe a leitura dos Cânticos a Jesus.

– Verá, é muito bonito, de muita devoção! Disse ele, deixando- lhe o livrinho uma noite no cesto da costura.

Ao outro dia, ao almoço, Amélia estava pálida, com as olheiras até o meio da face. Queixou-se de insônia, de palpitações.

– E então, gostou dos Cânticos?

– Muito. Orações lindas! respondeu.

Durante todo esse dia não ergueu os olhos para Amaro. Parecia triste – e sem razão, às vezes, o rosto abrasava-se-lhe de sangue.

(Eça de Queirós. O crime do padre Amaro.)

Indique a frase que, no contexto do fragmento - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: A questão por base o fragmento.

(...) Um poeta dizia que o menino é o pai do homem. Se isto é verdade, vejamos alguns lineamentos do menino.

Desde os cinco anos merecera eu a alcunha de “menino diabo”; e verdadeiramente não era outra coisa; fui dos mais malignos do meu tempo, arguto, indiscreto, traquinas e voluntarioso. Por exemplo, um dia quebrei a cabeça de uma escrava, porque me negara uma colher do doce de coco que estava fazendo, e, não contente com o malefício, deitei um punhado de cinza ao tacho, e, não satisfeito da travessura, fui dizer à minha mãe que a escrava é que estragara o doce “por pirraça”; e eu tinha apenas seis anos. Prudêncio, um moleque de casa, era o meu cavalo de todos os dias; punha as mãos no chão, recebia um cordel nos queixos, à guisa de freio, eu trepava-lhe ao dorso, com uma varinha na mão, fustiga - va-o, dava mil voltas a um e outro lado, e ele obedecia, – algumas vezes gemendo – mas obedecia sem dizer pala - vra, ou, quando muito, um – “ai, nhonhô!” – ao que eu retorquia: “Cala a boca, besta!” – Esconder os chapéus das visitas, deitar rabos de papel a pessoas graves, puxar pelo rabicho das cabeleiras, dar beliscões nos braços das matronas, e outras muitas façanhas deste jaez, eram mostras de um gênio indócil, mas devo crer que eram também expressões de um espírito robusto, porque meu pai tinha-me em grande admiração; e se às vezes me repreendia, à vista de gente, fazia-o por simples forma - lidade: em particular dava-me beijos.

Não se conclua daqui que eu levasse todo o resto da minha vida a quebrar a cabeça dos outros nem a esconder-lhes os chapéus; mas opiniático, egoísta e algo contemptor dos homens, isso fui; se não passei o tempo a esconder-lhes os chapéus, alguma vez lhes puxei pelo rabicho das cabeleiras.

(Machado de Assis. Memórias póstumas de Brás Cubas.)

É correto afirmar que a) se trata basicamente de um - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: A questão por base o fragmento.

(...) Um poeta dizia que o menino é o pai do homem. Se isto é verdade, vejamos alguns lineamentos do menino.

Desde os cinco anos merecera eu a alcunha de “menino diabo”; e verdadeiramente não era outra coisa; fui dos mais malignos do meu tempo, arguto, indiscreto, traquinas e voluntarioso. Por exemplo, um dia quebrei a cabeça de uma escrava, porque me negara uma colher do doce de coco que estava fazendo, e, não contente com o malefício, deitei um punhado de cinza ao tacho, e, não satisfeito da travessura, fui dizer à minha mãe que a escrava é que estragara o doce “por pirraça”; e eu tinha apenas seis anos. Prudêncio, um moleque de casa, era o meu cavalo de todos os dias; punha as mãos no chão, recebia um cordel nos queixos, à guisa de freio, eu trepava-lhe ao dorso, com uma varinha na mão, fustiga - va-o, dava mil voltas a um e outro lado, e ele obedecia, – algumas vezes gemendo – mas obedecia sem dizer pala - vra, ou, quando muito, um – “ai, nhonhô!” – ao que eu retorquia: “Cala a boca, besta!” – Esconder os chapéus das visitas, deitar rabos de papel a pessoas graves, puxar pelo rabicho das cabeleiras, dar beliscões nos braços das matronas, e outras muitas façanhas deste jaez, eram mostras de um gênio indócil, mas devo crer que eram também expressões de um espírito robusto, porque meu pai tinha-me em grande admiração; e se às vezes me repreendia, à vista de gente, fazia-o por simples forma - lidade: em particular dava-me beijos.

Não se conclua daqui que eu levasse todo o resto da minha vida a quebrar a cabeça dos outros nem a esconder-lhes os chapéus; mas opiniático, egoísta e algo contemptor dos homens, isso fui; se não passei o tempo a esconder-lhes os chapéus, alguma vez lhes puxei pelo rabicho das cabeleiras.

(Machado de Assis. Memórias póstumas de Brás Cubas.)

Para reforçar a caracterização do “menino diabo” - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: A questão por base o fragmento.

(...) Um poeta dizia que o menino é o pai do homem. Se isto é verdade, vejamos alguns lineamentos do menino.

Desde os cinco anos merecera eu a alcunha de “menino diabo”; e verdadeiramente não era outra coisa; fui dos mais malignos do meu tempo, arguto, indiscreto, traquinas e voluntarioso. Por exemplo, um dia quebrei a cabeça de uma escrava, porque me negara uma colher do doce de coco que estava fazendo, e, não contente com o malefício, deitei um punhado de cinza ao tacho, e, não satisfeito da travessura, fui dizer à minha mãe que a escrava é que estragara o doce “por pirraça”; e eu tinha apenas seis anos. Prudêncio, um moleque de casa, era o meu cavalo de todos os dias; punha as mãos no chão, recebia um cordel nos queixos, à guisa de freio, eu trepava-lhe ao dorso, com uma varinha na mão, fustiga - va-o, dava mil voltas a um e outro lado, e ele obedecia, – algumas vezes gemendo – mas obedecia sem dizer pala - vra, ou, quando muito, um – “ai, nhonhô!” – ao que eu retorquia: “Cala a boca, besta!” – Esconder os chapéus das visitas, deitar rabos de papel a pessoas graves, puxar pelo rabicho das cabeleiras, dar beliscões nos braços das matronas, e outras muitas façanhas deste jaez, eram mostras de um gênio indócil, mas devo crer que eram também expressões de um espírito robusto, porque meu pai tinha-me em grande admiração; e se às vezes me repreendia, à vista de gente, fazia-o por simples forma - lidade: em particular dava-me beijos.

Não se conclua daqui que eu levasse todo o resto da minha vida a quebrar a cabeça dos outros nem a esconder-lhes os chapéus; mas opiniático, egoísta e algo contemptor dos homens, isso fui; se não passei o tempo a esconder-lhes os chapéus, alguma vez lhes puxei pelo rabicho das cabeleiras.

(Machado de Assis. Memórias póstumas de Brás Cubas.)

A versão modificada, adaptada à oralidade – como - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

Crescia naturalmente

Fazendo estripulia,

Malino e muito arguto,

Gostava de zombaria.

A cabeça duma escrava

Quase arrebentei um dia.

E tudo isso porque

Um doce me havia negado,

De cinza no tacho cheio

Inda joguei um punhado,

Daí porque a alcunha

De “Menino Endiabrado”.

Prudêncio era um menino

Da casa, que agora falo.

Botava suas mãos no chão

Pra poder depois montá-lo:

Com um chicote na mão

Fazia dele um cavalo.

(Varneci Nascimento.

Memórias póstumas de Brás Cubas em cordel.)

Considere as seguintes afirmações: I. Os versos do - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

Crescia naturalmente

Fazendo estripulia,

Malino e muito arguto,

Gostava de zombaria.

A cabeça duma escrava

Quase arrebentei um dia.

E tudo isso porque

Um doce me havia negado,

De cinza no tacho cheio

Inda joguei um punhado,

Daí porque a alcunha

De “Menino Endiabrado”.

Prudêncio era um menino

Da casa, que agora falo.

Botava suas mãos no chão

Pra poder depois montá-lo:

Com um chicote na mão

Fazia dele um cavalo.

(Varneci Nascimento.

Memórias póstumas de Brás Cubas em cordel.)

Compare o trecho de Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Compare o trecho de Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas, de Machado de Assis, com o fragmento do poema O navio negreiro – tragédia no mar, de Castro Alves (questões 11 e 12).

Considere as seguintes afirmações. I. A alcunha de - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: A questão toma por base o fragmento seguinte.

As provocações no recreio eram frequentes, oriundas do enfado; irritadiços todos como feridas; os inspetores a cada passo precisavam intervir em conflitos; as importunações andavam em busca das suscetibilidades; as suscetibilidades a procurar a sarna das importunações. Viam de joelhos o Franco, puxavamlhe os cabelos. Viam Rômulo passar, lançavam-lhe o apelido: mestre-cuca!

Esta provocação era, além de tudo, inverdade. Cozinheiro, Rômulo! Só porque lembrava culinária, com a carnosidade bamba, fofada dos pastelões, ou porque era gordo das enxúndias enganadoras dos fregistas, dissolução mórbida de sardinha e azeite, sob os aspectos de mais volumosa saúde?

(...)

Rômulo era antipatizado. Para que o não manifestassem excessivamente, fazia-se temer pela brutalidade. Ao mais insignificante gracejo de um pequeno, atirava contra o infeliz toda a corpulência das infiltrações de gordura solta, desmoronava-se em socos. Dos mais fortes vingava-se, resmungando intrepidamente.

Para desesperá-lo, aproveitavam-se os menores do escuro. Rômulo, no meio, ficava tonto, esbravejando juras de morte, mostrando o punho. Em geral procurava reconhecer algum dos impertinentes e o marcava para a vindita. Vindita inexorável.

No decorrer enfadonho das últimas semanas, foi Rômulo escolhido, principalmente, para expiatório do desfastio. Mestrecuca! Via-se apregoado por vozes fantásticas, saídas da terra; mestre-cuca! Por vozes do espaço rouquenhas ou esganiçadas. Sentava-se acabrunhado, vendo se se lembrava de haver tratado panelas algum dia na vida; a unanimidade impressionava. Mais frequentemente, entregava-se a acessos de raiva. Arremetia bufando, espumando, olhos fechados, punhos para trás, contra os grupos. Os rapazes corriam a rir, abrindo caminho, deixando rolar adiante aquela ambulância danada de elefantíase.

(Raul Pompeia. O Ateneu.)

Indique a alternativa em que os fragmentos selecionados - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: A questão toma por base o fragmento seguinte.

As provocações no recreio eram frequentes, oriundas do enfado; irritadiços todos como feridas; os inspetores a cada passo precisavam intervir em conflitos; as importunações andavam em busca das suscetibilidades; as suscetibilidades a procurar a sarna das importunações. Viam de joelhos o Franco, puxavamlhe os cabelos. Viam Rômulo passar, lançavam-lhe o apelido: mestre-cuca!

Esta provocação era, além de tudo, inverdade. Cozinheiro, Rômulo! Só porque lembrava culinária, com a carnosidade bamba, fofada dos pastelões, ou porque era gordo das enxúndias enganadoras dos fregistas, dissolução mórbida de sardinha e azeite, sob os aspectos de mais volumosa saúde?

(...)

Rômulo era antipatizado. Para que o não manifestassem excessivamente, fazia-se temer pela brutalidade. Ao mais insignificante gracejo de um pequeno, atirava contra o infeliz toda a corpulência das infiltrações de gordura solta, desmoronava-se em socos. Dos mais fortes vingava-se, resmungando intrepidamente.

Para desesperá-lo, aproveitavam-se os menores do escuro. Rômulo, no meio, ficava tonto, esbravejando juras de morte, mostrando o punho. Em geral procurava reconhecer algum dos impertinentes e o marcava para a vindita. Vindita inexorável.

No decorrer enfadonho das últimas semanas, foi Rômulo escolhido, principalmente, para expiatório do desfastio. Mestrecuca! Via-se apregoado por vozes fantásticas, saídas da terra; mestre-cuca! Por vozes do espaço rouquenhas ou esganiçadas. Sentava-se acabrunhado, vendo se se lembrava de haver tratado panelas algum dia na vida; a unanimidade impressionava. Mais frequentemente, entregava-se a acessos de raiva. Arremetia bufando, espumando, olhos fechados, punhos para trás, contra os grupos. Os rapazes corriam a rir, abrindo caminho, deixando rolar adiante aquela ambulância danada de elefantíase.

(Raul Pompeia. O Ateneu.)

Sobre o texto, é correto afirmar: a) A atmosfera tensa - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: A questão toma por base o fragmento seguinte.

As provocações no recreio eram frequentes, oriundas do enfado; irritadiços todos como feridas; os inspetores a cada passo precisavam intervir em conflitos; as importunações andavam em busca das suscetibilidades; as suscetibilidades a procurar a sarna das importunações. Viam de joelhos o Franco, puxavamlhe os cabelos. Viam Rômulo passar, lançavam-lhe o apelido: mestre-cuca!

Esta provocação era, além de tudo, inverdade. Cozinheiro, Rômulo! Só porque lembrava culinária, com a carnosidade bamba, fofada dos pastelões, ou porque era gordo das enxúndias enganadoras dos fregistas, dissolução mórbida de sardinha e azeite, sob os aspectos de mais volumosa saúde?

(...)

Rômulo era antipatizado. Para que o não manifestassem excessivamente, fazia-se temer pela brutalidade. Ao mais insignificante gracejo de um pequeno, atirava contra o infeliz toda a corpulência das infiltrações de gordura solta, desmoronava-se em socos. Dos mais fortes vingava-se, resmungando intrepidamente.

Para desesperá-lo, aproveitavam-se os menores do escuro. Rômulo, no meio, ficava tonto, esbravejando juras de morte, mostrando o punho. Em geral procurava reconhecer algum dos impertinentes e o marcava para a vindita. Vindita inexorável.

No decorrer enfadonho das últimas semanas, foi Rômulo escolhido, principalmente, para expiatório do desfastio. Mestrecuca! Via-se apregoado por vozes fantásticas, saídas da terra; mestre-cuca! Por vozes do espaço rouquenhas ou esganiçadas. Sentava-se acabrunhado, vendo se se lembrava de haver tratado panelas algum dia na vida; a unanimidade impressionava. Mais frequentemente, entregava-se a acessos de raiva. Arremetia bufando, espumando, olhos fechados, punhos para trás, contra os grupos. Os rapazes corriam a rir, abrindo caminho, deixando rolar adiante aquela ambulância danada de elefantíase.

(Raul Pompeia. O Ateneu.)

Tendo em vista a função sintática da palavra grifada no - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: A questão toma por base o fragmento seguinte.

As provocações no recreio eram frequentes, oriundas do enfado; irritadiços todos como feridas; os inspetores a cada passo precisavam intervir em conflitos; as importunações andavam em busca das suscetibilidades; as suscetibilidades a procurar a sarna das importunações. Viam de joelhos o Franco, puxavamlhe os cabelos. Viam Rômulo passar, lançavam-lhe o apelido: mestre-cuca!

Esta provocação era, além de tudo, inverdade. Cozinheiro, Rômulo! Só porque lembrava culinária, com a carnosidade bamba, fofada dos pastelões, ou porque era gordo das enxúndias enganadoras dos fregistas, dissolução mórbida de sardinha e azeite, sob os aspectos de mais volumosa saúde?

(...)

Rômulo era antipatizado. Para que o não manifestassem excessivamente, fazia-se temer pela brutalidade. Ao mais insignificante gracejo de um pequeno, atirava contra o infeliz toda a corpulência das infiltrações de gordura solta, desmoronava-se em socos. Dos mais fortes vingava-se, resmungando intrepidamente.

Para desesperá-lo, aproveitavam-se os menores do escuro. Rômulo, no meio, ficava tonto, esbravejando juras de morte, mostrando o punho. Em geral procurava reconhecer algum dos impertinentes e o marcava para a vindita. Vindita inexorável.

No decorrer enfadonho das últimas semanas, foi Rômulo escolhido, principalmente, para expiatório do desfastio. Mestrecuca! Via-se apregoado por vozes fantásticas, saídas da terra; mestre-cuca! Por vozes do espaço rouquenhas ou esganiçadas. Sentava-se acabrunhado, vendo se se lembrava de haver tratado panelas algum dia na vida; a unanimidade impressionava. Mais frequentemente, entregava-se a acessos de raiva. Arremetia bufando, espumando, olhos fechados, punhos para trás, contra os grupos. Os rapazes corriam a rir, abrindo caminho, deixando rolar adiante aquela ambulância danada de elefantíase.

(Raul Pompeia. O Ateneu.)

Considere as afirmações seguintes. I. O fragmento do - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: A questão toma por base o fragmento.

[Sem-Pernas] queria alegria, uma mão que o acarinhasse, alguém que com muito amor o fizesse esquecer o defeito físico e os muitos anos (talvez tivessem sido apenas meses ou semanas, mas para ele seriam sempre longos anos) que vivera sozinho nas ruas da cidade, hostilizado pelos homens que passavam, empurrado pelos guardas, surrado pelos moleques maiores. Nunca tivera família. Vivera na casa de um padeiro a quem chamava “meu padrinho” e que o surrava. Fugiu logo que pôde compreender que a fuga o libertaria. Sofreu fome, um dia levaram-no preso. Ele quer um carinho, u’a mão que passe sobre os seus olhos e faça com que ele possa se esquecer daquela noite na cadeia, quando os soldados bêbados o fizeram correr com sua perna coxa em volta de uma saleta. Em cada canto estava um com uma borracha comprida. As marcas que ficaram nas suas costas desapareceram. Mas de dentro dele nunca desapareceu a dor daquela hora. Corria na saleta como um animal perseguido por outros mais fortes. A perna coxa se recusava a ajudá-lo. E a borracha zunia nas suas costas quando o cansaço o fazia parar. A princípio chorou muito, depois, não sabe como, as lágrimas secaram. Certa hora não resistiu mais, abateu-se no chão. Sangrava. Ainda hoje ouve como os soldados riam e como riu aquele homem de colete cinzento que fumava um charuto.

(Jorge Amado. Capitães da areia.)

O zigue-zague temporal ligado à vida de Sem-Pernas, - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: A questão toma por base o fragmento.

[Sem-Pernas] queria alegria, uma mão que o acarinhasse, alguém que com muito amor o fizesse esquecer o defeito físico e os muitos anos (talvez tivessem sido apenas meses ou semanas, mas para ele seriam sempre longos anos) que vivera sozinho nas ruas da cidade, hostilizado pelos homens que passavam, empurrado pelos guardas, surrado pelos moleques maiores. Nunca tivera família. Vivera na casa de um padeiro a quem chamava “meu padrinho” e que o surrava. Fugiu logo que pôde compreender que a fuga o libertaria. Sofreu fome, um dia levaram-no preso. Ele quer um carinho, u’a mão que passe sobre os seus olhos e faça com que ele possa se esquecer daquela noite na cadeia, quando os soldados bêbados o fizeram correr com sua perna coxa em volta de uma saleta. Em cada canto estava um com uma borracha comprida. As marcas que ficaram nas suas costas desapareceram. Mas de dentro dele nunca desapareceu a dor daquela hora. Corria na saleta como um animal perseguido por outros mais fortes. A perna coxa se recusava a ajudá-lo. E a borracha zunia nas suas costas quando o cansaço o fazia parar. A princípio chorou muito, depois, não sabe como, as lágrimas secaram. Certa hora não resistiu mais, abateu-se no chão. Sangrava. Ainda hoje ouve como os soldados riam e como riu aquele homem de colete cinzento que fumava um charuto.

(Jorge Amado. Capitães da areia.)

O emprego da figura de linguagem conhecida como - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011[Sem-Pernas] queria alegria, uma mão que o acarinhasse, alguém que com muito amor o fizesse esquecer o defeito físico e os muitos anos (talvez tivessem sido apenas meses ou semanas, mas para ele seriam sempre longos anos) que vivera sozinho nas ruas da cidade, hostilizado pelos homens que passavam, empurrado pelos guardas, surrado pelos moleques maiores. Nunca tivera família. Vivera na casa de um padeiro a quem chamava “meu padrinho” e que o surrava. Fugiu logo que pôde compreender que a fuga o libertaria. Sofreu fome, um dia levaram-no preso. Ele quer um carinho, u’a mão que passe sobre os seus olhos e faça com que ele possa se esquecer daquela noite na cadeia, quando os soldados bêbados o fizeram correr com sua perna coxa em volta de uma saleta. Em cada canto estava um com uma borracha comprida. As marcas que ficaram nas suas costas desapareceram. Mas de dentro dele nunca desapareceu a dor daquela hora. Corria na saleta como um animal perseguido por outros mais fortes. A perna coxa se recusava a ajudá-lo. E a borracha zunia nas suas costas quando o cansaço o fazia parar. A princípio chorou muito, depois, não sabe como, as lágrimas secaram. Certa hora não resistiu mais, abateu-se no chão. Sangrava. Ainda hoje ouve como os soldados riam e como riu aquele homem de colete cinzento que fumava um charuto.

(Jorge Amado. Capitães da areia.)

A partir do início do fragmento selecionado, uma série - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

De tudo que é nego torto

Do mangue e do cais do porto

Ela já foi namorada

O seu corpo é dos errantes

Dos cegos, dos retirantes

É de quem não tem mais nada

Dá-se assim desde menina

Na garagem, na cantina

Atrás do tanque, no mato

É a rainha dos detentos

Das loucas, dos lazarentos

Dos moleques do internato

E também vai amiúde

Co’os velhinhos sem saúde

E as viúvas sem porvir

Ela é um poço de bondade

E é por isso que a cidade

Vive sempre a repetir

Joga pedra na Geni

Joga pedra na Geni

Ela é feita pra apanhar

Ela é boa de cuspir

Ela dá pra qualquer um

Maldita Geni

(Chico Buarque. Geni e o zepelim.)

Indique a alternativa que identifica corretamente, de - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

De tudo que é nego torto

Do mangue e do cais do porto

Ela já foi namorada

O seu corpo é dos errantes

Dos cegos, dos retirantes

É de quem não tem mais nada

Dá-se assim desde menina

Na garagem, na cantina

Atrás do tanque, no mato

É a rainha dos detentos

Das loucas, dos lazarentos

Dos moleques do internato

E também vai amiúde

Co’os velhinhos sem saúde

E as viúvas sem porvir

Ela é um poço de bondade

E é por isso que a cidade

Vive sempre a repetir

Joga pedra na Geni

Joga pedra na Geni

Ela é feita pra apanhar

Ela é boa de cuspir

Ela dá pra qualquer um

Maldita Geni

(Chico Buarque. Geni e o zepelim.)

Indique a alternativa que apresenta a função sintática - UNIFESP 2011

Língua Portuguesa - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

De tudo que é nego torto

Do mangue e do cais do porto

Ela já foi namorada

O seu corpo é dos errantes

Dos cegos, dos retirantes

É de quem não tem mais nada

Dá-se assim desde menina

Na garagem, na cantina

Atrás do tanque, no mato

É a rainha dos detentos

Das loucas, dos lazarentos

Dos moleques do internato

E também vai amiúde

Co’os velhinhos sem saúde

E as viúvas sem porvir

Ela é um poço de bondade

E é por isso que a cidade

Vive sempre a repetir

Joga pedra na Geni

Joga pedra na Geni

Ela é feita pra apanhar

Ela é boa de cuspir

Ela dá pra qualquer um

Maldita Geni

(Chico Buarque. Geni e o zepelim.)

The dispute about the first plane to take off and fly - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

Brazil: the natural knowledge economy

Kirsten Bound – THE ATLAS OF IDEAS

If you grew up in Europe or North America you will no doubt have been taught in school that the Wright Brothers from Ohio invented and flew the first aeroplane – the Kitty Hawk – in 1903. But if you grew up in Brazil you will have been taught that the real inventor was in fact a Brazilian from Minas Gerais called Alberto Santos Dumont, whose 14-bis aeroplane took to the skies in 1906. This fierce historical debate, which turns on definitions of ‘practical airplanes’, the ability to launch unaided, length of time spent in the air and the credibility of witnesses, will not be resolved here. Yet it is a striking example of the lack of global recognition for Brazil’s achievements in innovation.

Almost a century later, in 2005, Santos Dumont’s intellectual heirs, the company Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica (EMBRAER), made aviation history of a different kind when they unveiled the Ipanema, the world’s first commercially produced aircraft to run solely on biofuels. This time, the world was watching. Scientific American credited it as one of the most important inventions of the year. The attention paid to the Ipanema reflects the growing interest in biofuels as a potential solution to climate change and rising energy demand. To their advocates, biofuels – most commonly bioethanol or biodiesel – offer a more secure, sustainable energy supply that can reduce carbon emissions by 50–60 per cent compared to fossil fuels.

From learning to fly to learning to cope with the environmental costs of flight, biofuel innovations like the Ipanema reflect some of the tensions of modern science, in which expanding the frontiers of human ingenuity goes hand in hand with managing the consequences. The recent backlash against biofuels, which has seen them blamed for global food shortages as land is reportedly diverted from food crops, points to a growing interdependence between the science and innovation systems of different countries, and between innovation, economics and environmental sustainability.

The debates now raging over biofuels reflect some of the wider dynamics in Brazil’s innovation system. They remind us that Brazil’s current strengths and achievements have deeper historical roots than is sometimes imagined. They reflect the fact that Brazil’s natural resources and assets are a key area of opportunity for science and innovation – a focus that leads us to characterise Brazil as a ‘natural knowledge economy’. Most importantly, they highlight the propitious timing of Brazil’s growing strength in these areas at a time when climate change, the environment, food scarcity and rising worldwide energy demand are at the forefront of global consciousness. What changed between the maiden flight of the 14-bis and the maiden flight of the Ipanema is not just Brazil’s capacity for technological and scientific innovation, but the rest of the world’s appreciation of the potential of that innovation to address some of the pressing challenges that confront us all.

(www.demos.co.uk. Adaptado.)

According to the text, in Brazil people learn that a) - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

Brazil: the natural knowledge economy

Kirsten Bound – THE ATLAS OF IDEAS

If you grew up in Europe or North America you will no doubt have been taught in school that the Wright Brothers from Ohio invented and flew the first aeroplane – the Kitty Hawk – in 1903. But if you grew up in Brazil you will have been taught that the real inventor was in fact a Brazilian from Minas Gerais called Alberto Santos Dumont, whose 14-bis aeroplane took to the skies in 1906. This fierce historical debate, which turns on definitions of ‘practical airplanes’, the ability to launch unaided, length of time spent in the air and the credibility of witnesses, will not be resolved here. Yet it is a striking example of the lack of global recognition for Brazil’s achievements in innovation.

Almost a century later, in 2005, Santos Dumont’s intellectual heirs, the company Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica (EMBRAER), made aviation history of a different kind when they unveiled the Ipanema, the world’s first commercially produced aircraft to run solely on biofuels. This time, the world was watching. Scientific American credited it as one of the most important inventions of the year. The attention paid to the Ipanema reflects the growing interest in biofuels as a potential solution to climate change and rising energy demand. To their advocates, biofuels – most commonly bioethanol or biodiesel – offer a more secure, sustainable energy supply that can reduce carbon emissions by 50–60 per cent compared to fossil fuels.

From learning to fly to learning to cope with the environmental costs of flight, biofuel innovations like the Ipanema reflect some of the tensions of modern science, in which expanding the frontiers of human ingenuity goes hand in hand with managing the consequences. The recent backlash against biofuels, which has seen them blamed for global food shortages as land is reportedly diverted from food crops, points to a growing interdependence between the science and innovation systems of different countries, and between innovation, economics and environmental sustainability.

The debates now raging over biofuels reflect some of the wider dynamics in Brazil’s innovation system. They remind us that Brazil’s current strengths and achievements have deeper historical roots than is sometimes imagined. They reflect the fact that Brazil’s natural resources and assets are a key area of opportunity for science and innovation – a focus that leads us to characterise Brazil as a ‘natural knowledge economy’. Most importantly, they highlight the propitious timing of Brazil’s growing strength in these areas at a time when climate change, the environment, food scarcity and rising worldwide energy demand are at the forefront of global consciousness. What changed between the maiden flight of the 14-bis and the maiden flight of the Ipanema is not just Brazil’s capacity for technological and scientific innovation, but the rest of the world’s appreciation of the potential of that innovation to address some of the pressing challenges that confront us all.

(www.demos.co.uk. Adaptado.)

Segundo o texto, a aeronave Ipanema a) demonstrou que - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

Brazil: the natural knowledge economy

Kirsten Bound – THE ATLAS OF IDEAS

If you grew up in Europe or North America you will no doubt have been taught in school that the Wright Brothers from Ohio invented and flew the first aeroplane – the Kitty Hawk – in 1903. But if you grew up in Brazil you will have been taught that the real inventor was in fact a Brazilian from Minas Gerais called Alberto Santos Dumont, whose 14-bis aeroplane took to the skies in 1906. This fierce historical debate, which turns on definitions of ‘practical airplanes’, the ability to launch unaided, length of time spent in the air and the credibility of witnesses, will not be resolved here. Yet it is a striking example of the lack of global recognition for Brazil’s achievements in innovation.

Almost a century later, in 2005, Santos Dumont’s intellectual heirs, the company Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica (EMBRAER), made aviation history of a different kind when they unveiled the Ipanema, the world’s first commercially produced aircraft to run solely on biofuels. This time, the world was watching. Scientific American credited it as one of the most important inventions of the year. The attention paid to the Ipanema reflects the growing interest in biofuels as a potential solution to climate change and rising energy demand. To their advocates, biofuels – most commonly bioethanol or biodiesel – offer a more secure, sustainable energy supply that can reduce carbon emissions by 50–60 per cent compared to fossil fuels.

From learning to fly to learning to cope with the environmental costs of flight, biofuel innovations like the Ipanema reflect some of the tensions of modern science, in which expanding the frontiers of human ingenuity goes hand in hand with managing the consequences. The recent backlash against biofuels, which has seen them blamed for global food shortages as land is reportedly diverted from food crops, points to a growing interdependence between the science and innovation systems of different countries, and between innovation, economics and environmental sustainability.

The debates now raging over biofuels reflect some of the wider dynamics in Brazil’s innovation system. They remind us that Brazil’s current strengths and achievements have deeper historical roots than is sometimes imagined. They reflect the fact that Brazil’s natural resources and assets are a key area of opportunity for science and innovation – a focus that leads us to characterise Brazil as a ‘natural knowledge economy’. Most importantly, they highlight the propitious timing of Brazil’s growing strength in these areas at a time when climate change, the environment, food scarcity and rising worldwide energy demand are at the forefront of global consciousness. What changed between the maiden flight of the 14-bis and the maiden flight of the Ipanema is not just Brazil’s capacity for technological and scientific innovation, but the rest of the world’s appreciation of the potential of that innovation to address some of the pressing challenges that confront us all.

(www.demos.co.uk. Adaptado.)

According to the text, biofuels a) have caused a strong - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

Brazil: the natural knowledge economy

Kirsten Bound – THE ATLAS OF IDEAS

If you grew up in Europe or North America you will no doubt have been taught in school that the Wright Brothers from Ohio invented and flew the first aeroplane – the Kitty Hawk – in 1903. But if you grew up in Brazil you will have been taught that the real inventor was in fact a Brazilian from Minas Gerais called Alberto Santos Dumont, whose 14-bis aeroplane took to the skies in 1906. This fierce historical debate, which turns on definitions of ‘practical airplanes’, the ability to launch unaided, length of time spent in the air and the credibility of witnesses, will not be resolved here. Yet it is a striking example of the lack of global recognition for Brazil’s achievements in innovation.

Almost a century later, in 2005, Santos Dumont’s intellectual heirs, the company Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica (EMBRAER), made aviation history of a different kind when they unveiled the Ipanema, the world’s first commercially produced aircraft to run solely on biofuels. This time, the world was watching. Scientific American credited it as one of the most important inventions of the year. The attention paid to the Ipanema reflects the growing interest in biofuels as a potential solution to climate change and rising energy demand. To their advocates, biofuels – most commonly bioethanol or biodiesel – offer a more secure, sustainable energy supply that can reduce carbon emissions by 50–60 per cent compared to fossil fuels.

From learning to fly to learning to cope with the environmental costs of flight, biofuel innovations like the Ipanema reflect some of the tensions of modern science, in which expanding the frontiers of human ingenuity goes hand in hand with managing the consequences. The recent backlash against biofuels, which has seen them blamed for global food shortages as land is reportedly diverted from food crops, points to a growing interdependence between the science and innovation systems of different countries, and between innovation, economics and environmental sustainability.

The debates now raging over biofuels reflect some of the wider dynamics in Brazil’s innovation system. They remind us that Brazil’s current strengths and achievements have deeper historical roots than is sometimes imagined. They reflect the fact that Brazil’s natural resources and assets are a key area of opportunity for science and innovation – a focus that leads us to characterise Brazil as a ‘natural knowledge economy’. Most importantly, they highlight the propitious timing of Brazil’s growing strength in these areas at a time when climate change, the environment, food scarcity and rising worldwide energy demand are at the forefront of global consciousness. What changed between the maiden flight of the 14-bis and the maiden flight of the Ipanema is not just Brazil’s capacity for technological and scientific innovation, but the rest of the world’s appreciation of the potential of that innovation to address some of the pressing challenges that confront us all.

(www.demos.co.uk. Adaptado.)

Brazil is characterized as a ‘natural knowledge economy - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

Brazil: the natural knowledge economy

Kirsten Bound – THE ATLAS OF IDEAS

If you grew up in Europe or North America you will no doubt have been taught in school that the Wright Brothers from Ohio invented and flew the first aeroplane – the Kitty Hawk – in 1903. But if you grew up in Brazil you will have been taught that the real inventor was in fact a Brazilian from Minas Gerais called Alberto Santos Dumont, whose 14-bis aeroplane took to the skies in 1906. This fierce historical debate, which turns on definitions of ‘practical airplanes’, the ability to launch unaided, length of time spent in the air and the credibility of witnesses, will not be resolved here. Yet it is a striking example of the lack of global recognition for Brazil’s achievements in innovation.

Almost a century later, in 2005, Santos Dumont’s intellectual heirs, the company Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica (EMBRAER), made aviation history of a different kind when they unveiled the Ipanema, the world’s first commercially produced aircraft to run solely on biofuels. This time, the world was watching. Scientific American credited it as one of the most important inventions of the year. The attention paid to the Ipanema reflects the growing interest in biofuels as a potential solution to climate change and rising energy demand. To their advocates, biofuels – most commonly bioethanol or biodiesel – offer a more secure, sustainable energy supply that can reduce carbon emissions by 50–60 per cent compared to fossil fuels.

From learning to fly to learning to cope with the environmental costs of flight, biofuel innovations like the Ipanema reflect some of the tensions of modern science, in which expanding the frontiers of human ingenuity goes hand in hand with managing the consequences. The recent backlash against biofuels, which has seen them blamed for global food shortages as land is reportedly diverted from food crops, points to a growing interdependence between the science and innovation systems of different countries, and between innovation, economics and environmental sustainability.

The debates now raging over biofuels reflect some of the wider dynamics in Brazil’s innovation system. They remind us that Brazil’s current strengths and achievements have deeper historical roots than is sometimes imagined. They reflect the fact that Brazil’s natural resources and assets are a key area of opportunity for science and innovation – a focus that leads us to characterise Brazil as a ‘natural knowledge economy’. Most importantly, they highlight the propitious timing of Brazil’s growing strength in these areas at a time when climate change, the environment, food scarcity and rising worldwide energy demand are at the forefront of global consciousness. What changed between the maiden flight of the 14-bis and the maiden flight of the Ipanema is not just Brazil’s capacity for technological and scientific innovation, but the rest of the world’s appreciation of the potential of that innovation to address some of the pressing challenges that confront us all.

(www.demos.co.uk. Adaptado.)

O trecho do segundo parágrafo – This time, the world - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

Brazil: the natural knowledge economy

Kirsten Bound – THE ATLAS OF IDEAS

If you grew up in Europe or North America you will no doubt have been taught in school that the Wright Brothers from Ohio invented and flew the first aeroplane – the Kitty Hawk – in 1903. But if you grew up in Brazil you will have been taught that the real inventor was in fact a Brazilian from Minas Gerais called Alberto Santos Dumont, whose 14-bis aeroplane took to the skies in 1906. This fierce historical debate, which turns on definitions of ‘practical airplanes’, the ability to launch unaided, length of time spent in the air and the credibility of witnesses, will not be resolved here. Yet it is a striking example of the lack of global recognition for Brazil’s achievements in innovation.

Almost a century later, in 2005, Santos Dumont’s intellectual heirs, the company Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica (EMBRAER), made aviation history of a different kind when they unveiled the Ipanema, the world’s first commercially produced aircraft to run solely on biofuels. This time, the world was watching. Scientific American credited it as one of the most important inventions of the year. The attention paid to the Ipanema reflects the growing interest in biofuels as a potential solution to climate change and rising energy demand. To their advocates, biofuels – most commonly bioethanol or biodiesel – offer a more secure, sustainable energy supply that can reduce carbon emissions by 50–60 per cent compared to fossil fuels.

From learning to fly to learning to cope with the environmental costs of flight, biofuel innovations like the Ipanema reflect some of the tensions of modern science, in which expanding the frontiers of human ingenuity goes hand in hand with managing the consequences. The recent backlash against biofuels, which has seen them blamed for global food shortages as land is reportedly diverted from food crops, points to a growing interdependence between the science and innovation systems of different countries, and between innovation, economics and environmental sustainability.

The debates now raging over biofuels reflect some of the wider dynamics in Brazil’s innovation system. They remind us that Brazil’s current strengths and achievements have deeper historical roots than is sometimes imagined. They reflect the fact that Brazil’s natural resources and assets are a key area of opportunity for science and innovation – a focus that leads us to characterise Brazil as a ‘natural knowledge economy’. Most importantly, they highlight the propitious timing of Brazil’s growing strength in these areas at a time when climate change, the environment, food scarcity and rising worldwide energy demand are at the forefront of global consciousness. What changed between the maiden flight of the 14-bis and the maiden flight of the Ipanema is not just Brazil’s capacity for technological and scientific innovation, but the rest of the world’s appreciation of the potential of that innovation to address some of the pressing challenges that confront us all.

(www.demos.co.uk. Adaptado.)

No trecho do segundo parágrafo – To their advocates - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

Brazil: the natural knowledge economy

Kirsten Bound – THE ATLAS OF IDEAS

If you grew up in Europe or North America you will no doubt have been taught in school that the Wright Brothers from Ohio invented and flew the first aeroplane – the Kitty Hawk – in 1903. But if you grew up in Brazil you will have been taught that the real inventor was in fact a Brazilian from Minas Gerais called Alberto Santos Dumont, whose 14-bis aeroplane took to the skies in 1906. This fierce historical debate, which turns on definitions of ‘practical airplanes’, the ability to launch unaided, length of time spent in the air and the credibility of witnesses, will not be resolved here. Yet it is a striking example of the lack of global recognition for Brazil’s achievements in innovation.

Almost a century later, in 2005, Santos Dumont’s intellectual heirs, the company Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica (EMBRAER), made aviation history of a different kind when they unveiled the Ipanema, the world’s first commercially produced aircraft to run solely on biofuels. This time, the world was watching. Scientific American credited it as one of the most important inventions of the year. The attention paid to the Ipanema reflects the growing interest in biofuels as a potential solution to climate change and rising energy demand. To their advocates, biofuels – most commonly bioethanol or biodiesel – offer a more secure, sustainable energy supply that can reduce carbon emissions by 50–60 per cent compared to fossil fuels.

From learning to fly to learning to cope with the environmental costs of flight, biofuel innovations like the Ipanema reflect some of the tensions of modern science, in which expanding the frontiers of human ingenuity goes hand in hand with managing the consequences. The recent backlash against biofuels, which has seen them blamed for global food shortages as land is reportedly diverted from food crops, points to a growing interdependence between the science and innovation systems of different countries, and between innovation, economics and environmental sustainability.

The debates now raging over biofuels reflect some of the wider dynamics in Brazil’s innovation system. They remind us that Brazil’s current strengths and achievements have deeper historical roots than is sometimes imagined. They reflect the fact that Brazil’s natural resources and assets are a key area of opportunity for science and innovation – a focus that leads us to characterise Brazil as a ‘natural knowledge economy’. Most importantly, they highlight the propitious timing of Brazil’s growing strength in these areas at a time when climate change, the environment, food scarcity and rising worldwide energy demand are at the forefront of global consciousness. What changed between the maiden flight of the 14-bis and the maiden flight of the Ipanema is not just Brazil’s capacity for technological and scientific innovation, but the rest of the world’s appreciation of the potential of that innovation to address some of the pressing challenges that confront us all.

(www.demos.co.uk. Adaptado.)

No trecho do terceiro parágrafo – which has seen them - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

Brazil: the natural knowledge economy

Kirsten Bound – THE ATLAS OF IDEAS

If you grew up in Europe or North America you will no doubt have been taught in school that the Wright Brothers from Ohio invented and flew the first aeroplane – the Kitty Hawk – in 1903. But if you grew up in Brazil you will have been taught that the real inventor was in fact a Brazilian from Minas Gerais called Alberto Santos Dumont, whose 14-bis aeroplane took to the skies in 1906. This fierce historical debate, which turns on definitions of ‘practical airplanes’, the ability to launch unaided, length of time spent in the air and the credibility of witnesses, will not be resolved here. Yet it is a striking example of the lack of global recognition for Brazil’s achievements in innovation.

Almost a century later, in 2005, Santos Dumont’s intellectual heirs, the company Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica (EMBRAER), made aviation history of a different kind when they unveiled the Ipanema, the world’s first commercially produced aircraft to run solely on biofuels. This time, the world was watching. Scientific American credited it as one of the most important inventions of the year. The attention paid to the Ipanema reflects the growing interest in biofuels as a potential solution to climate change and rising energy demand. To their advocates, biofuels – most commonly bioethanol or biodiesel – offer a more secure, sustainable energy supply that can reduce carbon emissions by 50–60 per cent compared to fossil fuels.

From learning to fly to learning to cope with the environmental costs of flight, biofuel innovations like the Ipanema reflect some of the tensions of modern science, in which expanding the frontiers of human ingenuity goes hand in hand with managing the consequences. The recent backlash against biofuels, which has seen them blamed for global food shortages as land is reportedly diverted from food crops, points to a growing interdependence between the science and innovation systems of different countries, and between innovation, economics and environmental sustainability.

The debates now raging over biofuels reflect some of the wider dynamics in Brazil’s innovation system. They remind us that Brazil’s current strengths and achievements have deeper historical roots than is sometimes imagined. They reflect the fact that Brazil’s natural resources and assets are a key area of opportunity for science and innovation – a focus that leads us to characterise Brazil as a ‘natural knowledge economy’. Most importantly, they highlight the propitious timing of Brazil’s growing strength in these areas at a time when climate change, the environment, food scarcity and rising worldwide energy demand are at the forefront of global consciousness. What changed between the maiden flight of the 14-bis and the maiden flight of the Ipanema is not just Brazil’s capacity for technological and scientific innovation, but the rest of the world’s appreciation of the potential of that innovation to address some of the pressing challenges that confront us all.

(www.demos.co.uk. Adaptado.)

An example of the pressing challenges mentioned in - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011Instrução: Leia o texto para responder a questão.

Brazil: the natural knowledge economy

Kirsten Bound – THE ATLAS OF IDEAS

If you grew up in Europe or North America you will no doubt have been taught in school that the Wright Brothers from Ohio invented and flew the first aeroplane – the Kitty Hawk – in 1903. But if you grew up in Brazil you will have been taught that the real inventor was in fact a Brazilian from Minas Gerais called Alberto Santos Dumont, whose 14-bis aeroplane took to the skies in 1906. This fierce historical debate, which turns on definitions of ‘practical airplanes’, the ability to launch unaided, length of time spent in the air and the credibility of witnesses, will not be resolved here. Yet it is a striking example of the lack of global recognition for Brazil’s achievements in innovation.

Almost a century later, in 2005, Santos Dumont’s intellectual heirs, the company Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica (EMBRAER), made aviation history of a different kind when they unveiled the Ipanema, the world’s first commercially produced aircraft to run solely on biofuels. This time, the world was watching. Scientific American credited it as one of the most important inventions of the year. The attention paid to the Ipanema reflects the growing interest in biofuels as a potential solution to climate change and rising energy demand. To their advocates, biofuels – most commonly bioethanol or biodiesel – offer a more secure, sustainable energy supply that can reduce carbon emissions by 50–60 per cent compared to fossil fuels.

From learning to fly to learning to cope with the environmental costs of flight, biofuel innovations like the Ipanema reflect some of the tensions of modern science, in which expanding the frontiers of human ingenuity goes hand in hand with managing the consequences. The recent backlash against biofuels, which has seen them blamed for global food shortages as land is reportedly diverted from food crops, points to a growing interdependence between the science and innovation systems of different countries, and between innovation, economics and environmental sustainability.

The debates now raging over biofuels reflect some of the wider dynamics in Brazil’s innovation system. They remind us that Brazil’s current strengths and achievements have deeper historical roots than is sometimes imagined. They reflect the fact that Brazil’s natural resources and assets are a key area of opportunity for science and innovation – a focus that leads us to characterise Brazil as a ‘natural knowledge economy’. Most importantly, they highlight the propitious timing of Brazil’s growing strength in these areas at a time when climate change, the environment, food scarcity and rising worldwide energy demand are at the forefront of global consciousness. What changed between the maiden flight of the 14-bis and the maiden flight of the Ipanema is not just Brazil’s capacity for technological and scientific innovation, but the rest of the world’s appreciation of the potential of that innovation to address some of the pressing challenges that confront us all.

(www.demos.co.uk. Adaptado.)

Segundo o texto, a risada a) foi estudada pelos cientis - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011To Scientists, Laughter Is No Joke - It’s Serious

March 31, 2010. So a scientist walks into a shopping mall to watch people laugh. There’s no punchline. Laughter is a serious scientific subject, one that researchers are still trying to figure out. Laughing is primal, our first way of communicating. Apes laugh. So do dogs and rats. Babies laugh long before they speak. No one teaches you how to laugh. You just do. And often you laugh involuntarily, in a specific rhythm and in certain spots in conversation.

You may laugh at a prank on April Fools’ Day. But surprisingly, only 10 to 15 percent of laughter is the result of someone making a joke, said Baltimore neuroscientist Robert Provine, who has studied laughter for decades. Laughter is mostly about social responses rather than reaction to a joke. “Laughter above all else is a social thing,’’ Provine said. “The requirement for laughter is another person.’’

Over the years, Provine, a professor with the University of Maryland Baltimore County, has boiled laughter down to its basics. “All language groups laugh ‘ha-ha-ha’ basically the same way,’’ he said. “Whether you speak Mandarin, French or English, everyone will understand laughter. ... There’s a pattern generator in our brain that produces this sound.’’

Each “ha’’ is about one-15th of a second, repeated every fifth of a second, he said. Laugh faster or slower than that and it sounds more like panting or something else. Deaf people laugh without hearing, and people on cell phones laugh without seeing, illustrating that laughter isn’t dependent on a single sense but on social interactions, said Provine, author of the book “Laughter: A Scientific Investigation.’’

“It’s joy, it’s positive engagement with life,’’ said Jaak Panksepp, a Bowling Green University psychology professor. “It’s deeply social.’’ And it’s not just a people thing either. Chimps tickle each other and even laugh when another chimp pretends to tickle them. By studying rats, Panksepp and other scientists can figure out what’s going on in the brain during laughter. And it holds promise for human ills.

Northwestern biomedical engineering professor Jeffrey Burgdorf has found that laughter in rats produces an insulin-like growth factor chemical that acts as an antidepressant and anxietyreducer. He thinks the same thing probably happens in humans, too. This would give doctors a new chemical target in the brain in their effort to develop drugs that fight depression and anxiety in people. Even so, laughter itself hasn’t been proven to be the best medicine, experts said.

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

According to the text, a) chimpanzees have the same - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011To Scientists, Laughter Is No Joke - It’s Serious

March 31, 2010. So a scientist walks into a shopping mall to watch people laugh. There’s no punchline. Laughter is a serious scientific subject, one that researchers are still trying to figure out. Laughing is primal, our first way of communicating. Apes laugh. So do dogs and rats. Babies laugh long before they speak. No one teaches you how to laugh. You just do. And often you laugh involuntarily, in a specific rhythm and in certain spots in conversation.

You may laugh at a prank on April Fools’ Day. But surprisingly, only 10 to 15 percent of laughter is the result of someone making a joke, said Baltimore neuroscientist Robert Provine, who has studied laughter for decades. Laughter is mostly about social responses rather than reaction to a joke. “Laughter above all else is a social thing,’’ Provine said. “The requirement for laughter is another person.’’

Over the years, Provine, a professor with the University of Maryland Baltimore County, has boiled laughter down to its basics. “All language groups laugh ‘ha-ha-ha’ basically the same way,’’ he said. “Whether you speak Mandarin, French or English, everyone will understand laughter. ... There’s a pattern generator in our brain that produces this sound.’’

Each “ha’’ is about one-15th of a second, repeated every fifth of a second, he said. Laugh faster or slower than that and it sounds more like panting or something else. Deaf people laugh without hearing, and people on cell phones laugh without seeing, illustrating that laughter isn’t dependent on a single sense but on social interactions, said Provine, author of the book “Laughter: A Scientific Investigation.’’

“It’s joy, it’s positive engagement with life,’’ said Jaak Panksepp, a Bowling Green University psychology professor. “It’s deeply social.’’ And it’s not just a people thing either. Chimps tickle each other and even laugh when another chimp pretends to tickle them. By studying rats, Panksepp and other scientists can figure out what’s going on in the brain during laughter. And it holds promise for human ills.

Northwestern biomedical engineering professor Jeffrey Burgdorf has found that laughter in rats produces an insulin-like growth factor chemical that acts as an antidepressant and anxietyreducer. He thinks the same thing probably happens in humans, too. This would give doctors a new chemical target in the brain in their effort to develop drugs that fight depression and anxiety in people. Even so, laughter itself hasn’t been proven to be the best medicine, experts said.

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Jeffrey Burgdorf discovered that a) rats that laugh - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011To Scientists, Laughter Is No Joke - It’s Serious

March 31, 2010. So a scientist walks into a shopping mall to watch people laugh. There’s no punchline. Laughter is a serious scientific subject, one that researchers are still trying to figure out. Laughing is primal, our first way of communicating. Apes laugh. So do dogs and rats. Babies laugh long before they speak. No one teaches you how to laugh. You just do. And often you laugh involuntarily, in a specific rhythm and in certain spots in conversation.

You may laugh at a prank on April Fools’ Day. But surprisingly, only 10 to 15 percent of laughter is the result of someone making a joke, said Baltimore neuroscientist Robert Provine, who has studied laughter for decades. Laughter is mostly about social responses rather than reaction to a joke. “Laughter above all else is a social thing,’’ Provine said. “The requirement for laughter is another person.’’

Over the years, Provine, a professor with the University of Maryland Baltimore County, has boiled laughter down to its basics. “All language groups laugh ‘ha-ha-ha’ basically the same way,’’ he said. “Whether you speak Mandarin, French or English, everyone will understand laughter. ... There’s a pattern generator in our brain that produces this sound.’’

Each “ha’’ is about one-15th of a second, repeated every fifth of a second, he said. Laugh faster or slower than that and it sounds more like panting or something else. Deaf people laugh without hearing, and people on cell phones laugh without seeing, illustrating that laughter isn’t dependent on a single sense but on social interactions, said Provine, author of the book “Laughter: A Scientific Investigation.’’

“It’s joy, it’s positive engagement with life,’’ said Jaak Panksepp, a Bowling Green University psychology professor. “It’s deeply social.’’ And it’s not just a people thing either. Chimps tickle each other and even laugh when another chimp pretends to tickle them. By studying rats, Panksepp and other scientists can figure out what’s going on in the brain during laughter. And it holds promise for human ills.

Northwestern biomedical engineering professor Jeffrey Burgdorf has found that laughter in rats produces an insulin-like growth factor chemical that acts as an antidepressant and anxietyreducer. He thinks the same thing probably happens in humans, too. This would give doctors a new chemical target in the brain in their effort to develop drugs that fight depression and anxiety in people. Even so, laughter itself hasn’t been proven to be the best medicine, experts said.

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

The excerpt of the first paragraph – You just do. - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011To Scientists, Laughter Is No Joke - It’s Serious

March 31, 2010. So a scientist walks into a shopping mall to watch people laugh. There’s no punchline. Laughter is a serious scientific subject, one that researchers are still trying to figure out. Laughing is primal, our first way of communicating. Apes laugh. So do dogs and rats. Babies laugh long before they speak. No one teaches you how to laugh. You just do. And often you laugh involuntarily, in a specific rhythm and in certain spots in conversation.

You may laugh at a prank on April Fools’ Day. But surprisingly, only 10 to 15 percent of laughter is the result of someone making a joke, said Baltimore neuroscientist Robert Provine, who has studied laughter for decades. Laughter is mostly about social responses rather than reaction to a joke. “Laughter above all else is a social thing,’’ Provine said. “The requirement for laughter is another person.’’

Over the years, Provine, a professor with the University of Maryland Baltimore County, has boiled laughter down to its basics. “All language groups laugh ‘ha-ha-ha’ basically the same way,’’ he said. “Whether you speak Mandarin, French or English, everyone will understand laughter. ... There’s a pattern generator in our brain that produces this sound.’’

Each “ha’’ is about one-15th of a second, repeated every fifth of a second, he said. Laugh faster or slower than that and it sounds more like panting or something else. Deaf people laugh without hearing, and people on cell phones laugh without seeing, illustrating that laughter isn’t dependent on a single sense but on social interactions, said Provine, author of the book “Laughter: A Scientific Investigation.’’

“It’s joy, it’s positive engagement with life,’’ said Jaak Panksepp, a Bowling Green University psychology professor. “It’s deeply social.’’ And it’s not just a people thing either. Chimps tickle each other and even laugh when another chimp pretends to tickle them. By studying rats, Panksepp and other scientists can figure out what’s going on in the brain during laughter. And it holds promise for human ills.

Northwestern biomedical engineering professor Jeffrey Burgdorf has found that laughter in rats produces an insulin-like growth factor chemical that acts as an antidepressant and anxietyreducer. He thinks the same thing probably happens in humans, too. This would give doctors a new chemical target in the brain in their effort to develop drugs that fight depression and anxiety in people. Even so, laughter itself hasn’t been proven to be the best medicine, experts said.

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

No trecho do quarto parágrafo – Laugh faster or slower - UNIFESP 2011

Inglês - 2011To Scientists, Laughter Is No Joke - It’s Serious

March 31, 2010. So a scientist walks into a shopping mall to watch people laugh. There’s no punchline. Laughter is a serious scientific subject, one that researchers are still trying to figure out. Laughing is primal, our first way of communicating. Apes laugh. So do dogs and rats. Babies laugh long before they speak. No one teaches you how to laugh. You just do. And often you laugh involuntarily, in a specific rhythm and in certain spots in conversation.

You may laugh at a prank on April Fools’ Day. But surprisingly, only 10 to 15 percent of laughter is the result of someone making a joke, said Baltimore neuroscientist Robert Provine, who has studied laughter for decades. Laughter is mostly about social responses rather than reaction to a joke. “Laughter above all else is a social thing,’’ Provine said. “The requirement for laughter is another person.’’

Over the years, Provine, a professor with the University of Maryland Baltimore County, has boiled laughter down to its basics. “All language groups laugh ‘ha-ha-ha’ basically the same way,’’ he said. “Whether you speak Mandarin, French or English, everyone will understand laughter. ... There’s a pattern generator in our brain that produces this sound.’’

Each “ha’’ is about one-15th of a second, repeated every fifth of a second, he said. Laugh faster or slower than that and it sounds more like panting or something else. Deaf people laugh without hearing, and people on cell phones laugh without seeing, illustrating that laughter isn’t dependent on a single sense but on social interactions, said Provine, author of the book “Laughter: A Scientific Investigation.’’

“It’s joy, it’s positive engagement with life,’’ said Jaak Panksepp, a Bowling Green University psychology professor. “It’s deeply social.’’ And it’s not just a people thing either. Chimps tickle each other and even laugh when another chimp pretends to tickle them. By studying rats, Panksepp and other scientists can figure out what’s going on in the brain during laughter. And it holds promise for human ills.

Northwestern biomedical engineering professor Jeffrey Burgdorf has found that laughter in rats produces an insulin-like growth factor chemical that acts as an antidepressant and anxietyreducer. He thinks the same thing probably happens in humans, too. This would give doctors a new chemical target in the brain in their effort to develop drugs that fight depression and anxiety in people. Even so, laughter itself hasn’t been proven to be the best medicine, experts said.

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Acidentes cardiovasculares estão entre as doenças que - UNIFESP 2010

Biologia - 2010Acidentes cardiovasculares estão entre as doenças que mais causam mortes no mundo. Há uma intricada relação de fatores, incluindo os hereditários e os ambientais, que se conjugam como fatores de riscos.

Leia o trecho do poema de Ruth do Carmo, extraído do - UNIFESP 2010

Língua Portuguesa - 2010Leia o trecho do poema de Ruth do Carmo, extraído do livro Sobre Vida.

Tio

Meu tio está velho

e não entende

o que se fala

(ouve menos)

mas está aqui,

ali, sentadinho,

sem camisa,

magro,

os pelos do peito

esbranquiçados.

O meu velho tio olha ao redor,

às vezes trocamos ideias

(tentamos).

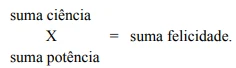

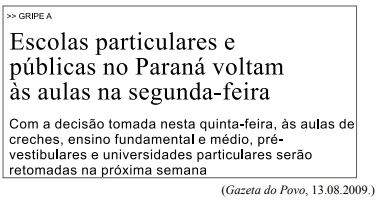

I. O advérbio já, indicativo de tempo, atribui à frase - UNIFESP 2010

Língua Portuguesa - 2010Considere a charge e as afirmações.

I. O advérbio já, indicativo de tempo, atribui à frase o sentido de mudança.

II. Entende-se pela frase da charge que a população de idosos atingiu um patamar inédito no país.

III. Observando a imagem, tem-se que a fila de velhinhos esperando um lugar no banco sugere o aumento de idosos no país.

O texto faz uma crítica ao a) uso inexpressivo de - UNIFESP 2010

Língua Portuguesa - 2010É fácil errar quando uma empresa ou seus dirigentes não têm clareza sobre o que de fato significam as bonitas palavras que estão em suas missões e valores ou em seus relatórios e peças de marketing. Infelizmente, não passa um dia sem vermos claros sintomas de confusão. O que dizer de uma empresa que mal começou a praticar coleta seletiva e já sai por aí se intitulando “sustentável”? Ou da que anuncia sua “responsabilidade social” divulgando em caros anúncios os trocados que doou a uma creche ou campanha de solidariedade? Na melhor das hipóteses, elas não entenderam o significado desses conceitos. Ou, se formos um pouco mais críticos, diremos tratar-se de oportunismo irresponsável, que não só prejudica a imagem da empresa mas – principalmente – mina a credibilidade de algo muito sério e importante. Banaliza conceitos vitais para a humanidade, reduzindo- os a expressões efêmeras, vazias.

(Guia Exame – Sustentabilidade, outubro de 2008.)

Considerando o ponto de vista do autor, a frase – O que - UNIFESP 2010

Língua Portuguesa - 2010É fácil errar quando uma empresa ou seus dirigentes não têm clareza sobre o que de fato significam as bonitas palavras que estão em suas missões e valores ou em seus relatórios e peças de marketing. Infelizmente, não passa um dia sem vermos claros sintomas de confusão. O que dizer de uma empresa que mal começou a praticar coleta seletiva e já sai por aí se intitulando “sustentável”? Ou da que anuncia sua “responsabilidade social” divulgando em caros anúncios os trocados que doou a uma creche ou campanha de solidariedade? Na melhor das hipóteses, elas não entenderam o significado desses conceitos. Ou, se formos um pouco mais críticos, diremos tratar-se de oportunismo irresponsável, que não só prejudica a imagem da empresa mas – principalmente – mina a credibilidade de algo muito sério e importante. Banaliza conceitos vitais para a humanidade, reduzindo- os a expressões efêmeras, vazias.

(Guia Exame – Sustentabilidade, outubro de 2008.)

No contexto, as palavras mina e efêmeras assumem - UNIFESP 2010

Língua Portuguesa - 2010É fácil errar quando uma empresa ou seus dirigentes não têm clareza sobre o que de fato significam as bonitas palavras que estão em suas missões e valores ou em seus relatórios e peças de marketing. Infelizmente, não passa um dia sem vermos claros sintomas de confusão. O que dizer de uma empresa que mal começou a praticar coleta seletiva e já sai por aí se intitulando “sustentável”? Ou da que anuncia sua “responsabilidade social” divulgando em caros anúncios os trocados que doou a uma creche ou campanha de solidariedade? Na melhor das hipóteses, elas não entenderam o significado desses conceitos. Ou, se formos um pouco mais críticos, diremos tratar-se de oportunismo irresponsável, que não só prejudica a imagem da empresa mas – principalmente – mina a credibilidade de algo muito sério e importante. Banaliza conceitos vitais para a humanidade, reduzindo- os a expressões efêmeras, vazias.

(Guia Exame – Sustentabilidade, outubro de 2008.)

Nas duas ocorrências, as aspas indicam que as expressõe - UNIFESP 2010

Língua Portuguesa - 2010É fácil errar quando uma empresa ou seus dirigentes não têm clareza sobre o que de fato significam as bonitas palavras que estão em suas missões e valores ou em seus relatórios e peças de marketing. Infelizmente, não passa um dia sem vermos claros sintomas de confusão. O que dizer de uma empresa que mal começou a praticar coleta seletiva e já sai por aí se intitulando “sustentável”? Ou da que anuncia sua “responsabilidade social” divulgando em caros anúncios os trocados que doou a uma creche ou campanha de solidariedade? Na melhor das hipóteses, elas não entenderam o significado desses conceitos. Ou, se formos um pouco mais críticos, diremos tratar-se de oportunismo irresponsável, que não só prejudica a imagem da empresa mas – principalmente – mina a credibilidade de algo muito sério e importante. Banaliza conceitos vitais para a humanidade, reduzindo- os a expressões efêmeras, vazias.

(Guia Exame – Sustentabilidade, outubro de 2008.)

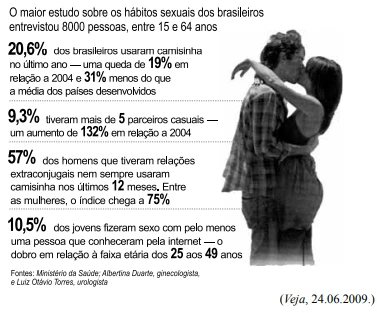

Conforme as informações apresentadas, um título - UNIFESP 2010

Língua Portuguesa - 2010Considere o texto.

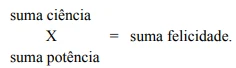

Conforme o pensamento de Jacinto, que ganhou a forma - UNIFESP 2010

Língua Portuguesa - 2010Jacinto e eu, José Fernandes, ambos nos encontramos e acamaradamos em Paris, nas escolas do Bairro Latino – para onde me mandara meu bom tio Afonso Fernandes Lorena de Noronha e Sande, quando aqueles malvados me riscaram da universidade por eu ter esborrachado, numa tarde de procissão, na Sofia, a cara sórdida do Dr. Pais Pita.

Ora nesse tempo Jacinto concebera uma ideia... Este príncipe concebera a ideia de que o homem só é “superiormente feliz quando é superiormente civilizado”. E por homem civilizado o meu camarada entendia aquele que, robustecendo a sua força pensante com todas as noções adquiridas desde Aristóteles, e multiplicando a potência corporal dos seus órgãos com todos os mecanismos inventados desde Teramenes, criador da roda, se torna um magnífico Adão quase onipotente, quase onisciente, e apto portanto a recolher dentro de uma sociedade e nos limites do progresso (tal como ele se comportava em 1875) todos os gozos e todos os proventos que resultam de saber e de poder... Pelo menos assim Jacinto formulava copiosamente a sua ideia, quando conversávamos de fins e destinos humanos, sorvendo bocks poeirentos, sob o toldo das cervejarias filosóficas, no Boulevard Saint-Michel.

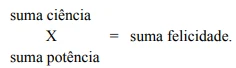

Este conceito de Jacinto impressionara os nossos camaradas de cenáculo, que tendo surgido para a vida intelectual, de 1866 a 1875, entre a Batalha de Sadowa e a Batalha de Sedan e ouvindo constantemente desde então, aos técnicos e aos filósofos, que fora a espingarda de agulha que vencera em Sadowa e fora o mestre-deescola quem vencera em Sedan, estavam largamente preparados a acreditar que a felicidade dos indivíduos, como a das nações, se realiza pelo ilimitado desenvolvimento da mecânica e da erudição. Um desses moços mesmo, o nosso inventivo Jorge Calande, reduzira a teoria de Jacinto, para lhe facilitar a circulação e lhe condensar o brilho, a uma forma algébrica:

Se a civilização era enaltecida por Jacinto, era de - UNIFESP 2010

Língua Portuguesa - 2010Jacinto e eu, José Fernandes, ambos nos encontramos e acamaradamos em Paris, nas escolas do Bairro Latino – para onde me mandara meu bom tio Afonso Fernandes Lorena de Noronha e Sande, quando aqueles malvados me riscaram da universidade por eu ter esborrachado, numa tarde de procissão, na Sofia, a cara sórdida do Dr. Pais Pita.

Ora nesse tempo Jacinto concebera uma ideia... Este príncipe concebera a ideia de que o homem só é “superiormente feliz quando é superiormente civilizado”. E por homem civilizado o meu camarada entendia aquele que, robustecendo a sua força pensante com todas as noções adquiridas desde Aristóteles, e multiplicando a potência corporal dos seus órgãos com todos os mecanismos inventados desde Teramenes, criador da roda, se torna um magnífico Adão quase onipotente, quase onisciente, e apto portanto a recolher dentro de uma sociedade e nos limites do progresso (tal como ele se comportava em 1875) todos os gozos e todos os proventos que resultam de saber e de poder... Pelo menos assim Jacinto formulava copiosamente a sua ideia, quando conversávamos de fins e destinos humanos, sorvendo bocks poeirentos, sob o toldo das cervejarias filosóficas, no Boulevard Saint-Michel.

Este conceito de Jacinto impressionara os nossos camaradas de cenáculo, que tendo surgido para a vida intelectual, de 1866 a 1875, entre a Batalha de Sadowa e a Batalha de Sedan e ouvindo constantemente desde então, aos técnicos e aos filósofos, que fora a espingarda de agulha que vencera em Sadowa e fora o mestre-deescola quem vencera em Sedan, estavam largamente preparados a acreditar que a felicidade dos indivíduos, como a das nações, se realiza pelo ilimitado desenvolvimento da mecânica e da erudição. Um desses moços mesmo, o nosso inventivo Jorge Calande, reduzira a teoria de Jacinto, para lhe facilitar a circulação e lhe condensar o brilho, a uma forma algébrica:

Considere as afirmações. I. O Realismo surge num - UNIFESP 2010

Língua Portuguesa - 2010Jacinto e eu, José Fernandes, ambos nos encontramos e acamaradamos em Paris, nas escolas do Bairro Latino – para onde me mandara meu bom tio Afonso Fernandes Lorena de Noronha e Sande, quando aqueles malvados me riscaram da universidade por eu ter esborrachado, numa tarde de procissão, na Sofia, a cara sórdida do Dr. Pais Pita.

Ora nesse tempo Jacinto concebera uma ideia... Este príncipe concebera a ideia de que o homem só é “superiormente feliz quando é superiormente civilizado”. E por homem civilizado o meu camarada entendia aquele que, robustecendo a sua força pensante com todas as noções adquiridas desde Aristóteles, e multiplicando a potência corporal dos seus órgãos com todos os mecanismos inventados desde Teramenes, criador da roda, se torna um magnífico Adão quase onipotente, quase onisciente, e apto portanto a recolher dentro de uma sociedade e nos limites do progresso (tal como ele se comportava em 1875) todos os gozos e todos os proventos que resultam de saber e de poder... Pelo menos assim Jacinto formulava copiosamente a sua ideia, quando conversávamos de fins e destinos humanos, sorvendo bocks poeirentos, sob o toldo das cervejarias filosóficas, no Boulevard Saint-Michel.

Este conceito de Jacinto impressionara os nossos camaradas de cenáculo, que tendo surgido para a vida intelectual, de 1866 a 1875, entre a Batalha de Sadowa e a Batalha de Sedan e ouvindo constantemente desde então, aos técnicos e aos filósofos, que fora a espingarda de agulha que vencera em Sadowa e fora o mestre-deescola quem vencera em Sedan, estavam largamente preparados a acreditar que a felicidade dos indivíduos, como a das nações, se realiza pelo ilimitado desenvolvimento da mecânica e da erudição. Um desses moços mesmo, o nosso inventivo Jorge Calande, reduzira a teoria de Jacinto, para lhe facilitar a circulação e lhe condensar o brilho, a uma forma algébrica:

Considere as afirmações.

I. O Realismo surge num momento de grande efervescência do cientificismo. No texto, isso se comprova pelas referências à vida intelectual e ao desenvolvimento da sociedade do século XIX.

II. Um personagem como Fabiano, de Vidas Secas, conforme descrito no trecho – Vermelho, queimado, tinha os olhos azuis, a barba e os cabelos ruivos; mas como vivia em terra alheia, cuidava de animais alheios, descobria-se, encolhia-se na presença dos brancos e julgava-se cabra. – seria infeliz na ótica de Jacinto, apresentada no texto.

III. Ora, como tudo cansa, esta monotonia acabou por exaurir-me também. Quis variar, e lembrou-me escrever um livro. Jurisprudência, filosofia e política acudiram-me, mas não me acudiram as forças necessárias. Essas palavras de Dom Casmurro, na obra homônima de Machado de Assis, assinalam uma personagem preocupada com o desenvolvimento da erudição, candidata à felicidade postulada por Jacinto.